1 Timothy 6

Slaves and Masters, Rich and Poor

Banksy

Steve Jobs, with later additions by unknown person, 15 February, 2016, Mural, 'The Jungle' refugee camp near the ferry port in Calais, France; PRISMA ARCHIVO / Alamy Stock Photo

‘Because Worthless’

Commentary by Eric C. Smith

Like the identity of the author of 1 Timothy, the identity of Banksy is disputed and contested. And like the literary corpus attributed to Paul, this work from Banksy is palimpsestuous, having been annotated and overwritten and reinscribed several times over. In its first iteration, it was an image of Steve Jobs, the late founder of Apple, carrying only a knapsack and an early Macintosh computer. Later artists added words to the original artwork. In large letters, ‘London Calling’ quoted the title of an album by British rock band The Clash—itself a quotation from BBC radio broadcasts during World War 2. Here, perhaps, it served as a reference to London as a particular centre of economic wealth and one of the preferred destinations of migrants. And, over the centre of the image, were scrawled the words ‘because worthless’.

This work appeared in 2015, as a humanitarian crisis consumed Europe. Refugees from North Africa, Syria, and elsewhere in the Middle East desperately made their way toward Europe, seeking both political and economic safety. In response, debates exploded across the continent, sometimes centring on economy, sometimes on national, religious, and ethnic identity, and sometimes on the threat of terrorism.

Banksy created this work on a wall in the Calais migrant camp in France, and the meaning seems straightforward. Pointing to Jobs’s own roots as the child of immigrants to the United States, the artist is making the common observation that immigrants contribute much more to our societies than they require in resources. After all, there is a good chance that the device you are reading this on owes something to this son of migrants.

But the ‘because worthless’ of a later anonymous artist provokes a question: what is worth, and where does it come from? The implication of an image of Steve Jobs as a refugee is that refugees’ worth is tied to their utility as economic subjects and objects. Immigration fuels growth, and innovation comes from the mixing of a diversity of cultures. No prophet of postliberalism could disagree. But the later addition, ‘because worthless’, complicates things.

Likewise, this part of 1 Timothy is complicated, and even confused, about what makes human beings worth something. Is it being a docile and obedient slave? Is it contentment with one’s lot in life? Or a life of devotion to God?

References

Ellis-Peterson, Hannah. 2015. ‘Banksy Uses Steve Jobs Artwork to Highlight Refugee Crisis, 11 December 2015’, www.theguardian.com, [accessed 20 June 2019]

Ibrahim, Yasmin, and Anita Howarth. 2018. Calais and its Border Politics: From Control to Demolition (Abingdon and New York: Routledge)

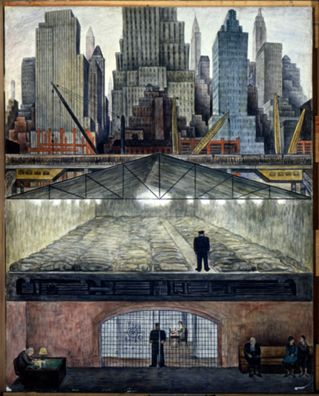

Diego Rivera

Frozen Assets, 1931–32, Fresco on reinforced cement in a galvanized-steel framework, 239 x 188.5 cm, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico; Credit: © 2019 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Schalkwijk / Art Resource, NY

‘The Root of All Kinds of Evil’

Commentary by Eric C. Smith

Diego Rivera arrived in New York as the Great Depression lengthened and deepened, and what he encountered there informed and inflamed the leftist political leanings he had already developed in his native Mexico. In this mural, painted during his time in the city, Rivera captures and comments upon the instrumentalization of humanity, as the grandeur and built environment of the city is undergirded by the suffering of its inhabitants—suffering which itself rests on a bank vault, guarded and minded by the beneficiaries of capitalism.

