Job 1–3

A Man in the Land of Uz

Wilhelm Heinrich Otto Dix

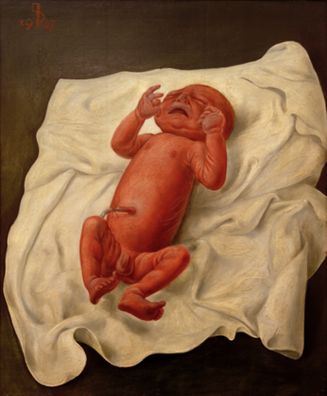

Baby with Umbilical Cord, 1934, Oil on canvas, Permanent loan to Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden; © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn; Photo: akg-images

Naked I Came from my Mother’s Womb

Commentary by Ursula Weekes

Wilhelm Heinrich Otto Dix’s Baby with Umbilical Cord (1927) is the kind of painting that you just cannot walk past. It depicts the artist’s son Ursus moments after birth when his mouth, hands, and feet are still purple and he cries to oxygenate his body.

Healthy though these signs are, they nonetheless create an unsettling image. The umbilical cord is freshly cut: this new life must survive alone in the world. The baby’s solitary struggle anticipates human suffering and loneliness.

When Job loses his wealth and his children in one disastrous day, he gives us the first taste of the poetry that will dominate thirty-nine chapters of the book: ‘Naked I came from my mother’s womb and naked I shall return…’ (Job 1:21).

Satan is responsible for the evil. He is the simius dei, the ‘ape of God’ to use an idea derived from Tertullian (De Baptismo 5.3), masquerading as God, making God seem unfamiliar to Job. But it is with the one true God that Job wants to do business. He knows that God is sovereign over this adversity, calling him three times by his covenant name ‘YHWH’: ‘The LORD gave and the LORD has taken away. Blessed be the name of the LORD’ (v.21).

As his identity is stripped back by loss, Job rends his robe, shaves his head, and falls in worship before God. It is a moving act of faith shaped by the ritual norms of his society. But after Satan has covered Job in painful sores (2:7), and his three friends arrive (2:12–13), a more elemental quest for truth drives the existential poetry of Job’s complaint in chapter 3. Job refuses to curse God, which Satan and his wife both suggest, but as the book moves from prose to poetry, he curses the day of his birth (3:1).

‘Why did I not die at birth, come out from the womb and expire?’ (3:11). This is an agonizing lament in which Job desires creation to be un-made and wishes that his very existence had been obliterated before he took his first breath. While Otto Dix’s painting conjures the perilous proximity of life and death as it emerges from the womb, Job’s words, for his own part, call for death to have the upper hand.

Unknown artist

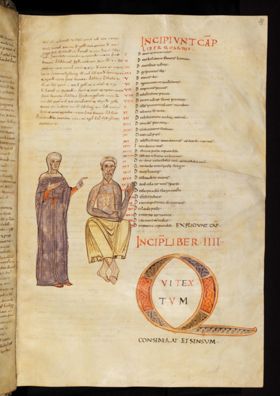

Illustration from Moralia in Iob (Job) by Saint Gregory the Great, 1061, Illumination on parchment, 51 x 34 cm, Bamberg Staatsbibliothek; MS Bibl. 41, fol. 29r, Staatsbibliothek Bamberg, Photo: Gerald Raab

Job and his Wife

Commentary by Ursula Weekes

In Job 2:9, Job’s wife makes a cameo appearance and asks her husband, ‘Are you still holding fast to your integrity? Curse God and die’. The Hebrew word she uses (barak) typically means ‘bless,’ but there is little sign of blessing here, and either way Job is being asked to die.

His wife has given up hope because she has lost everything too. The only thing remaining is the ignominy of her husband’s putrid suffering and therefore she is bitter of soul.

Job’s wife feels real. She doesn’t say the ‘right things’. She’s just honest about losing her faith. God has apparently confounded the terms of his covenant to bless the upright, and therefore he appears arbitrary. Job, meanwhile, is resolute in the face of his wife’s words, but is he also more tender than we might think? In 2:10 he does not say she is foolish, just that she speaks like a foolish woman. From then on, Job’s wife will be silent during her husband’s long quest to understand God’s justice, but they are blessed together in the restoration of Job 42.

