2 Corinthians 3:1–11

Letter and Spirit

Ugolino Marini Gibertuzzi of Sarnano

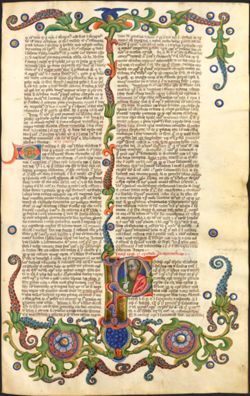

2 Corinthians, from Nicholas of Lyra's Commentary on the Bible, 14th–15th century [finished 1402], Illumination on vellum, 440 x 272 mm, John Rylands University Library, The University of Manchester; Latin MS 31 v.3 fol. 112r, The University of Manchester

Illuminating the Letter

Commentary by Naomi Billingsley

The Latin illuminare means ‘to light up’. This is the origin of the term ‘illumination’ when used to refer to the illustrations that decorate manuscripts such as this one. The biblical text is adorned with designs that are incorporated alongside or intertwined with the text.

‘Illumination’ refers to the brightness of the gold and other colours used in such objects, and also implies that the motifs are enlightening—that they reveal something about or beyond the text that might not be conveyed (or communicated as easily) by the unadorned text.

In 2 Corinthians 3, Paul contrasts the ‘letter’ of the Law of Moses with the ‘spirit’ of Christ; ‘the letter kills, but the spirit gives life’ (3:6 NRSV). This contrast does not necessitate a rejection or supersession of the Law; rather, it can be seen as analogous to the dynamic between word and image in an illuminated manuscript. The illumination does not replace the text but lights it up, and in so doing can reveal aspects of its message afresh.

The page (also known as a folio) seen here is from an early fifteenth-century manuscript of Nicholas of Lyra’s biblical commentary by a Franciscan scribe, Ugolino Marini Gibertuzzi of Sarnano. This leaf has the beginning of 2 Corinthians. The illuminations include rich foliage, and two illuminated capitals (decorated letters). The large illuminated capital ‘P’ is for the start of the Epistle, and includes a portrait of Paul holding the sword of his martyrdom. While the portrait identifies the author, the foliage does not seem to relate directly to the text itself. These adornments express the preciousness of the text, both by beautifying the object, and because the time and materials involved were costly.

Nicholas’s commentary focuses on the literal sense of the Bible, as distinct from its figurative meanings (allegorical ones, for example). He discusses details such as the language and the historical context of the text. The illumination therefore introduces an element to the page that has a more excursive relationship with the ‘letter’ of the biblical text, which can be likened to the ‘spirit’ that ‘gives life’.

Mark Rothko

Interior view of the Rothko Chapel: Northwest, North triptych, and Northeast paintings, 1965–66, Oil on canvas, Houston, Texas; © Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Rothko Chapel, Houston, TX. Photo by Hickey-Robertson

Letter and Contemplation

Commentary by Naomi Billingsley

‘Letter’ of any kind is transcended in the Rothko Chapel. Conceived by founders Dominique and John de Menil as a non-denominational sacred space, the chapel was devised by architects Philip Johnson, Howard Barnstone, and Eugene Aubrey to accommodate fourteen abstract paintings by Mark Rothko.

The Rothko Chapel may be understood as embracing a new mode of expression that emerged out of religious and artistic shifts in the twentieth century. Its octagonal plan (reminiscent of Christian baptisteries), and the triptych form of three groupings of paintings (evoking Christian altarpieces), situate the chapel in an older tradition of Christian architecture and art, and help to engender a sense of the sacred. But the almost monochromatic, abstract aesthetic of the whole resists association with any particular tradition, and thus fosters the universal religious experience that the de Menils envisioned. By eschewing figurative representation, the chapel creates a space that, as Dominique de Menil described it, ‘is oriented towards the sacred, and yet … imposes no traditional environment’ (Rothko Chapel, section 3). It is a space for people of all religious traditions (and none). It does not represent the ‘letter’ of any religion but instead invites viewers to engage in a common pursuit of contemplation and stillness.

At the same time, the chapel maintains a collection of religious texts that pilgrims or visitors can read in the space. The experience of reading a text that might be familiar in this place can provoke fresh perspectives on that text; art and architecture create a space in which the pilgrim can experience an aesthetic encounter with sacred scriptures of various traditions.

This experience can be seen as analogous to the ‘spirit’ giving life to the ‘letter’ in Paul’s terms (2 Corinthians 3:1–11). The spirit, which is literally unrepresentable, pushes beyond the literal meaning of the words on the page. Rothko’s paintings, by going beyond representation, may work in this spirit. Entering the chapel (a technology-free zone) disrupts the everyday experience that is saturated with information and images; in so doing, pilgrims might ‘give [renewed] life’ to their seeing and reading.

