Isaiah 13:1–14:27

Destruction in Progress

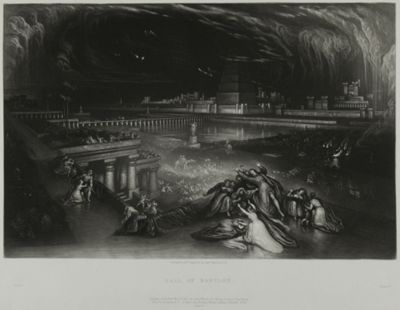

John Martin

The Fall of Babylon, from Illustrations of the Bible, 1835, Mezzotint with etching in black on ivory wove paper, Sheet: 329 x 416 mm, The Art Institute of Chicago; John H. Wrenn Memorial Endowment, 1991.216.17, Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Destruction Begins

Commentary by Alyssa Elliott

Rendering a scene of the city falling to invading forces, this mezzotint shows the beginning of the end for Babylon. When viewed alongside this passage from Isaiah, it becomes a vivid depiction of the violence of the prophecy. It puts faces on the people of the city and captures the image of what will be lost as the destruction begins.

The people in the rooftop garden in the foreground have fallen to their knees at the sight of the destruction. ‘Pangs and agony will seize them; they will be in anguish like a woman in travail’ (Isaiah 13:8). Their hands are outstretched as though petitioning the heavens for the violence to cease. To the left, on a different part of the roof, a crowd runs from the battle below. Isaiah’s prophecy makes clear, however, that flight is futile. The invaders ‘have no regard for silver and do not delight in gold. Their bows will slaughter the young men; they will have no mercy on the fruit of the womb; their eyes will not pity children’ (vv.17–18). Defending soldiers fight back, but the chariots of the invading army are racing into the city.

At the right of the composition, fires burn in what could be fields or homes, leaving the city uninhabitable and desolate (vv.20–22) and columns of smoke draw the viewer’s gaze upward. The black sky over the scene echoes how Isaiah describes the day of the Lord: ‘For the stars of the heavens and their constellations will not give their light; the sun will be dark at its rising, and the moon will not shed its light’ (v.10).

Babylon is poised for destruction. Isaiah’s prophecy is made manifest in ink turned to fire and smoke as a standing city prepares to fall.

Unknown Italian artist

The Fall of the Rebel Angels, by an unknown Italian artist, Early 18th century, Ivory, 27.31 x 15.24 cm, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO; William Nelson Trust through the George H. and Elizabeth O. Davis Fund, 69-2, Image courtesy Nelson-Atkins Media Services

After the Day Star

Commentary by Alyssa Elliott

One early Christian interpretation of Isaiah 14:12–22 was to read it as an account of Satan’s fall from being the Day Star to a Dragon (Origen, On First Principles: 1.5.4–5; Eusebius, Proof of the Gospel: 4.9; Augustine, Teaching Christianity 3.37). This interpretation has continued to be influential on Christian readings of this passage and is the basis of this eighteenth-century Italian sculpture.

The Day Star of Isaiah 14 said, ‘I will ascend above the heights of the clouds, I will make myself like the Most High’. (v.14). There is no Day Star above the clouds in this highly detailed ivory carving, only God depicted in the form of the three persons of the Trinity. Robed angels look up towards God from the top of the sculpture as demons fall to hell below. These demons were once angels themselves but are now transformed from figures robed in glory into naked, grotesque beings, whom angelic warriors pursue with spears and swords. The fallen Day Star of Isaiah, perhaps represented by the open-mouthed dragon devouring demons at the base of the sculpture, has not fallen alone as these rebel angels join him in the depths.

This sculpture evokes that destruction as it happens, depicting an instant half-way through this fall. The angels at the top of the scene show what the Day Star and these demons once were, and what they have lost. It takes the taunting of Isaiah, ‘Is this the man who made the earth tremble, who shook kingdoms, who made the world like a desert and overthrew its cities, who would not let his prisoners go home?’ (Isaiah 14:16–17) and throws it at Satan. The one once called the son of Dawn, who sought to become like God, has become a beast confined to a pit, devouring his people and destroying all who followed after him.

References

Behr, John (trans.). 2019. Origen of Alexandria, On First Principles (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Ferrar, W.J. (trans.). 1920. Eusebius of Caesarea, Proof of the Gospel, vol. 1 (New York: The Macmillan Company)

Hill, Edmund (trans.). 1996. Augustine of Hippo, Teaching Christianity (New York: New City Press)

Vivan Sundaram

Death of Akkadian King, 1991, Engine oil and charcoal on paper, 762 x 1117.6 mm (on two sheets of paper), Private collection; Photo courtesy of the Estate of Vivan Sundaram

Gulf War in Babylon

Commentary by Alyssa Elliott

As the Gulf War in the 1990s raged in Iraq, Vivan Sundaram created his series of drawings: Engine Oil and Charcoal on Paper. Each drawing in the series was made with homemade paper, charcoal, and used and discarded engine oil. Saloni Mathur reflects on this body of work saying, ‘[Sundaram] returns us to the land as a kind of bedrock in which oil, antiquities, and the past reside—and upon which economies, nations, and wars are built—and it reminds us of the devastating impact of war on the physical and historical environment of a region’ (Mathur 2019: 71).