Gregory the Great, who became Pope in 590 CE, had a less favourable view of Job’s wife, considering her Satan’s ladder to her husband’s mind. His colossal and highly-influential work, Moralia in Job, written in the years c.578–91 CE, became a quasi-Bible in itself during the Middle Ages. A depiction of Job and his wife in this eleventh-century Italian manuscript of the Moralia—made for Bishop Gunther of Bamberg—portrays him covered in sores, his torso bare and grey with ash (2:8, 12). A yellow linen cloth is draped around his legs and there are bandages on his ankles. The artist does not pursue a psychological portrayal of his suffering but presents Job in a hieratic frontal pose that likens him to Christ, and by extension to the priestly role of the Church, which was Gregory’s typological emphasis. It is thus a visual statement of his significance in the history of salvation.

Job’s wife is dressed like an eleventh-century nun of the period when this manuscript was produced. She points with a didactic gesture that seems to encourage the reader to pay attention to Job, whose own upraised hand physically touches the chapter titles of Gregory’s text on the page, reinforcing this message. The artist does not demonize Job’s wife as Gregory does. Indeed, her appearance seems to commend the religious life in medieval society as a path to female wisdom.

Unknown artist

Wall paintings from St Stephen's Chapel, Westminster Palace, c.1355–63, Wall painting, The British Museum, London; Donated by Society of Antiquaries of London, 1814,0312.2, © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

A Day of Disaster

Commentary by Ursula Weekes

In the heavenly council room of Job 1, God commends Job, but Satan accuses him of having a fair-weather faith: ‘Does Job fear God for naught?’ (v.9). Surely his luxurious life explains his apparent piety? It is only through the furnace of suffering that the truth will be demonstrated, so God says to Satan, ‘Behold Job is in your hand’ (1:12; 2:6).

In one day, Job loses all he has. His vast livestock and his servants are wiped out (1:15–17), but worse by far is the death of his ten children, killed by a desert storm that blows down the house where they are holding what may be a birthday party (vv.18–19).

Job’s children are depicted here in a rare artistic survival: a fourteenth-century mural fragment from St Stephen’s Chapel in the Royal Palace of Westminster. An adjacent scene shows messengers bringing news of the tragedy to Job and his wife. The children sit in a gothic stone hall with wooden ceiling beams, much like the architecture of St Stephen’s Chapel itself. The ceiling beams crash down on the children as they are feasting, causing them to bleed as they die. Satan appears in the central arch as a grinning horned devil, the orchestrator of this disaster. Their clothes are painted in the expensive pigments of vermilion and ultramarine, while the figural modelling, consistent light source, and use of perspective suggest Italian artists were among the elite painters working under the direction of Hugh of St Albans.

The chapel was begun by Edward I in the late thirteenth century as a rival to the Sainte Chapelle in Paris, but was only completed by Edward III, who commissioned these paintings between 1348 and 1363 as a visual commentary on his Christian kingship. In 1547, under Edward VI, St Stephen’s Chapel became the debating chamber of the House of Commons and was whitewashed. A fire in 1834 completely destroyed the chapel and was the final obliteration of what had been one of the greatest painted spaces of medieval England. The mural fragment, which had been saved in James Wyatt’s re-modelling of the House of Commons Chamber in 1800, is thus itself a reminder of the devastation that can occur in a day.

Wilhelm Heinrich Otto Dix :

Baby with Umbilical Cord, 1934 , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist :

Illustration from Moralia in Iob (Job) by Saint Gregory the Great, 1061 , Illumination on parchment

Unknown artist :

Wall paintings from St Stephen's Chapel, Westminster Palace, c.1355–63 , Wall painting

The Blameless Sufferer

Comparative commentary by Ursula Weekes

The prologue and epilogue of the book of Job are written in prose and offer a divine perspective, repeatedly telling the reader that Job was blameless and upright. But the poetry that dominates the book conveys his lived experience of suffering and isolation.

