John 15:1–17

Subversive Horticulture

Works of art by Giuseppe Arcimboldi, John W. Mills, The British Army Film and Photographic Unit and Unknown Greek school

Unknown Greek school

Christ the True Vine icon, 16th century, Egg tempera on panel; Byzantine Museum, Athens, Greece / G. Dagli Orti / De Agostini Picture Library / Bridgeman Images

Cultivation

Commentary by Stephen M. Garrett

The renowned fifteenth-century Cretan iconographer Angelos Akotantos (d.1450) painted the icon Christ the Vine during a pivotal and turbulent period of the Church’s history. The collapse of the Byzantine Empire was imminent, leading to a contentious Church council in the cities of Ferrara and Florence (c.1438–45) where leaders strove to unify the Eastern and Western Church. Today, the icon is sequestered in a Cretan monastery; but, like all icons, many versions exist, including this one in the Byzantine Museum in Athens (Mantas 2003: 355–56).

The large figure of Christ with extended arms is seated at the nexus of the intertwined branches, establishing him as the common root and life of the Church (John 15:1–8). An open book, inscribed with excerpts from John 15, is superimposed on the Christ figure at the centre of the icon, suggesting the Word’s centrality. St Peter and St Paul, perhaps representing the two branches of the Church, East and West (Vassilaki 2013–14: 115), are prominently positioned on either side of Christ. They are seated higher than the other apostles while the evangelists sit to Christ’s immediate left and right, dialoguing in pairs. The remaining apostles, like Christ, hold open books and scrolls—their eyes fixed on him. The hanging fruit symbolizes the continuation of the faithful: as they abide in Christ so too he abides in them (John 15:4).

These direct, visual references to unity are built upon an indirect reference to another well-known type of image, The Tree of Jesse (twelfth century onwards). The latter depicts the lineage of Christ: it begins with King David’s father, Jesse, as its root (Isaiah 11:1); various prophets are its branches; and Mary and the Christ child appear at its centre. Such references to the Jesse Tree in the icon of Christ the Vine subtly suggest further layers of unity—not only between the branches of the divided Church, but also between the Church and Israel and thus between the Testaments, for it is as the ‘true vine’ of Israel (John 15:1) that Christ brings life to the Church (John 15:5).

This larger continuity between the Testaments makes a further claim on the Eastern and Western Church to remain united in obedience to Christ (John 15:9–10). ‘Love is the fulfilling of the law’ (Romans 13:10). Jesus shows what sacrifice such love must entail, for ‘greater love has no man than [that he] lay down his life for his friends’ (John 15:13). East and West, like Jesus’s first disciples, must love one another in a sacrificial existence if they are to be true branches of the true vine (John 15:12, 17).

References

Mantas, Apostolos G. 2003. ‘The Iconographic Subject “Christ the Vine” in Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Art’, Τόμος ΚΔ': 347–60

Vassilaki, Maria. 2013–14. ‘Cretan Icon-Painting and the Council of Ferrara/Florence (1438/39)’, ΜΟΥΣΕΙΟ ΜΠΕΝΑΚΗ: 115–28

Giuseppe Arcimboldo

Vertumnus, 1591, Oil on panel, 70 x 58 cm, Skoklosters Slott, Sweden; 11615, Photo: Skokloster Castle, Sweden / Bridgeman Images

Restoration

Commentary by Stephen M. Garrett

Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1527–93) was an Italian Renaissance painter well-known for an innovative and imaginative style that incorporated a variety of objects like fruits, vegetables, flowers, fish, and books. He is often heralded as the inspiration behind the twentieth-century avant-garde movement, Surrealism.

Vertumnus is named after the Roman god of the seasons—a god of metamorphoses and change—and is a portrait of the Habsburg emperor, Rudolf II. The painting seems absurd and playful in its grotesquery. But it may be trying to capture something more, as though telling a ‘serious joke’ (Kaufmann 2010: 199), for it is a reflection on the political situation of the Habsburg Empire at the time when it was painted. This exquisite cornucopia foretells a coming ‘golden age’ that is flush with plenitude. When we realize how the Habsburgs’ influence was expanding—evidenced here by the exotic renderings of fruits, flowers, and vegetables unattainable in continental Europe—we realize that this imperial portrait is no merely amusing fancy.

Arcimboldo’s Vertumnus brings into relief the metamorphosis Jesus’s followers will endure as the Gardener prunes and burns the branches that do not bear fruit (John 15:2–6). This process of change is intended to restore (John 15:3) and produce more fruit by the Spirit such that the Gardener is honoured and glorified (John 15:6–8).