Here, the head of an Akkadian king falls towards the bottom edge of the page, calling to mind Isaiah’s taunt to the king of Babylon: ‘Your pomp is brought down to Sheol, and the sound of your harps; maggots are the bed beneath you, and worms are your covering’ (Isaiah 14:11). Viewed from a distance, the clouds of charcoal and used engine oil evoke the maw of a beast ready to devour. This oil, extracted from below the earth before being spilled upon the land, acts as a ‘welcoming committee’ for the king. As the king of Babylon is struck down, Isaiah says, ‘Sheol beneath is stirred up to meet you when you come’ (v.9).

The black cloud in the centre of the composition can represent more than rising Sheol. These clouds of oil break out from under the earth and rip open the land. Registering the contemporary violence of the Gulf War, the human figures on the right and the remnants of Babylon on the left are blown away and destroyed.

Sundaram’s image invites the viewer to reflect on what is lost in such great destructions. Considered alongside the passage from Isaiah, we are forced to think beyond what will happen after Babylon is destroyed. The totality of the destruction is made clear in the passage, but this image suggests that more is lost in war than just people. Ancient history is toppled and its people are buried beneath black clouds. The land becomes a place for wild animals in Isaiah, but not even they can survive in a land bleeding oil.

References

Mathur, Saloni. 2019. A Fragile Inheritance: Radical Stakes in Contemporary Indian Art (Durham, NC: Duke University Press)

John Martin :

The Fall of Babylon, from Illustrations of the Bible, 1835 , Mezzotint with etching in black on ivory wove paper

Unknown Italian artist :

The Fall of the Rebel Angels, by an unknown Italian artist, Early 18th century , Ivory

Vivan Sundaram :

Death of Akkadian King, 1991 , Engine oil and charcoal on paper

Viewpoints of Destruction

Comparative commentary by Alyssa Elliott

Babylon’s destruction begins and ends in these prophecies from Isaiah. They are the beginning of a long section of prophecies against the nations around Israel. A distinct section like this is common in the longer prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible (Blenkinsopp 1996: 175). Most likely written in the sixth century BCE as Babylon loomed large over Israel, this passage is a cry of the oppressed against their oppressors (Brueggemann 2003: 196).

This passage describes a violent end to both the Babylonians and another hostile and powerful neighbour, the Assyrians. The prophet not only details the destruction that will come upon the land, but it also narrates the fall of the king of Babylon in a cosmic perspective—a fall from heaven to a welcome in Sheol. The three artworks discussed here highlight the violence described in the passage and give insight into its different layers of meaning and interpretation. They look upon the moment of destruction from different viewpoints, each providing a different way to interpret Isaiah’s words.

John Martin’s mezzotint The Fall of Babylon imagines a historical moment in which the city itself is destroyed, succumbing to divine wrath and human violence. The foreground highlights the personal anguish felt by the people in the city. In the background, bolts of lightning hint at a divine source for this destruction. Obscured under a layer of smoke, a battle rages and the inhabitants of the city are killed.

A carved ivory sculpture by an unknown eighteenth-century artist, The Fall of the Rebel Angels, interprets this passage as a description of cosmic events. It follows an established Christian tradition of interpreting Isaiah 14 as a description of Satan’s fall from heaven. As the figures fall in the sculpture, their features change into that of demons. They are pursued and attacked by heavenly warriors until they finally fall to the bottom and are consumed by a beast.

Finally, Vivan Sundaram’s Death of Akkadian King speaks to what is lost in a destruction like this. Sundaram created the series Engine Oil and Charcoal on Paper, to which this work belongs, after a visit to Iraq in the late 1980s. He challenges the viewer to consider the collective loss of war in the destruction of land, culture, and history.

There is an energy to each artwork, but the chaotic fervour conveyed by Sundaram is a distinct contrast to the organized and balanced movement in the mezzotint and the ivory. Martin draws the viewer’s eyes from foreground to background, from individual grief to heaven-sent lightning and smoke. The sculpture is topped with an image of the Trinity and the eye is drawn downward, tracing the fall of the angels, before ending, at the foot of the sculpture, with Adam and Eve’s exile from Eden. Sundaram’s drawing sends the viewer’s eye back and forth across the paper, drawing us in to see the details of the fallen head of a king at the left and then back out to view a scene nearly obscured by clouds of engine oil and charcoal.

The ways the artists guide their viewers’ eyes open different perspectives from which to read the scriptural text.

For Martin, the passage becomes a graphic narration of a moment in history. The viewer is an eyewitness to that which Isaiah predicted as the city is consumed by smoke and death.

The ivory sculpture looks into the supernatural realm, drawing the eyes of the viewer down from heaven to Sheol.

Sundaram brings the dead Babylonian king and destroyed land to the twentieth century. When viewed alongside this passage, the reader must consider what happens when such violence does not end.

All these artworks place an emphasis on destruction in different ways. The grandeur of the Babylonian ziggurats reaching for the heavens is obscured by smoke and fire, angels become demons to be consumed by a beast, and kings are toppled and covered in black clouds of oil.

But each is a destruction still in progress. What is being lost to the violence is not yet entirely vanished. And as long as something remains, so too does hope. In the ivory sculpture Adam and Eve are banished from the garden as angels become demons. Yet, atop it all, Christ holds a cross—a sign that even from this destruction there might be something to be made new.

References

Blenkinsopp, Joseph. 1996. A History of Prophecy in Israel (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press)

Brueggemann, Walter and Tod Linafelt. 2003. An Introduction to the Old Testament: The Canon and Christian Imagination (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press)

Roberts, J.J.M. 2015. First Isaiah: A Commentary (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press)

Commentaries by Alyssa Elliott