Job 28

Where Shall Wisdom Be Found?

John Constable

Study of Cirrus Clouds, c.1822, Oil on paper, 114 mm x 178 mm (estimate), Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Given by Isabel Constable, 784-1888, V&A Images, London / Art Resource, NY

An Off-Stage Sun

Commentary by Spike Bucklow

In the nineteenth century, English artist John Constable took up the tradition of landscape painting. This genre had developed, along with seascapes, in seventeenth-century Holland. Constable is known for his particular attention to the habits and moods of the sky, and this sketch rehearses cloud forms that would find a place in later paintings.

It was painted a decade or so after William Wordsworth began his most famous poem with the line ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’ (written between 1804 and 1807; revised 1815). However, Constable’s approach to clouds was rather less Romantic than the poet’s, and was mixed with the scientific. Constable owned, and annotated, a copy of Thomas Forster’s influential Researches about Atmospheric Phaenomena (1813), which included a series of engravings of clouds. Forster briefly outlined the history of meteorology and acknowledged that, whilst it may have been of use to ancient shepherds, it would be wrong to suppose the science’s origins lay in its utility alone (1813: vi–vii). The science of meteorology included pleasure in observing the heavens.

Clouds sometimes appear in the Bible as harbingers of doom; they cast darkness upon the land (e.g. Ezekiel 30:18; 32:7; Joel 2:2; Zephaniah 1:15). In Job, they form ‘a decree for the rain, and a way for the lightning of the thunder’ (28:26) as well as the ‘whirlwind’ source of God’s voice (38:1). Yet Constable’s gentle clouds are lit by an off-stage sun and seem like ‘swaddling-bands’ (38:9), which imply protection for creation as a new-born babe. Constable’s loving attention to detail suggests that the artist’s eye ‘sees every precious thing’ (28:10), like those in search of wisdom.

However, Job reminds us that study of the heavens holds no guarantees in the search for wisdom. After all, ‘[t]hat path no bird of prey knows, and the falcon’s eye has not seen it’ (28:7). ‘It is hid from the eyes of all living, and concealed from the birds of the air’ (28:21)—creatures whose knowledge of clouds was surely superior to Wordsworth’s, Forster’s, or Constable’s.

References

Forster, Thomas. 1823. Researches about Atmospheric Phaenomena, 3rd edn (London: Harding, Mavor, and Lepard)

James McNeill Whistler

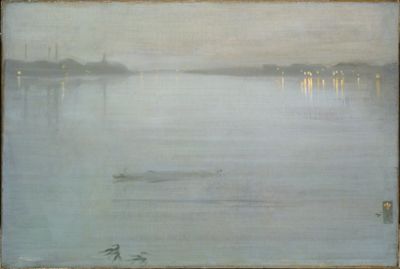

Nocturne: Blue and Silver–Cremorne Lights, 1872, Oil on canvas, 50.2 x 74.3 cm, Tate; N03420, © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Long Rumours of Wisdom

Commentary by Spike Bucklow

This painting is a view from London’s Battersea Bridge, looking upstream. The lights of Cremorne Pleasure Gardens and their reflections in the Thames are on the right, and the lights and chimneys of Battersea are on the left. The broad river, night sky, and blurred skyline are all painted wet-in-wet in blended shades of grey whilst, by way of contrast, the small lights and reflections are crisply defined spots and streaks of yellow, added once the greys were dry.

This quiet work was one of a series that caused a storm when first displayed. In an open letter, the critic John Ruskin accused James McNeill Whistler of ‘flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face’ (Fors Clavigera no.79). A court case ensued and, in 1878, Ruskin argued that the Nocturnes glorified urban industrialization and lacked moral or didactic purpose—things he believed to be primary functions of visual art. He thought the paintings superficial and sensationalist. Whistler won the case but was awarded token damages, was bankrupted, and had to leave the country.

