Isaiah 11:1–10

War and Peace

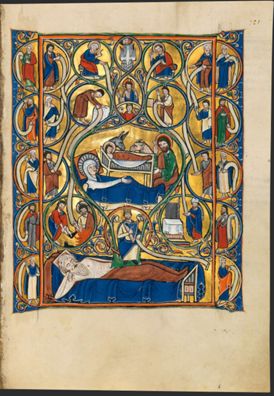

Unknown English artist

Tree of Jesse, from an English Psalter in Latin, 1190–1210, Illuminated manuscript, 27.7 x 19.3 cm, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich; BSB Clm 835, fol. 121r, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich

Roots and Branches

Commentary by Peter S. Hawkins

Early on, Christians found ways to ‘discover’ Jesus in the Hebrew Bible. The genealogies found in Matthew and Luke recall the ‘begat’ passages in Genesis and link Jesus to his Old Testament ancestors. Matthew (1:1–17) traces a line from Abraham, and Luke’s line (3:23–38) goes all the way back to Adam. For Luke, Jesus is also ‘son of David, the son of Jesse’ (vv.31–32).

In the Middle Ages, the prophecy of Isaiah 11, with its mention of Jesse as the stump and root of a Davidic lineage, took visual form as a royal family tree. It shows Jesus as the fulfilment of a messianic inheritance ‘rooted’ in the Old Testament and made manifest in a proliferation of medieval ‘Jesse trees’ produced in various media. In this early thirteenth-century manuscript illumination from Germany, we see Jesse, bottom centre, as the source from whom all genealogical blessings flow. The largest figure in the composition, he lies recumbent, eyes closed, suggesting sleep, a visionary state, or even death. From his groin extends a ‘shoot’ that supports David the Psalmist and then divides, becoming a branch that winds its way upward through history.

At the centre of the composition, the Virgin Mary mirrors the posture of Jesse within a manger tableau that shows the infant Son of God blessed by the earthly Joseph. Above the Holy Family appear the four Evangelists clustered around an image of the full-grown Christ. At the apex of the composition the Holy Spirit descends from the Father (a face in the heavens) in the form of a dove bearing seven tongues of flame. No doubt a representation of the seven spiritual gifts (traditionally identified on the basis of Isaiah 11:3 as wisdom, understanding, counsel, strength, knowledge, piety, fear of the Lord), they will come to rest on the ‘shoot’ who has sprung from Jesse’s tree (Isaiah 11:1–2).

From the minimal reference to this shoot in Isaiah’s prophecy, the artist works within an established Christian tradition to display a profusion of figures and a complex backstory—a richly fruitful, Testament-spanning family tree.

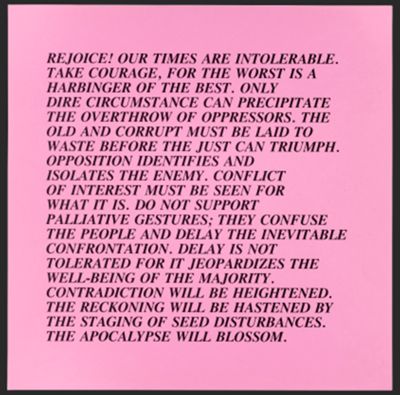

Jenny Holzer

Untitled (Rejoice!), from 'Inflammatory Essays', 1979–82, Offset lithograph in black on pink wove paper, 542 x 542 mm, The Art Institute of Chicago; Gift of David C. and Sarajean Ruttenberg, 1998.914.8, © Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY

The Rod of His Mouth

Commentary by Peter S. Hawkins

The descendant of Jesse foretold by Isaiah will be known, along with his other attributes, for the sheer force of his speech: in dealing justice, ‘he shall smite the earth with the rod of his mouth’ (Isaiah 11:4). This phrase also embeds itself in the book of Revelation, whose rebirth and interweaving of Hebrew Bible imagery brings messianic prophecies into New Testament fulfilment. In Revelation, the rod sprouts with a vengeance. Now it is the messianic warlord Christ who wields a rod of iron (Revelation 2:27; 12:5; 19:15); and a ‘sharp two-edged sword’ (Revelation 1:16), ‘with which to smite the nations’ (19:15; c.f. Isaiah 63 and Wisdom 18). The rod that grows up from Jesse’s stump, and that flowers initially in David, becomes manifest at the end of time in Jesus, the ‘root of David’ (Revelation 5:5; 22:16). With destruction issuing from his mouth, ‘the name by which he is called is The Word of God’ (19:13).

