Jeremiah 1

An Infinite Calling

Unknown artist

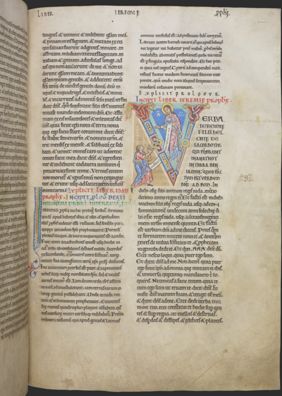

Illuminated initial V depicting the Vocation of Jeremiah, from Dover Bible, vol. I (Bibliorum Pars I), 12th century, Manuscript illumination, Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge; MS 003, fol. 195r, Courtesy of The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Rich Words, Poor Words

Commentary by Gabriel Torretta, O.P.

The story of the vocation of Jeremiah conveys a series of dramatic paradoxes: that the words of the book are both Jeremiah’s and God’s (Jeremiah 1:1–2); that Jeremiah has no authority to speak and yet speaks with God’s own authority (vv.6, 9); and that by prophesying specifically to Judah, Jeremiah prophesies to all the nations (vv.5, 17).

The anonymous illuminator of the Dover Bible (twelfth century) finds unity in these disparate ideas, using a miniature in the first letter of the first chapter to interpret the whole book in the light of Jesus Christ. Jeremiah and Christ face each other across a divide created by the left arm of the letter V in verba (‘words’). Jeremiah stands to the left of the initial with his mouth open, and from his lips come the first words he speaks in Jerome’s Vulgate translation: ‘Ah, ah, ah, Lord God’ (v.6). Christ, standing within the ‘V’, has his mouth closed but from his hand a scroll unfurls across the divide and touches Jeremiah, inscribed with the words: ‘I have made you a prophet to the nations’ (v.5).

In this illuminated initial, as in the story itself, God’s abundance is contrasted with human poverty. The interior space of the V where Christ stands is richly filled, painted in two tones of celestial blue; by contrast, Jeremiah stands on an earthy beige field. Christ is identified with the Greek letters Alpha and Omega inscribed on either side of him (cf. Revelation 1:8), while Jeremiah’s open mouth pours out ‘baby’ sounds: a, a, a. But the seemingly insurmountable divide between the figures is in fact bridged by a gift from God: the words of the prophecy.

The image portrays the vocation of Jeremiah as infinitely more than a mere imparting of information from God to Jeremiah: in receiving the words of God, Jeremiah receives the Word of God, and hands the Word on to his people. The abundant life of God rushes out through words that are both Jeremiah’s and God’s, calling first Judah and then the whole world to leave the contradictions of human weakness behind and to be drawn into the paradoxes of God’s infinite mercy.

William Congdon

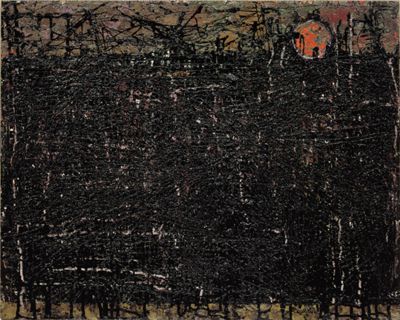

Black City on Gold River, 1949, Ink, oil, and enamel on masonite, 96 x 78 cm, William G. Congdon Foundation, Buccinasco, Italy; © William G. Congdon; Photo Courtesy The William G. Congdon Foundation

Dark’s Light

Commentary by Gabriel Torretta, O.P.

The first moments flowing from the vocation of Jeremiah are dark and cold: ‘Out of the north evil shall break forth upon all the inhabitants of the land’ (Jeremiah 1:14), and ‘every one shall set his throne at the entrance of the gates of Jerusalem, against all its walls round about, and against all the cities of Judah’ (v.15), and ‘I will utter my judgments against them’ (v.16). A long night has settled upon the land, and God plunges Jeremiah into its midst. He offers him no great weapons, no masterful rhetoric, no earthly patron.