What is this fruit? Why does it glorify the Father? Might its manifestation in the Christian life initially appear absurd (perhaps monstrous), while harbouring a deeper meaning and beauty that is disclosed to the discerning?

Jesus identifies this fruit as love, a love born counterintuitively through obedience and sacrifice. In the deeds of the disciples, this love glorifies the Father because it conforms to Jesus’s own love (John 15:9–12).

The manifestation of this fruit in the lives and faces of Jesus’s disciples is not merely for their benefit (John 15:11); rather, it is to be extended into and shared with the world. It is evidence of God’s Kingdom in the present and its future coming (John 15:15–17), where there will be plenitude, flourishing, and abundance—a true ‘golden age’ (Revelation 21–22).

References

Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta. 2010. Arcimboldo: Visual Jokes, Natural History, and Still-Life Painting (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

Tucker, Abigail. 2011. ‘Arcimboldo’s Feast for the Eyes, January 2011’, www.Smithsonianmag.com, [accessed 18 June 2019]

John W. Mills and the British Army Film and Photographic Unit

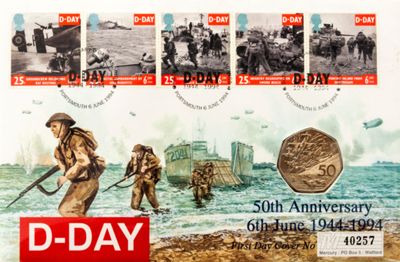

Great Britain 50p D-Day Coin First Day Cover (6th June 1994) to commemorate the Fiftieth Anniversary of D-Day, 1994, Coin, Stamps; Marc Tielemans / Alamy Stock Photo

Propagation

Commentary by Stephen M. Garrett

Award winning English sculptor John W. Mills, dubbed the ‘Sculptor to the Nation’ (Smith 2019), was commissioned by the Royal Mint in 1993 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the largest amphibious assault in history. In the wee hours of 6 June 1944, the seas and skies teemed with ships, landing crafts, planes, and over 150,000 soldiers who stormed the beaches of Normandy as part of Operation Overlord. Mills’s vivid recollection of that historic day as an impressionable young boy inspired his design of a coin to memorialize those who sought to liberate German occupied France and eventually all of Europe.

The commemorative, uncirculated coin is packaged in a ‘First Day Cover’, an envelope illustrated with a watercolour print depicting British soldiers landing on the beaches of Normandy. The Cover also has five stamps, postmarked with a date exactly fifty years to the day after D-Day. They capture scenes from that fateful day filmed by the Army Film and Photographic Unit and record, in sequence, the pre-dawn preparations, the heroic landings, and the gallant advance inland that would eventually liberate occupied France.

Perhaps memorializing such brave actions in this manner seems inappropriate as Allied soldiers lost much that day, whether their lives or their innocence, that cannot, like mass-produced coins and stamps, have a price put on them. Nevertheless, the uncirculated coins, the five post-marked stamps, and their First Day Covers commemorate the shared sacrifice of the fallen, denoting the love evident in ‘laying down one’s life for another’ (John 15:13).

The Church has often made glib, trite, and impertinent associations between its sense of sacrifice and the sacrifice of soldiers for country, sometimes losing sight of the means by and the ends for which Christ’s sacrifice was made (John 15:9–13). This conflation has led to attempts to advance the Kingdom of God, even today, by the sword, despite Jesus’s refusal to be identified as a militaristic Messiah (John 10:10).

As these commemorative coins ‘abide’ in their First Day Covers in uncirculated, mint condition, they seem to point forward as well as backward; not only honouring a memory, but also expressing longing for a day when there will be no more death, no more pain, or suffering (Revelation 21:4).

It is this Kingdom that is propagated in the present by the Spirit as the sent disciples ‘abide’ in Christ (John 15:5) while they also go and bear fruit, ‘fruit that will last’ (John 15:16).

References

Hastings, Max. 1984. Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy (New York: Simon & Schuster)

Smith, Chris Frazer. 2019. ‘Sculptor to the Nation’, ICAS Art Magazine, January–March 2019: 29–33

Unknown Greek school :

Christ the True Vine icon, 16th century , Egg tempera on panel

Giuseppe Arcimboldo :

Vertumnus, 1591 , Oil on panel

John W. Mills and the British Army Film and Photographic Unit :

Great Britain 50p D-Day Coin First Day Cover (6th June 1994) to commemorate the Fiftieth Anniversary of D-Day, 1994 , Coin, Stamps

The Radicality of Life in Christ

Comparative commentary by Stephen M. Garrett

Jesus’s declaration that he is the true vine opens an extended horticultural metaphor (John 15:1) that elucidates the subversive fruitfulness of persisting in Christ as his disciples carry forth his mission by the Spirit to the world.