Medieval renderings of the ‘rod of his mouth’ are frequently quite literal—a sharpened blade issues from Christ’s mouth, as speech takes the form of his ‘terrible swift sword’ (to recall the ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic’). A very different way to imagine speech of such force can be found in Jenny Holzer’s ‘Inflammatory Essays’ of 1977–82, a series of over 100 mini-treatises printed on throw-away vari-coloured neon paper.

Her project began as posters put up, randomly and anonymously, around New York. Consisting only of text (100 words divided into 20 lines), Holzer’s italicized, upper case words give voice variously to Emma Goldman, Mao Zedong, Valerie Solanis, Karl Marx, and others—all without attribution. The effect is a visual rant that conjures up something ‘between a batty dictator, a leftist activist and a sage prophet’ (Frank 2017). The messages in this example range from ‘REJOICE! OUR TIMES ARE INTOLERABLE’ to ‘THE APOCALYPSE WILL BLOSSOM’. It is impossible in Holzer’s ‘Essays’ to identify a single speaker or a consistent point of view. Nonetheless, the rod of someone’s mouth forces us to pay attention, whether to affirm or reject the proclamations. Interpretation rather than obedience is all.

References

Frank, Priscilla. 2017. ‘Jenny Holzer’s ‘Nasty’ Essays Will Get You Ready For A Revolution, 24 January 2017’, www.huffingtonpost.com, [accessed 11 July 2018]

Edward Hicks

The Peaceable Kingdom, c.1833, Oil on canvas, 44.5 x 60.2 cm, Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts; Museum purchase, 1934.65, Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, USA / Bridgeman Images

The Peaceable Kingdom

Commentary by Peter S. Hawkins

The Peaceable Kingdom is a title Edward Hicks (1780–1849) gave to over sixty painted renderings of Isaiah 11, a text he would contemplate for more than thirty years (Weekley 1999; Jones 2016).

This particular painting offers a visual exegesis of the Scripture. It shows a day yet to come when the world is restored to primeval innocence, when ‘natural’ enemies dwell together in peace (for a sense of the conflicts concealed within Hicks’s later ‘Kingdoms’, see Cotter 2000). Here, as forecast in Isaiah’s prophecy, predatory lions do not menace their customary prey (11:6), carnivorous bears graze alongside cattle (v.7), a little child is wondrously raised to prominence (v.6), even as a pair of youngsters ‘play over the hole of the asp’ (v.8) and pat a leopard’s extended paw. The style of the painting, its playfulness and apparent naivety, suggests an unfallen Eden projected into a new Golden Age.

Hick’s vision is not ahistorical, however. He juxtaposes a world where ‘natural’ enemies become friends with an actual historical moment of peace-making between former antagonists. In the left background, we see William Penn—a Quaker, like Hicks—negotiating an accord between white colonists and the native American population. This event became the subject of five paintings made by Hicks from 1850–5. All of them depict the 1681 treaty struck between William Penn and the Leni-Lenape tribe.

The inclusion of this scene in the composition suggests that Isaiah’s prophecy can be realized in historical time if only occasionally, as it was once through the intervention of a peacemaker like Penn. For something more universally enduring, however, what Isaiah speaks of as ‘the spirit of the Lord’ (11:2) must be shed abroad so that all the world becomes Zion’s holy mountain. For Quakers, that meant the shining of the ‘inward Light’ within humanity. Only with its radiance would the earth ‘be full of the knowledge of the Lord as the waters cover the sea’ (v.9).

References

Cotter, Holland. 2000. ‘Art Review: Finding Endless Conflict Hidden in a Peaceable Kingdom, 16 June 2000’, www.nytimes.com, [accessed 26 April 2018]

Jones, Victoria Emily. 2016. ‘The Peaceable Kingdoms of Edward Hicks’, Art & Theology, available at https://artandtheology.org/2016/12/06/the-peaceable-kingdoms-of-edward-… [accessed 30 October 2018]

Weekley, Carolyn J., with Laura Pass Barry. 1999. The Kingdoms of Edward Hicks (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

Unknown English artist :

Tree of Jesse, from an English Psalter in Latin, 1190–1210 , Illuminated manuscript

Jenny Holzer :

Untitled (Rejoice!), from 'Inflammatory Essays', 1979–82 , Offset lithograph in black on pink wove paper

Edward Hicks :

The Peaceable Kingdom, c.1833 , Oil on canvas

The Apocalypse Will Blossom

Comparative commentary by Peter S. Hawkins

In chapter 11, Isaiah addresses his prophecy to an anxious people and offers them hope. They may currently be like a felled tree, a mere stump, but from their loss will come, in the Lord’s own time, renewal—a shoot, a branch, a leader, an earth transformed into a holy Mount Zion.