New York City, 1948. William Congdon, a young artist who has fought in World War II and seen concentration camps firsthand—leading him to a bitter rejection of his Puritan upbringing—experiences an artistic conversion. Drawn into the orbit of Jackson Pollock, he leaves behind the Classical Realism of his artistic training and embraces Abstract Expressionism, turning the cityscape around him into impastoed canvases heaped with paint, violently and endlessly scored with an awl.

A year later, a pattern seems somehow to have crept into his mind, working itself out in an unintentional series of paintings. The city begins to appear as a monstrous dying form, bleeding from a thousand wounds. In this 1949 work, the black mass of the city seethes and writhes, struggling even in its death throes to swallow the river, to blot out the sky. Its bulk overwhelms the canvas, seeming to press the sky against the upper edges of the composition. Yet somehow, cruelly burdened and partially obscured, one light still shines: a disc of gold.

Jeremiah’s prophetic vocation is born in darkness, the gloom of the people’s ‘wickedness in forsaking me’, their burning ‘incense to other gods’, their worshipping ‘the works of their own hands’ (v.16). The people of God will be driven out, overwhelmed, and pressed out of their land. The holy city will die from within, its glorious life swallowed up and blotted out by the consuming death of idolatry and sin. But this prophet, who will be mocked, ignored, and beaten, is given to the people of Judah to be an unquenchable disc of gold: ‘for I am with you, says the LORD, to deliver you’ (v.19).

References

Congdon, William. 1962. In My Disc of Gold: Itinerary to Christ (New York: Reynal & Company)

Andrew Wyeth

Snow Hill, 1989, Tempera on panel, 83.82 x 116.84 cm, Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection; © Andrew Wyeth / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo: Peter Philbin

A Remembered Present

Commentary by Gabriel Torretta, O.P.

‘Before I formed you in the womb I knew you’, says the Lord to Jeremiah, ‘and before you were born I consecrated you’ (Jeremiah 1:5). The Lord reveals that he has always been at the heart of things, always suffusing the scattered moments of Jeremiah’s life with a generative knowledge and a transformative love. But Jeremiah can’t yet see the Lord face to face; he sees him only through the prism of memory.

Six figures holding brightly coloured ribbons dance around a maypole incongruously jutting out of a snowy hilltop, overlooking train tracks, a fence, and some scattered rural buildings. A seventh ribbon floats untended. Atop the pole stands an evergreen tree, somehow both apart from and a part of what happens below.

Snow Hill, one of Andrew Wyeth’s most unexpected and gripping works, comes to life as memory: each of the six figures represents a person who had been important to Wyeth, many long dead, each represented as they appeared in earlier paintings by the artist. Similarly, the structures in the landscape at the foot of the hill recreate spaces from Wyeth’s past—once-significant and now lost.

The seventh, open spot around the maypole seems to invite the viewer to find a suitable addition to the dance: Wyeth himself? His wife? Another ordinary figure from Wyeth’s seventy-year-long life captured in the amber of his previous paintings? Someone new, as yet unknown? The viewer, perhaps?

The unexpected evergreen perched implausibly on the maypole prevents the work from being a mere performance of retrospection or nostalgia. There is something perpetually present-tense about its presence, as if it has always been there, and has always been green. Almost imperceptibly, it unites the manifold pasts of the painting into a single time-defying now.

Speaking both to the great and to the humble, Jeremiah sees visions of desolation. He is disbelieved, imprisoned, abandoned. He is alone. God seems to hide. The circle of memory stays broken, and an untended ribbon escapes his grasp. But Jeremiah’s life is not a mere conglomeration of raw facts; it is a perpetual dance that takes its shape from the Unchanging One whose presence makes it real. He knows ruin is coming—and redemption.

References

Junker, Patricia. 2017. ‘Reflection, 1989–2009’, in Andrew Wyeth: In Retrospect, ed. by Patricia Junker and Audrey Lewis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017): 182–87

Meryman, Richard.1996. Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life (New York: HarperCollins), 415–16

Unknown artist :

Illuminated initial V depicting the Vocation of Jeremiah, from Dover Bible, vol. I (Bibliorum Pars I), 12th century , Manuscript illumination

William Congdon :

Black City on Gold River, 1949 , Ink, oil, and enamel on masonite

Andrew Wyeth :

Snow Hill, 1989 , Tempera on panel

Discomfiting Intimacy

Comparative commentary by Gabriel Torretta, O.P.

