Isaiah 63:1–14

The Winepress

Caspar ?

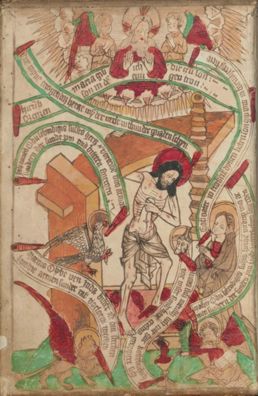

Christ in the Winepress (The Mystical Winepress), in Breviarium Romanum by Jakob Wolff (Basel c.1493), print pasted in front mirror, 1460–70, Woodcut, 388 x 257 mm (sheet), Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich; MS Rar. 327, vol. 1 BOD-Ink B-897 - GW 5165, Courtesy of Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich

The Crimson Garments

Commentary by Angela Russell Christman

Single-sheet prints were first produced from woodblocks in the early 1400s. Many of those that were made as individual artworks do not survive, and those in good condition were often preserved because they were pasted inside books. This woodcut print was glued to the inside front cover of a fifteenth-century breviary from a Franciscan monastery in the Bavarian city of Ingolstadt.

By the second century Christians began to interpret the ‘crimsoned garments’ of Isaiah 63:1–3 (cf. Revelation 19:11–16) as a prophecy of Christ’s blood-stained body. Christ treads the winepress during his Passion, producing the Eucharistic cup. This reading took deep root in the literary and iconographic tradition of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and was depicted in a wide variety of media, including woodcuts, illuminated manuscripts, frescoes, stained glass, and even sculpted stone relief.

Glued into the breviary, this woodcut invites its user to contemplate Christ’s Passion and the Eucharist. As Christ treads the grapes, his blood drips down, mixing with the juice of the fruit and draining into a chalice. With his right arm wrapped around the winepress’s upper beam, Christ pulls the press down upon himself, as if to intensify his sufferings. With God the Father above him and Mary at his left, Christ points to his pierced side—the wound most associated with the Eucharist—as though to warn the viewer not to doubt as Thomas did (John 20:24–29).

The Evangelists surround Christ, depicted by their symbols (from the Prophet Ezekiel’s vision as recounted in Ezekiel 1; cf. Revelation 4:6–8): a man (Matthew), lion (Mark), ox (Luke), and eagle (John). St Matthew, in the lower right, dips his quill into the chalice, literally writing his Gospel with Christ’s blood and thereby emphasizing the unity of Scripture with the Word made flesh (verbum incarnatum and verbum scriptum). Cascading like a waterfall of words, seven banderoles present the figures’ prayers, in which the worshipper is invited to join.

References

Gertsman, Elina. 2013. ‘Multiple Impressions: Christ in the Winepress and the Semiotics of the Printed Image’, Art History, 36.2: 310–337

Gurewich, Vladimir. 1957. ‘Observations on the Iconography of the Wound in Christ’s Side, with Special Reference to Its Position’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 20.3/4: 358–362

Parshall, Peter and Rainer Schoch. 2005. Origins of European Printmaking: Fifteenth-Century Woodcuts and Their Public (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Wilken, Robert Louis (trans.) with Angela Russell Christman and Michael J. Hollerich. 2007. Isaiah: Interpreted by Early Christian and Medieval Commentators, The Church’s Bible (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans)

Romuald Hazoumé

La Bouche du Roi, 1997–2000, Oil drums, plastic, glass, shells, tobacco, fabrics, mirrors, metal, The British Museum, London; © Romuald Hazoumé / Artist Rights Society (ARS NY); Photo: Benedict Johnson

‘Where the Grapes of Wrath are Stored’

Commentary by Angela Russell Christman

Much Christian exegesis of Isaiah 63:1–14 has focused on Christ’s Passion and the Eucharist. However, interpreters have also recognized that the passage is equally about justice, for it depicts God as both liberator of the oppressed and punisher of oppressors. St Jerome highlighted this theme in his Commentary on Isaiah, imagining that the question ‘Who is this that comes from Edom?’ (Isaiah 63:1) was posed by the angels. Not knowing beforehand about the Passion (cf. 1 Corinthians 2:6–7), they were puzzled by Christ’s bloodied appearance. According to Jerome, Christ responds:

I am the one who speaks justice … I am he who has come to fight against evil powers, to proclaim freedom to the captives and liberate from prison those in chains [cf. Isaiah 61:1]. I have come to punish my adversaries and free the captives. (Wilken 2007: 492)