The dating of this text is uncertain. It may be as early as the eighth century BCE or as late as the post-exilic period. The anxiety it attempts to assuage is a factor in any case.

Edward Hicks takes Isaiah’s text to heart, returning to it again and again in the first half of the nineteenth century as he imagines the mountain of the Lord as a new American Eden. Animals (and the otherwise fractious people they may represent) live among one another in peace. A ‘little child’, presides, and in the foreground we see both the nursing and the weaned children of Isaiah 11:8. Isaiah’s emphasis, however, is on an adult offshoot of Jesse, one who has the spirit of the Lord within him, who is able to serve as God’s regent not only by the exercise of wisdom, righteousness, and faithfulness, but by the proper exercise of power. The poor will be raised up and judged fairly, the wicked will be ‘put down’. A fulfilment of that prophecy is suggested by the inserted scene of William Penn making peace with Native Americans, not by fiat but by mutual agreement—a Quaker consensus or ‘sense of the meeting’.

In the anonymous medieval ‘stump of Jesse’ illumination we see that the Davidic lineage has long been ‘sprouting’ in obedience to the initial divine command to ‘be fruitful and multiply’ (Genesis 1:28; 9:7). From Jesse, there issues a patriarchal forest of witnesses. The tree’s curling branches showcase David’s son Solomon, the Temple Builder, and Moses called to action by the Burning Bush. But if Jesse is the father of the line, Mary’s motherhood brings it to full flowering. Indeed in Jesse's visual ‘rhyming’ with Mary, we might be prompted to discern two nativity scenes here and not just one: the Old Testament birthing the New. And we see it is not always blood that unites those in this lineage; they include the Evangelists, brought in by providence not birth.

Hicks’s Peaceable Kingdom looks forward—anticipating an abiding peace. The Jesse Tree looks backward—tracking a descent from an ancient ancestor and an ascent to the birth of Christ. The conceptual artist Jenny Holzer’s work focusses on the ambiguous precarity of the present.

Renowned for text-based works that are projected as images onto stable architecture (buildings, billboards, marquees, urban landscapes), Holzer’s messages are typically ephemeral: they endure only as long as does the projection. The words she uses, often not her own, confront, even assault the viewer, like the biblical ‘handwriting on the wall’ that spoke truth to power at Belshazzar’s Feast: ‘You have been weighed in the balances and found wanting’ (Daniel 5:24–28). Her messages, however, are mixed, more provocative than prophetic. They come from far and wide; they do not constitute a consistent or singular Word of the Lord.

Holzer’s ‘voice’, through the ventriloquization of multiple other voices, is at full force in her ‘Inflammatory Essays’ from the late 1970s—short, mass-produced texts that pull no punches and take no prisoners. The rod of her mouth is sharp even on throwaway paper. When the works were first made, one would have looked in vain for the sources of the words she presents in italicized upper case, even if today Google searches might help identify the famous and the infamous. Although she speaks as one who has authority, she does not channel any ‘Word of the Lord’ or invoke a Higher Power. If anything, the ‘essay’ given here echoes left wing agitprop and Marxist ‘gospel’: ‘DO NOT SUPPORT/ PALLIATIVE GESTURES; THEY CONFUSE/ THE PEOPLE AND DELAY THE INEVITABLE/ CONFRONTATION’. Nonetheless, Holzer replicates the prophet’s alternating mixture of weal and woe. ‘OUR TIMES ARE INTOLERABLE’, but ‘THE WORST IS A HARBINGER OF THE BEST’.

Isaiah’s prophecy comforts an anxious Israel with hope for restoration; the Jesse Tree presents Jesus’s genealogy as the providential fulfilment of ancient expectation; Hicks’s painting depicts a realized eschatology in a corner of Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, Holzer reinvents the voice of the prophet, so that forceful speech is exposed as a weapon of destruction as well as of ‘wisdom and understanding’ (Isaiah 11:2). But hope prevails, as it does in Isaiah: ‘THE APOCALYPSE WILL BLOSSOM’ gets the essay’s last word.

Commentaries by Peter S. Hawkins