As the book of Job recounts, the misfortunes that can beset us come in many forms and can be very unexpected. Ruskin, for example, thought he was defending the moral high-ground but the court case precipitated the end of his career. The visual arts may depict afflictions, but they can also be the result of them (like Goya’s late work Yard with Lunatics, c.1793–4, painted after an illness; Connell 2004) or even, as in this case, their cause.

Whistler managed to rebuild his career in Venice and Paris, and received several international awards through the 1880s and 90s. The Nocturnes are no longer taken as an affront to the unsuspecting public; their delicate qualities are now widely appreciated and Whistler’s work is recognized as influencing subsequent generations of painters. However, arguments similar to Ruskin’s have been levelled against many artists in the intervening 140 years.

The ‘rumour’ of wisdom (v.22), like that of artistic merit, can take a long time to corroborate.

References

Connell, Evan S. 2004. Francisco Goya: A Life (New York: Counterpoint)

Ruskin, John. 1891. ‘Letter 79’ in Fors Clavigera: Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain, vol. 4 (Philadelphia: Reuwee, Wattley & Walsh), pp. 61–75 [73]

Sutherland, Daniel E. 2014. Whistler: A Life for Art’s Sake (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Ludolf Backhuysen I

Ships in Distress off a Rocky Coast, 1667, Oil on canvas, 114.3 x 167.3 cm, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1985.29.1, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Precarity

Commentary by Spike Bucklow

The seventeenth century saw a new genre of Dutch paintings quickly establish itself. These paintings were made not for church or court, but for ordinary citizens, and this seascape is one example. It shows three Dutch cargo ships in a stormy sea off some inhospitable foreign coast, their distance from home being evident from the shoreline which is quite unlike that of the Low Countries. Many seventeenth-century Dutch mariners lost their lives in the circumstances the painting depicts.

The majority of seventeenth-century Dutch merchants built their fortunes by trading with the East, buying spices and porcelain. Mariners risked their lives at sea, and their employers’ livelihoods were also at risk from the passage to and from China. For them, shipwrecks spelt disaster and fortunes were lost as ships foundered. If this painting originally hung in a Dutch merchant’s house, it would have been a reminder that his worldly wealth was vulnerable.

Seascapes were often displayed over doorways as reminders of the perils associated with passage from one state to another. The painting could have physically hung at a threshold between rooms, but its position may have symbolized the dangers of all transitions—those associated with economic exchanges, and also those of exchanges with the divine.

The book of Job suggests that the nature of both such exchanges is inherently ‘precarious’ (a word etymologically related to ‘prayer’). The ‘ends of the earth’ are known only to God (Job 28:24). In Job, the pursuit of worldly wealth ‘to the farthest bounds’ (28:3) is compared to the search for wisdom, and in both cases the pursuer’s whole existence is at stake. Appropriately, the mariners in this painting, like the miners in Job 28, ‘swing to and fro’ above ‘the deep’ (vv.4, 14).

Merchants invested money in the hope of greater returns. But of course, as the painting shows, things can go awry. If the ship also represents the turbulent voyage of the soul on its way through life, then it is a worthy support for meditation on the whole book of Job, which is about how a rich man’s faith was tested by the loss of his wealth.

John Constable :

Study of Cirrus Clouds, c.1822 , Oil on paper

James McNeill Whistler :

Nocturne: Blue and Silver–Cremorne Lights, 1872 , Oil on canvas

Ludolf Backhuysen I :

Ships in Distress off a Rocky Coast, 1667 , Oil on canvas

Immersive Experience

Comparative commentary by Spike Bucklow

Biblical Wisdom literature has parallels across the ancient Near East, including Egyptian texts that dwell upon issues of human suffering within an encyclopaedic view of nature. Examples include: ‘A Dispute over Suicide’, ‘The Protests of the Eloquent Peasant’, and ‘The Instruction of Amen-em-Opet’ (Pritchard 1969: 405–10, 421–4; Hartley 1988: 6–11). Like them, the book of Job acknowledges that worldly experiences can lead to spiritual insights.