Why, in the mid-fourteenth century, did Edward III of England include Job as a subject for the murals of his jewel-like royal chapel in the Palace of Westminster? In the scene where Job and his wife receive messengers, they are portrayed seated side by side, every bit like a medieval king and queen. Edward III was married to Philippa of Hainault who bore him thirteen children over twenty-five years. Edward’s long reign saw devastating outbreaks of the Black Death, especially between September 1348 and June 1349, when an estimated sixty percent of London’s population died of the plague, including two of the king’s children. Around this time the mural painting of St Stephen’s Chapel began. Job, therefore, was an exemplar of Christian kingship in the face of personal and national grief caused by the painful sores of plague.

Wilhelm Heinrich Otto Dix’s painting of a Baby with Umbilical Cord resonates on multiple levels with Job’s journey of suffering. In chapter 1, Job’s response to losing everything is to remember he was born with nothing and therefore he owns nothing by right (1:25). But by chapter 3, Job is desolate. He feels utterly hedged in by God (3:23) who has become unfamiliar to him, inverting Satan’s taunt in 1:10 that the ‘hedge’ around Job is a special protection from God. Job longs for the day of his birth to be covered in darkness and wiped from history.

But Dix’s painting has a yet deeper affinity with Job. As Job’s suffering progresses beyond the despair of chapter 3, he begins to perceive the need for a mediator between himself and God. He understands this figure first as an arbitrator (9:33), then as an advocate–intercessor (16:19–20), and finally as his living Redeemer (19:25). This is why, in the fourth century, Jerome could describe Job as a prophet of Christ (Letter 53, section 8). Moreover, Job, the blameless sufferer, was seen to foreshadow the perfect innocent sufferer Jesus, who by his sin-bearing death becomes the Saviour.

In his compositional choices, Dix seems similarly inclined to make deliberate connections with the figure of Jesus. By portraying the baby from above, placed on a white cloth, he invokes fifteenth-century German Renaissance paintings of the Nativity by masters such as Hans Memling, where the Christ Child lies alone on a cloth laid directly on the ground. The experience of his son’s birth seems to prompt a meditation on both creation and incarnation. It is the kind of existential spirituality that Dix would make explicit in a 1965 interview (a year before he died):

when I was a boy, when we had Bible Study, I always imagined to myself exactly where that might have happened in my homeland. (Schmidt 1981: 269)

Just as Dix sees his baby’s struggle as somehow interlaced with Jesus’s humanity, so the early church fathers perceived Job’s suffering as a window onto Jesus’s ultimate suffering.

The Italian illuminator of the eleventh-century manuscript of Gregory the Great’s Moralia in Job, clearly considered Job a type of Christ (and by extension, and in accordance with Gregory’s emphasis, a type of the Church). This explains the similarity of his pose to images of the seated risen Jesus with his hand raised in blessing. Moreover, the scribe who wrote the text added some of the red ink used for the chapter numbers to Job’s hand, as a prefiguration of Christ’s stigmata.

The parallels between Christ and Job are many. Like Job, Jesus had three friends with him as he faced the cup of God’s wrath in Gethsemane (Matthew 26:36–46; Mark 14:32–42). Like Job’s friends, though in a different way, Jesus’s friends failed him—falling asleep and then deserting him. More profoundly, although Job may not have been sinless (we see him scrupulously making sacrifices at the beginning of the book), the story suggests that it was on account of his blamelessness that he was chosen for suffering. And in the necessity of Jesus’s death on the cross, Christians see one ‘who had no sin’ being ‘made sin for us so that in him we might become the righteousness of God’ (2 Corinthians 5:21). Looking at the cross in Job’s company, we look into the heart of human history, where justice and mercy meet and where undeserved suffering becomes the foundation of undeserved blessing.

References

Jerome. ‘Letter 53, To Paulinus’. 1989. Trans. W.H. Freemantle, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series 2, vol. 6, ed. by P. Schaff and H. Wace (Edinburgh: T&T Clark)

Mayr-Harting, Henry. 1999. Ottonian Book Illumination: An Historical Study (Turnhout: Harvey Miller), pp. .205–07

Quash, Ben. 2013. Found Theology (London: Bloomsbury), chapter 4

Schmidt, Diether. 1981. Otto Dix im Selbstbildnis, 2nd edn. (Berlin: Henschelverlag), pp. 269–70

Ticciati, Susannah. 2005. Job and the Disruption of Identity: Reading Beyond Barth (London: T&T Clark)

Commentaries by Ursula Weekes