God the Father, as the ‘Gardener’, cultivates the vine. Meanwhile its branches bear fruit, not of their own accord but in Christ by the Spirit.

As the true vine, Jesus seems implicitly to contrast and connect himself with Old Testament vine imagery, which signifies Israel’s faithlessness to YHWH (e.g. Psalm 80:8–16; Isaiah 5:1–7; Jeremiah 2:21; Ezekiel 15:1–8). This contrast, according to John’s Gospel, does not belie Christianity’s Jewish heritage but rather reveals the apostasy of those Jews who rejected Jesus as the Messiah (John 1:47–50; 8:31–59; 19:21). Christ the vine, then, connects Jesus as the truth of Israel and the life of the world.

Christ the Vine seems to capture both the vine imagery in John 15 and the Tree of Jesse tradition with its Old Testament associations. It’s the fact that Christ the Vine has achieved the form of an icon, though, that presses western understandings of this passage to go further than they might otherwise do.

Icons, based on the incarnation and transfiguration of Christ (Ouspensky and Lossky, 1999: 23–50), function as ‘windows into heaven’—a physical means by which to glimpse the glory of the eternal. Icons, in their simplicity, are not designed to stir the emotions but rather to redirect them toward the prayerful contemplation of God in service of spiritual communion. As such, Christ the Vine underscores the animate reality of the abiding into which Jesus’s disciples are called. Creaturely life is intertwined with the radicality (radix) of the resurrected Christ by the Spirit. Such life continues in the present world, yet is not of it (John 17:14–15).

Union and communion with the living Christ through prayer and obedience yield fruit to the joy, pleasure, and glory of God the Father. The bearing of fruit is an ongoing, dynamic process. This horticultural imagery of flourishing and abundance is vividly captured in Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s Vertumnus. The way in which Arcimboldo honours Rudolf II seems counterintuitive as he employs the absurd and subverts the norms of sixteenth-century portraiture. There is nevertheless a peculiar beauty to Vertumnus. Might the fruit of the Christian life and the beauty it portrays be counterintuitive, absurd, and even subversive of contemporary socio-cultural expectations? Might the radicality of life in Christ be strange, even foolish (1 Corinthians 1:18) as God’s power is perfected in weakness (2 Corinthians 12:8–10), while still being mysteriously attractive and relatable to shared human experience.

Jesus’s parting words and actions do seem counterintuitive as—in the broader context of John 15—he washes the disciples’ feet (John 13:1–17), assures them of his presence by the Spirit even after his departure (John 14:15–21), and imparts a peace (shalom) that is not of this world (John 14:27–29). Not only do these actions make no sense to the disciples, Jesus explains how the world will also reject and persecute them for the apparent irrationality of their faithful obedience to him. The fruit they will bear by the Spirit as they abide in him, and love ‘the other’ sacrificially (John 15:18–16:11), will appear absurd. Such abiding may get them killed (John 16:1–2). The fruit they bear, nevertheless, will subvert the powers and principalities of this world as Jesus has condemned and defeated ‘the ruler of this world’ in the dawning of the Kingdom (John 16:11, 33). As they share in his gifts, they will manifest a strangely attractive joy (John 15:11; 16:19–24).

Stamps made to be ‘sent’ and coins made to be ‘spent’ may seem useful illustrations of the missional aspects of the Kingdom of God in Jesus’s farewell discourse. Jesus calls his disciples to participate in this sobering mission (John 14:31) and then commissions them in the power of the Spirit (John 15:16) to fulfil their purpose by propagating the fruit of the Christian life in the world (John 15:16–17).

But the Fiftieth Anniversary of D-Day First Day Cover offers us another perspective. Its contents may appear to occupy a suspended middle of unrealized purpose: a coin that has not been spent and stamps that have never been sent (even as those whom they commemorate have).

But perhaps the uncirculated, mint-condition coin and the postmarked stamps fulfil a different purpose: ‘sending a message’ in a different way; a ‘sending’ which is at the same time an ‘abiding’. The sending of disciples by Christ, who is himself sent by the Father, is categorically different from the sending of soldiers to war. The radicality of the Christian life will be costly—requiring sacrifice (John 16:1–4)—but never futile. There is hope for those who ‘abide’ in Christ even amidst pain, suffering, and loss. They shall live, even as he lives as the resurrected One, eternally ‘sent’ by the Father and never expended.

References

Ouspensky, Leonid and Vladimir Lossky. 1999. The Meaning of Icons, trans. by G.E.H. Palmer and E. KadlouBovsky (New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press)

Commentaries by Stephen M. Garrett