Amidst a story of suffering, Job 28 starts with an overview of worldly knowledge and skill, celebrating the extraordinary powers of humans, who can even ‘overturn mountains by the roots’ (v.9). It conditionally validates what we might think of today as scientific enquiry into the world; ‘the thing that is hid he brings forth to light’ (v.11). Yet such enquiries are not sufficient: ‘where is the place of understanding? Man does not know the way to it’, because wisdom is not found ‘in the land of the living’ (vv.12–14). Verse 28 suggests that one has to be personally transformed, by ‘fear of the Lord’, in order to see beyond the mere stuff of the world. Such transformative experiences destroy the ‘objectifying’ detached observer, opening possibilities for participative knowledge.

The creation and appreciation of paintings necessarily involve participative knowledge. I have chosen three paintings for their capacity to elaborate Job 28:25—‘he gave to the wind its weight, and meted out the waters by measure’. Two of the paintings focus on the ‘measure’ of water. Ludolf Backhuysen’s painting is representational and full of contrast, whilst James McNeill Whistler’s verges on the abstract and is subtly modulated. These technically different ways of making paintings influence the way we read them, as challenging or relaxing.

Backhuysen depicts water naturally lit by the sky by day, whilst Whistler depicts water artificially lit by humans at night. In the Backhuysen, the tempestuous water is wild and envelops the sailors, whereas in the Whistler, the tranquil water seems tamed and is enveloped by city-dwellers. The contrasts between them reflect the contrasting states—wealth and poverty, sickness and health, etc.—in the story of Job’s afflictions. They also reflect the contrasts in Job 28, between that of which man is capable (vv.1–22) and that of which God is capable (vv.23–27). After all, Whistler’s Garden is London’s Cremorne, not Eden. The Whistler painting celebrates mankind’s apparent ability to channel water, whilst the Backhuysen reminds us of the limits of human power.

Backhuysen and Whistler both establish their moods with water; it is crashing waves that threatened the intrepid mariners and twinkling reflections that entrance the urban stroller. But, critically, in both, what lies below the horizon reflects what is above the horizon—what is happening in the world depends upon the heavens. In the paintings we see violent waves or gentle ripples, but the waters are animated by wind (Greek anemos) which is not seen.

John Constable’s picture, looking towards the heavens, therefore reminds us that ‘He gave to the wind its weight’ (Job 28:25). It also summons the primordial image of the spirit ‘moving over the face of the waters’ (Genesis 1:2). Constable’s study has no dividing horizon line. It is a meditation upon the ceaseless actions above, which, invisibly, impact upon everyone below.

Of course, we can choose how to respond to what happens in the world. So, reflecting the relative powers of man and God contrasted in Job 28, our response to the world can also contrast—we can strive for silver and gold (v.1) or for wisdom that is beyond the price of silver and gold (v.15). Our motives can be superficial or profound, just as our means can be objectifying or participatory.

Waves can be objectively understood through mathematical modelling—this is how nautical engineers calculate the resilience of ships’ hulls and how software engineers make special effects for apocalyptic movies. Alternatively, waves can be known in the manner of the sailor or surfer—as one who joins in with creation: terrifying, exhilarating, or calming, but in every case awe-inspiring. The first approach involves filtering out those parts of the phenomenon that cannot be entered as computer data. The second approach involves complete immersion, whether by accident, as a thrill seeker, or vicariously by the exercise of empathy and imagination. The first treats the Book of Nature as a code to be cracked whilst the second enters into it as the Creator’s autobiography, feeling His wrath in one picture, His mercy in another, and the mystery of His ways in a third. In sailing or surfing terms, wisdom may involve having the courage to ride the wind and waves, wherever they may take us.

References

Hartley, John E. 1988. The Book of Job, New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans), pp. 6–11

Kelsey, David H. 2009. Eccentric Existence: A Theological Anthropology (Westminster John Knox Press), p. 193

Pritchard, James B. (ed.). 1969. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3 edn (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press)

Commentaries by Spike Bucklow