As is common in the later writings of the New Testament, this part of 1 Timothy is keen to offer advice for the living of life. Especially prominent here is a warning against wealth and the desire for it, both as a personal principle (it plunges people into ruin and destruction) and as a force that works on an almost-cosmic scale (it is the root of all kinds of evil). Framed as advice to a young believer, from a beloved pastor–mentor to a protégé in the faith, the warning is clear: wealth has sundered many from their faith.

While Rivera’s painting is oriented vertically, with one scene atop another, it editorializes the horizontal—the relationships between persons, which are conditioned and severed by the vertical disparities of wealth. At the top, the city rises with its skyscrapers, and cranes imply that more are on the way. But in that urban landscape there are no persons; only in the bottom two-thirds of the image do we find any human beings, and they are diminutive ones.

In the middle register, in a scene that almost evokes a morgue, the anonymous sleeping bodies of the homeless are packed into a shelter as a policeman looks on. And at the bottom, the bankers and their customers are the only people with faces. Their features are indistinct, but they exude calm and self-satisfaction.

1 Timothy’s warning is more intelligible to the masses in the middle frame than it is to the wealthy at the bottom, but Rivera puts the root beneath the ground just as the epistle does—the root of evil sending up both the triumph of the city and the misery of its labourers.

References

Dickerman, Leah, Diego Rivera, and Anna Indych-López. 2011. Diego Rivera: Murals for the Museum of Modern Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art)

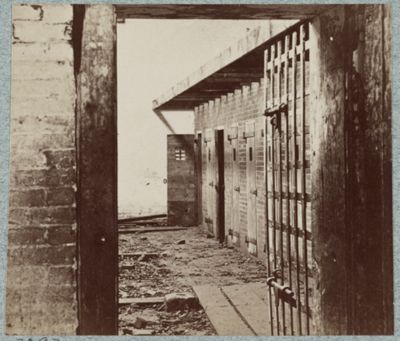

Unknown artist

Slave pen, Alexandria, Virgina, Taken 1861–65; printed 1880–89, Photograph, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC; Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C., LC-DIG-ppmsca-34798

The Pen is Mighty

Commentary by Eric C. Smith

Few parts of the Bible have had direr consequences in human suffering than the ones that urge enslaved persons to respect and obey their masters. The costs of these verses are on display in this photograph from the period of the American Civil War, taken near the capital city of Washington. This image is haunted by the shades of Scripture in the practice of chattel slavery, and with the protests of enslaved persons who bore the weight of biblical interpretation that fastened them in chains.

In her old age, Nancy Ambrose, grandmother of theologian and philosopher Howard Thurman, refused to hear any writings attributed to the apostle Paul, because of passages like 1 Timothy 6:1–2 (Thurman 1949: 30). She had been enslaved as a girl on a plantation in Florida, and had heard the preachers brought in by the slaveholder to preach biblical obedience to earthly masters. It is not difficult to imagine similar voices interpreting Scripture in this ‘slave pen’, where biblical discourses of captivity and servitude would have been whispered by captives and proclaimed by captors.

Pictures from the early days of photography, like this one, often receive attention for their documentary quality. But even as this image documents, it also functions as art that troubles and vexes the viewer’s perspective, and provokes pathos. This image is a profound commentary on and indictment of the practice of slavery, obliterating any myths about happy slaves or kindly masters. An iron-barred and double-latched door frames an inner yard, where more doors lead to cells where enslaved persons were kept. The most meagre of windows provide the only access to the world outside.

The photograph also evokes other spaces of subjection and violence, authorized and undergirded by biblical interpretation: the Inquisition, the colonial barracks, the Middle Passage, the concentration camp, the prison. It reminds us that not all readings of the Bible are life-giving, and indeed many come at great human cost.