God calls Jeremiah to a desolate and solitary vocation: to be the last prophet at the end of an age, to be rejected and despised for calling the people back to God. Jeremiah 1 recounts the sinfulness of the people, the wrath of God, the impending trials of Jeremiah’s life, and the devastating collapse of Jerusalem. Yet this tapestry of doom is shot through with threads of brilliant gold: ‘Before I formed you in the womb I knew you’ (v.5); ‘I am with you to deliver you’ (v.8); ‘I have put my words in your mouth’ (v.9).

The Dover Bible miniaturist expresses the contrasting threads of distance and intimacy, trial and comfort, by representing the distance between God and Jeremiah through symbolic space and attributes of omnipotence and impotence respectively. Yet however much the word of God seems to be a barrier between the two figures, the prophetic vocation of Jeremiah spills out of Christ’s heart, impossibly transcending the limits of space and time, and comes to rest on Jeremiah. Jeremiah is solitary and set apart, but in being filled with the words of God, he is filled with God’s own heart, and is called to draw others to share in that union.

Andrew Wyeth’s Snow Hill uses retrospective vision to explore the strangeness of time and memory. He recognizes that the seemingly random series of joys, tragedies, encounters, and separations that makes us who we are nonetheless depends in a curious way on an unchanging something. In the viewer’s mind and memory, perhaps that something can be revealed as Someone in whom all our confused chronologies are united in a timeless moment. And from such a Someone, new and wholly unlooked-for meanings may emerge. Seen through the lens of Jeremiah 1, the mysterious evergreen can take on new significance as a visual token of God’s intimate knowledge of the individual. The Snow Hill vision both comforts and unsettles: there is peace in knowing that the moments of our lives have their meaning as held in God, but a disturbing honesty in realizing that the presence of this Someone and the meaning he makes may only be revealed to us in memory.

William Congdon’s Black City on Gold River can help to bring out the ominous character of Jeremiah’s vocation: the dark mass of idolatry and wickedness with which Jeremiah is confronted has metastasized and spread until it has consumed the land, leaving no natural hope for the return of the light. This is the world Jeremiah is called to speak the words of God to; this world, which can no longer be his home, must be his dwelling for as long as he carries out his prophetic message. And yet all is not lost. Just as the strange disc of gold in Congdon’s work seems in danger of being swallowed up by ravening tongues of darkness but is not extinguished, so—before, during, and after ‘the captivity of Jerusalem’ (v.3)—God’s promised presence abides: ‘for I am with you, says the LORD, to deliver you’ (v.19).

The Lord promises Jeremiah not peace, but intimacy with himself—still more, God reveals that he has known and loved Jeremiah from before his birth, and that the specific prophetic calling Jeremiah receives is a confirmation and shaping of the intimacy he has always had with God. This new stage of intimate union with God—where Jeremiah’s words are God’s words and God’s words are Jeremiah’s words—necessarily unfits Jeremiah for life in a society where the service of God is not prized. Taken up with the knowledge and love of God, Jeremiah cannot help but be ‘a fortified city, an iron pillar, and bronze walls, against the whole land’ (v.18). This is because the very shape of his vocation is to receive good gifts from God in a way that broadcasts them to others; that likewise invites the people to be unsettled from their idolatries and disobedience and to be drawn themselves into radiant intimacy with God.

This is an intimacy that discomfits, that cannot be content with half-measures and partial devotion. It must ‘pluck up’ and ‘break down’, ‘destroy’ and ‘overthrow’, ‘build’ and ‘plant’ (v.10), because everything that does not come from God and lead back to him in worship must be torn out, so that the intimate union God planned from the beginning can bear good fruit.

Commentaries by Gabriel Torretta, O.P.