In 1861 the American abolitionist Julia Ward Howe emphasized this theme of justice in Battle Hymn of the Republic, which opens by alluding to Isaiah 63:3:

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord: He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored…

Romuald Hazoumé’s La Bouche du Roi (French for ‘the Mouth of the King’) is named after the place in Benin whence enslaved Africans were shipped to the Americas in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

It consists mainly of petrol (gasoline) cans, whose anthropomorphic spouts and handles suggest the anguished faces of captives, and which are arranged to suggest the plan of a slave ship. It renews the protest against injustice voiced by Howe’s poem, but also extends it, by drawing our attention to and denouncing all forms of exploitation and their vestiges: the legacy of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century slave trade, the enslavement of people even today, the plight of refugees, economic corruption, and environmental degradation. Indeed, Hazoumé’s use of petrol cans made of plastic subtly underscores how oppression of human beings and environmental exploitation are often intertwined.

References

Snyder, Edward D. 1951. ‘The Biblical Background of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic”’, The New England Quarterly, 24.2: 231–238

Ward, Robert J. 1993. ‘Biblical Imagery in Julia Ward Howe’s “Battle Hymn of the Republic”’, The Choral Journal, 34.5: 25–27

Wilken, Robert Louis (trans.) with Angela Russell Christman and Michael J. Hollerich. 2007. Isaiah: Interpreted by Early Christian and Medieval Commentators, The Church’s Bible (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans)

Nicolas Pinaigrier

Christ in the Winepress , Early 17th century, Stained glass, Church of Saint-Etienne du Mont, Paris; CNP Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

‘Be Ready for the Pressing’

Commentary by Angela Russell Christman

In the sixteenth century, as Western Christianity began fracturing, Roman Catholic apologetics defended the doctrine of transubstantiation by elaborating on images of Christ in the winepress. A prime example, this window in St Étienne du Mont visually proclaims the unity of the consecrated wine of the Mass with Christ’s blood which it dubs ‘the nectar of life’.

Christ lies in the winepress, his blood flowing into it. Attached to the winepress’s screws, the cross crushes him. In the upper left, patriarchs of the Hebrew Bible tend ‘the vineyard of Jesus’. Below them, St Peter treads grapes in a barrel, his proximity to Christ’s head highlighting his role—and implicitly the Pope’s—as Vicar of Christ. Beneath Peter, a group carries a cask of the precious blood towards the four Doctors of the Church—Gregory the Great, Jerome, Ambrose, and Augustine—who fill barrels with grapes and Christ’s blood. On the right, two monarchs assist a pope and cardinal in storing the consecrated wine. Above Christ, the four zoomorphic Evangelists pull a chariot laden with a wine cask towards the steps of a church where confessions are heard and the Eucharist is distributed.

Today, seeking to build bridges rather than to hurl anathemas, perhaps we can mine the Church’s tradition to discover new ways of viewing and reading this luminous window. In the fourth century, Ambrose of Milan (in The Holy Spirit) likened the Church herself to the mystical winepress. Similarly, Augustine exhorted his congregation to imitate Christ, ‘the first grape’, by stepping ‘into the winepress’ and being ‘ready for the pressing’ (Boulding 2001: 85). By portraying a Church gathered around Christ and extending through time and space, St Étienne’s mystical winepress encourages all Christians to become ‘ready for the pressing’ and to share the gospel with a weary world that thirsts for ‘the nectar of life’.

References

Ambrose of Milan. On the Holy Spirit. 1963. Theological and Dogmatic Works, Fathers of the Church, vol. 44, trans. by Roy J. Deferrari (Washington: Catholic University of American Press)

Boulding, Maria (trans.). 2001. Exposition of Psalm 55, in The Works of St Augustine: Expositions of the Psalms, vol. III/17, ed. by John E. Rotelle (New York: New City Press), pp. 81–102

Mâle, Emile. 1986. Religious Art in France: The Late Middle Ages: A Study of Medieval Iconography and its Sources, trans. by Marthiel Mathews (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Thomas, Alois. 1981. Die Darstellung Christi in der Kelter (Düsseldorf: Schwann)

Caspar ? :

Christ in the Winepress (The Mystical Winepress), in Breviarium Romanum by Jakob Wolff (Basel c.1493), print pasted in front mirror, 1460–70 , Woodcut

Romuald Hazoumé :

La Bouche du Roi, 1997–2000 , Oil drums, plastic, glass, shells, tobacco, fabrics, mirrors, metal

Nicolas Pinaigrier :