References

Powery, Emerson B., and Rodney S. Sadler. 2016. The Genesis of Liberation: Biblical Interpretation in the Antebellum Narratives of the Enslaved (Louisville: Westminster John Knox)

Thurman, Howard. 1949. Jesus and the Disinherited (Nashville: Abingdon-Cokesbury)

Banksy :

Steve Jobs, with later additions by unknown person, 15 February, 2016 , Mural

Diego Rivera :

Frozen Assets, 1931–32 , Fresco on reinforced cement in a galvanized-steel framework

Unknown artist :

Slave pen, Alexandria, Virgina, Taken 1861–65; printed 1880–89 , Photograph

Human Worth and Dignity

Comparative commentary by Eric C. Smith

1 Timothy 6:1–21 is a work of exhortation. At the close of the letter, the author is offering up wisdom for living—some of it practical, some of it spiritual, and some of it both. The conceit of the letter and therefore this chapter is that it is advice to young Timothy, the protégé and the fellow worker of Paul. But the wisdom offered here is not only to Timothy, but to the reader also, who stands in for the faithful at large, whom the author also imagines as an audience for the letter. This is personal exhortation, but it is also a general one.

It is striking then that the author lingers so long on advice about the economic life of human beings. There are other pieces here too—a standard Pauline virtue list makes its appearance (see v.11), as in Galatians 5:16–26, Ephesians 5:1–10, 1 Thessalonians 5:12–22, and Romans 12:9–21; 13:8–14, among others—but the centre of this discourse is the value of human life as reflected and refracted through economy and social constructions. The Pastoral Epistles are known as reservoirs of conservative theology and ecclesiology, working to push the Pauline tradition toward acceptability and sustainability as the movement spread into the broader Roman world. But here at the end of 1 Timothy we find these conservative, stabilizing sentiments alongside ones that would be at home in much more revolutionary settings.

Scholars debate the demographics of earliest Christianity. Was it a movement of the lowest classes, slaves, and women, or did it comprise a much broader cross-section of the Roman world? Did its adherents practice a form of socialized life, or was the church an extension of normative Roman patronage systems, with wealthier and higher-class members underwriting the life of the community in an expression of the honour/shame system? There is enough in this chapter of 1 Timothy to support several different possibilities. Admonitions to social order (slaves should regard their masters with honour) and a rejection of wealth co-exist here, and it seems that the author of 1 Timothy expected to have readers and hearers from multiple locations on the social landscape.

In this regard, 1 Timothy is like Diego Rivera’s Frozen Assets, which sees the city in multiple ways at once. Rivera’s mural takes account of the soaring skyscrapers and the titans of finance that they imply, but it also focuses on the experience of the homeless poor, who are packed into a shelter like sardines into a can. The author of 1 Timothy understood that the audience of the letter would be reading or hearing it from a number of different perspectives.

Perspective also matters in the photograph of the ‘slave pen’ from Alexandria. While it is a sympathetic image that provokes solidarity with and compassion for the persons enslaved and confined there, the view is from the outside—from freedom—looking inward. This might be something like the view of the community from the perspective of ‘those who in the present age are rich’ in 1 Timothy 6:17–19. If it is true that they are patrons of the gathered Jesus-followers, then the author of the letter might be urging them toward more solidarity with the poor and dispossessed among them.

The overwritten, annotated, and reworked work of Banksy in Calais might be our best analogue for what we find in 1 Timothy 6. It is a commentary on status, wealth, inclusion, and difference, but it is a multidirectional one, with indistinct authorship and overlapping messages. It gestures at the inherent worth of persons even as it links that worth to economic value, and appeals to the possibility of wealth as an argument for human dignity. Like 1 Timothy 6, the Banksy in Calais speaks across class and status toward multiple locations, and like 1 Timothy, the image leaves us with as many questions as answers.

References

Dickerman, Leah, Diego Rivera, and Anna Indych-López. 2011. Diego Rivera: Murals for the Museum of Modern Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art)

Ibrahim, Yasmin, and Anita Howarth. 2018. Calais and its Border Politics: From Control to Demolition (Abingdon and New York: Routledge)

Longenecker, Bruce W. 2010. Remember the Poor: Paul, Poverty, and the Greco-Roman World (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans)

Commentaries by Eric C. Smith