Job 42

Opening the Doors of Perception

William Blake

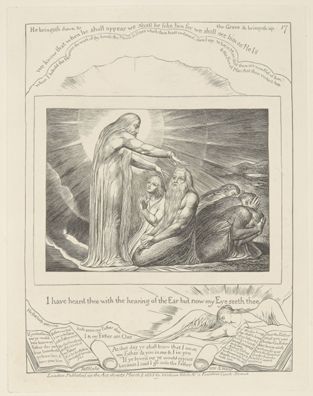

Book of Job, Plate 17, The Vision of Christ, 1825, Line engraving on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper, 384 x 276 mm, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection; B1978.43.1519, Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art

Now my Eye Seeth Thee

Commentary by Christopher Rowland

In the journey of Job to new understanding, William Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job concentrate on two climactic moments. In one, Blake imagines Job and his wife seeing God face to face (as the biblical quotations beneath indicate, this is God in Christ). In the other, Job prays for his friends. One climax is epistemological; the other is ethical. This is the first of them.

What we see in this image is a divine figure surrounded by a bright halo of light, stretching out both hands to bless Job’s wife and Job. The three comforters have their backs to this event, all with heads in hands, but with the central figure taking a surreptitious glimpse at the event taking place behind him. The backdrop, vaguely visible, is of mountains, with the glimmer of light coming on the right (east). In the margins there is little but a cumulus cloud outline, and at the bottom an angel presiding with eyes closed over open books and a scroll.

This is the crucial plate of his Illustrations of the Book of Job. It has as its main text Job 42:5, and encapsulates the way in which Blake reads the whole book. Here is exemplified Blake’s frequent contrast between ‘Memory’ (‘I have heard [of] thee by the hearing of the Ear’) and ‘Inspiration’ (‘but now mine Eye seeth thee’). It depicts the moment when, to quote the words of the Preface to Blake’s Milton, a Poem, ‘the Daughters of Memory shall become the Daughters of Inspiration’ (Erdman 2008: 95).

Blake’s understanding was profoundly influenced by the idea of the mutual indwelling of God and humanity, one of the central themes of the Gospel of John. This is evidenced in the profusion of Johannine quotations from the farewell discourses at the foot of the engraving. True insight comes from participation in God, as Job and his wife are bathed in Christ’s light.

Spiritual and mental transformation is incomplete, however, without ethical transformation. It is Job’s action in praying for his friends that will fully demonstrate his release from captivity.

References

http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3643616 [accessed 22 October 2018]

Erdman, David V. (ed.). 2008. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (Garden City: Bantam Doubleday Dell)

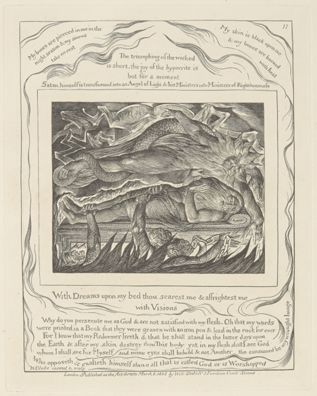

William Blake

Book of Job, Plate 11, Job's Evil Dreams, 1825, Line engraving on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper, 378 x 279 mm, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection; B1978.43.1513, Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art

Visions in the Night

Commentary by Christopher Rowland

William Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job were published two years before his death in 1827 and are in many ways a testimony to his life’s work.

In the first engraving of the series (Plate 1), Blake had chosen to show Job and his wife with books (very possibly sacred texts) open on their laps. The portrayal of Job’s subsequent experience of agony and loss then culminates here in Plate 11, with Blake imagining what Job saw in one of his dreams and visions of the night (Job 7:14).

Job sees a terrifying figure, having characteristics of the transcendent divinity depicted in earlier engravings, but entwined with a serpent who points threateningly to the law engraved on tablets of stone. Job is appalled and terrified by the threatening sight. Below are figures who would chain Job and drag him down into the fiery flames.

What seems to terrify Job is that entry to heaven consists of obedience to what is engraved on the tablets of stone (it is worth noting that in the watercolour version of this image Blake makes explicit that that it is the Decalogue which is inscribed on the stones, quoting from the Hebrew of Exodus 20:13–15), and incipient entry to hell is the consequence of disobedience. In his vision Job sees the terrifying, diabolical, character of his theology.

But by means of his night vision, Job would come to a realization of the illusory character of the theology he had received. This vision paves the way for Job to see that God is not some transcendent monster but is in Christ a divinity who is with and in him. Job declares (in words incorporated in Plate 17), ‘I have heard thee with the hearing of the Ear but now my Eye seeth thee’ (Job 42:5). It is through what Job sees, whether here in the night vision or in his vision of God (Job 38–41), that he realizes how his received theological wisdom must be turned upside down.

References

https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3643610 [accessed 22 October 2018]

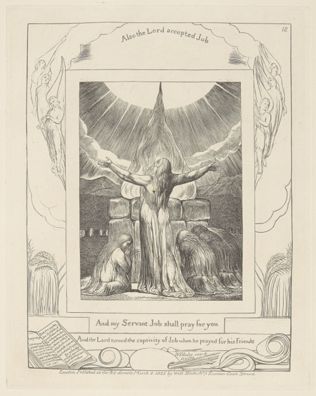

William Blake

Book of Job, Plate 18, Job's Sacrifice, 1825, Line engraving on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper, 381 x 279 mm, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection; B1978.43.1520, Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art

Turning the Captivity of Job

Commentary by Christopher Rowland

Job here stands erect for the first time in William Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job.