Christ in the Winepress , Early 17th century , Stained glass

The Divine Charity

Comparative commentary by Angela Russell Christman

Banderoles swirl around Christ in the fifteenth-century woodcut, recording (in German) the conversation of the group gathered with him. Christ declares, ‘Love urges my heart to give the light of mercy to the world’. Thus, with the winepress bearing down upon him, Christ (re)enacts the divine charity Isaiah had described when recalling the Exodus:

I will recount the steadfast love of the Lord … according to all that the Lord has granted us, and the great goodness to the house of Israel which he has granted them according to his mercy … In all their affliction he was afflicted … in his love and in his pity he redeemed them; he lifted them up and carried them all the days of old. (Isaiah 63:7, 9)

Mary pleads, ‘God the Father, for eternity, give us your dear son in compassion’, and the Father consents, ‘Mary, here I send you my son as a reward from the throne of the Trinity’. John and Matthew beseech Christ: ‘Oh you living, sweet heart, drive the pain of sin and bitter sorrows from us poor sinners’. Mark also entreats Christ: ‘Oh, lion of the tribe of Judah [cf. Revelation 5:5], how bitter is your death. Do not let the poor sinners be lost’. Meanwhile, Luke addresses the viewer directly: ‘Oh mankind, see how very preciously Christ has sacrificed himself for our sins’.

The woodcut’s placement in a breviary invites the worshipper to participate in this dialogue. Meditating on Christ in the winepress, we might recall what Augustine wrote about the depth of divine charity: ‘You [i.e., God] are good and all-powerful, caring for each one of us as though the only one in your care, and yet for all as for each individual’ (Confessions 3.11.19).

Nonetheless, we cannot help but notice that the woodcut’s prayerful conversation speaks of mercy for the world. Even Luke addresses not just the individual gazing at the woodcut, but humankind. While Augustine’s remark implies that Christ would have trodden the winepress for only one person in need of salvation, it also links the individual to the community through the embrace of divine charity. Thus, the offer of salvation always includes the call to join the people of God, a body that transcends time and space.

The Mystical Winepress of St Étienne du Mont displays this gathered community, one not limited by confines of time and space. The people of God throughout the ages are arrayed around Christ’s suffering body: patriarchs tending the Lord’s vineyard, the apostle Peter crushing grapes, the four doctors of the Church, worshippers of Nicolas Pinaigrier’s own time, and even those who view the window today and find themselves in it.

‘Who is this that comes from Edom?’ The divine response, ‘It is I, announcing vindication, mighty to save’ (Isaiah 63:1), reminds us—as it did St Jerome in his Commentary on Isaiah—that God’s redeeming action always involves vindication of those who have been oppressed (and punishment of their oppressors). In a cosmic sense, redemption and vindication bring freedom from slavery to sin and death (cf. Revelation 19:11–16). However, this cosmic sense can never be severed from concrete historical reality: the gift of salvation brings with it commands to feed the hungry, to deal justly with neighbours, and to welcome sojourners in our midst (cf. Leviticus 19) or, in Jesus’s words, to care for ‘the least of these’ (Matthew 25:40).

Romuald Hazoumé’s arresting installation forces us to acknowledge the past and present violations of these divine commands.

Deliberately arranged so as to echo a print of the Liverpool slave ship Brooks, which was produced in the eighteenth century to protest against the inhumanity of the slave trade, La Bouche du Roi confronts us with the horrors of slavery that exist even today. Its boat-like shape evokes the plight of refugees. The 304 plastic petrol cans remind us of the sins of greed, corruption, environmental exploitation, and enslavement of our fellow human beings, which have too often been justified by perverse interpretations of the Bible. The voices of the oppressed—suggested by the open spouts of petrol cans—cry out for the liberation and redemption Isaiah prophesied (63:4). Those who doubt that the divine charity will vindicate the oppressed invite the vengeance described by the prophet. We are reminded that the words of Scripture are not moribund, but speak as eloquently today as they have in the past.

References

Augustine. Confessions. 1991. Trans. by Henry Chadwick (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Parshall, Peter and Rainer Schoch. 2005. Origins of European Printmaking: Fifteenth-Century Woodcuts and Their Public (New Haven: National Gallery of Art in association with Yale University Press)

Wilken, Robert Louis (trans.) with Angela Russell Christman and Michael J. Hollerich. 2007. Isaiah: Interpreted by Early Christian and Medieval Commentators, The Church’s Bible (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans)

Commentaries by Angela Russell Christman