With his back to the viewer and arms outstretched before a stone altar, he seems to be offering sacrifice (cf. Noah and the Rainbow, Houghton Library, Harvard, B437). Above him is part of the circle of light, which had been seen surrounding Christ in the previous plate in the series. Kneeling beside the upright Job is his wife, also bathed in light, and on his right the comforters, in shade, are bowing in obeisance. The flame from the altar moves heavenward, towards the circle of light.

The words below the image are ‘And my Servant Job shall pray for you’ (Job 42:8), and above the image ‘Also the Lord accepted Job’ (Job 42:9). Blake has picked up a contrast in the text of the book of Job. The comforters are still bound by the old ways of thinking and offer sacrifice, whereas the LORD ‘turned the captivity’ of Job, when he prayed for his friends (42:7–8, 10). The emphasis in Job 42:8 echoes Romans 12:1–2 (which is not quoted in the marginal texts): ‘I beseech you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, that ye present your bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable unto God’ (KJV). The open book, with its writing, glosses the major caption. Words from Matthew 5:44–45,48 start with the exhortation to ‘love one’s enemies’ and to ‘pray for those that despitefully use you and persecute you’.

Thus, in the second of two climactic engravings, an ethical transformation complements an epistemological one, and together they confirm that Job is no longer the prisoner—and victim—of habit: ‘And the Lord turned the captivity of Job when he prayed for his friends’ (Job 42:10).

Dreams and visions have been the pathway to this. As part of his interpretative programme Blake focuses on the verses which mention them (Job 4:12–13; 32:8; 33:15). Only the visionary can disrupt the habits of religion—and of life more generally. Blake the artist and Job the recipient of visionary insight have this high and disturbing calling in common.

References

https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3643617 [accessed 22 October 2018]

William Blake :

Book of Job, Plate 17, The Vision of Christ, 1825 , Line engraving on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper

William Blake :

Book of Job, Plate 11, Job's Evil Dreams, 1825 , Line engraving on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper

William Blake :

Book of Job, Plate 18, Job's Sacrifice, 1825 , Line engraving on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper

Putting Words in their Place

Comparative commentary by Christopher Rowland

William Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job does not only offer us a unique example of the artist engaging with just one biblical book. It also—in the way it relates text to image—evinces crucial elements of features of Blake’s other illuminated books, from the Songs of Innocence and of Experience of the 1790s to Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion of the opening decade or so of the nineteenth century.

Plate 17 proclaims ‘Now my Eye seeth thee’. As in patristic interpretations of biblical theophanies (cf. John 12:41), Blake interprets the divine theophany in the whirlwind (Job 38–41) as a vision of Jesus Christ. The inclusion of passages from the Gospel of John intensifies this Christological interpretation. Job’s understanding of God has changed from transcendent and threatening monarch (who can become monstrous, as in Plate 11) to immanent divine presence: ‘At that day ye shall know that I am in my Father, and ye in me, and I in you’ (John 14:20).

Blake chose never to address Job’s words ‘Therefore I abhor myself, and repent in dust and ashes. (Job 42:6). His Job does not grovel before a transcendent deity, but as Plate 18 shows us, he is raised to his feet by his theophany. In these three engravings, we see how this is the culmination of an unfolding transformation, as Job moves from being prone in Plate 11, to kneeling in Plate 17, to standing in Plate 18. Now that his insight has been transformed, he may stand before God, and his body—like his prayers—becomes a spiritual, living, sacrifice.

In Blake’s illustrations, priority is given to centrally placed images. Plate 17 marks the moment when the contents of the books are actually seen by the reader, and we discover from the words written on the pages that the one whom Job and his wife have seen in the theophany is none other than Christ, the divine in the human. Here is the proper ordering of text and image: an ordering in which the image is given priority and the text illustrates the dominant image. The books are situated in the margins of the image and so should function as marginal comment on the images, which are central to what Blake wants to communicate. Words are now in their proper place.

Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job offers not only an understanding of one biblical book but also an insight into how the Bible as a whole should be interpreted. The book’s series of engravings move sequentially through the text, but the centrally placed images are the prime guide to its meaning.

That what is seen must be given priority is reinforced by the terrifying night vision that discloses to Job where the path of an entirely letter-based religiosity will lead. The struggle to obey the word without the illumination of the spirit brings only terror.

Blake’s alternative is to make the various and abundant biblical texts that he reproduces reflect on what is seen in the images. And it is these images that offer a key to the subject matter of the book in Blake’s estimation: a book which is about the ways in which ‘the doors of perception’ of Job are cleansed (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Plate 14).

With the book of Job as his ally, Blake’s art also offers a way of engaging with the issue of the relationship between words and images more generally. Though neither is an end in itself, words for Blake are always a complement to images. Blake did not despise discursive, diachronic reflection in words, but he absolutely prioritized the synchronic impact of an image.

Illustrations of the Book of Job thus decisively reveals the secondary place which Blake gave to the rational and the literal in the intellectual process. Priority is given to spirit, energy, desire, and above all the power of visionary imagination, in order to enable other perspectives on life. The series as a whole thereby exemplifies Blake’s deep conviction about what is ‘shewn in the Gospel’, for (as he observes) Jesus ‘prays to the Father to send the comforter or Desire that Reason may have Ideas to build on’ (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Plate 6).

References

Butlin, Martin. 1981. The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Erdman, David V. (ed.). 2008. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, (Berkeley: University of California Press), pp. 35, 39.

Lindberg, Bo. 1973. William Blake’s Illustrations to the Book of Job (Åbo Akademi)

Paley, Morton D. 2003. The Traveller in the Evening: The Last Works of William Blake (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Rowland, Christopher. 2010. Blake and the Bible (Yale University Press)

Tannenbaum, Leslie. 2017. Biblical Tradition in Blake’s Early Prophecies: The Great Code of Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Commentaries by Christopher Rowland