References

Rothko Chapel, ‘About’. Available from http://www.rothkochapel.org/learn/about/ [accessed 24 August 2018]

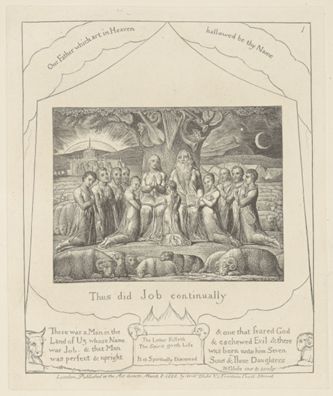

William Blake

Book of Job, Plate 1, Job and His Family, 1825, Line engraving on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper, 387 x 273 mm, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection; B1978.43.1503, Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art

Religion and Imagination

Commentary by Naomi Billingsley

‘There was a man in the land of Uz, whose name was Job; and that man was perfect and upright…’ (Job 1:1 KJV). So begins the book of Job, which the English poet, painter, and printmaker, William Blake, depicts in a series of twenty-one designs. Blake’s first Job series was produced in watercolour in c.1805–06. In 1825, he published engravings based on these designs. Here, in the first engraving, ‘The Letter Killeth The Spirit giveth Life’ (2 Corinthians 3:6 KJV) is inscribed on an altar which is depicted at bottom centre, in the margin below the main image.

In the main image, under a tree, Job and his family are engaged in prayer—some seated and others kneeling. The prayer books on the laps of Job and his wife, and the opening words of the Our Father in the margin above, suggest that they are praying with traditional liturgical texts.

Blake here rejects the idea of organized religion, believing that it stifled the individual’s engagement with the divine; for Blake, divinity is found in imagination. Blake uses Paul’s words to critique the conventional piety that Job and his family are engaged in as akin to the ‘letter’ that ‘killeth’. Blake’s Job is presented as a self-righteous man who engages in rote piety, not with imagination. This point is reinforced by the depiction of musical instruments hanging in the tree above the family, which alludes to Psalm 137:2: ‘We hanged our harps upon the willows’ (KJV). The psalm is a song of lament by the Jewish people during their exile in Babylon. By depicting instruments in the tree above Job’s family, Blake suggests that their display of conventional piety—following ‘the letter’—is a form of spiritual exile.

Tellingly, in the final design in Blake’s Job series, the artist depicts Job and his family playing the musical instruments, indicating that they now engage with ‘imagination’, or ‘the spirit’ in Blake’s use of Paul’s phrase. Thus, the series may be understood as a manifesto of Blake’s religious vision of art, encouraging the viewer to encounter the divine in the ‘life’ of imagination.

Ugolino Marini Gibertuzzi of Sarnano :

2 Corinthians, from Nicholas of Lyra's Commentary on the Bible, 14th–15th century [finished 1402] , Illumination on vellum

Mark Rothko :

Interior view of the Rothko Chapel: Northwest, North triptych, and Northeast paintings, 1965–66 , Oil on canvas

William Blake :

Book of Job, Plate 1, Job and His Family, 1825 , Line engraving on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper

Art As Spirit

Comparative commentary by Naomi Billingsley

Paul tells the people of Corinth that they are living letters, ‘written’ by Christ, embodiments of his gospel (2 Corinthians 3:1–5). ‘Letter’ here is from the Greek epistolē, meaning correspondence. Paul goes on to contrast ‘letter’ and ‘spirit’, explaining that as living epistles, the Corinthians are to be ministers ‘not of letter but of spirit; for the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life’ (v.6 NRSV). Here, ‘letter’ is from the Greek gramma, meaning writing. The letter and spirit distinction is explained in the following verses: the letter of the Law of Moses is contrasted with the spirit of Christ (vv.7–11).

Paul’s critique is not of Mosaic Law itself, but of its legalistic application that focuses on condemning sin, rather than on its broader principles. As Jesus explained when asked about the greatest commandment, the Law hangs on the commandments to love God and love your neighbour (Matthew 36:40).

Blake inscribes ‘The Letter Killeth The Spirit giveth Life’ (v.6 KJV) together with another phrase from Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, ‘It is Spiritually Discerned’ (2:14), on an altar in the margin of the opening plate of the series Illustrations to the Book of Job. Here, letter and spirit are presented as alternative means of engagement with the divine: Blake casts Job as a figure who follows the ‘letter’ of organized religion, but who lacks genuine spiritual (or in Blake’s own vocabulary, imaginative) discernment.

The final plate in the series echoes the first in many details, including the visual elements of the marginal design. Thus, the altar on which Paul’s words are inscribed at the start of the series reappears at the end of the sequence; there, it is inscribed with another phrase from Paul: ‘In burnt Offerings for Sin thou hast no Pleasure’ (Hebrews 10:6 KJV). Through his trials, Blake’s Job learns to engage with the divine not through legalistic rules and rituals, but rather through imagination, as represented in the final plate by Job and his family making music: the spirit that is more glorious than the letter (vv.7–11).

Blake’s combination of image and text in the Job series is indebted to medieval illuminated manuscripts like that of Nicholas of Lyra’s biblical commentary shown here. In Blake’s ‘illuminations’ and their medieval predecessors, the visual motifs interact with the text that they accompany in a variety of ways: sometimes illustrating, at other times in tension with, and elsewhere apparently unrelated to the text. In the example seen here, the portrait of Paul illustrates the author of the text. Although the page is the beginning of 2 Corinthians (the leaf for 2 Corinthians 3 is sparely illuminated), when readers come to the commentary on chapter 3, they might well think back to the image of Paul when he refers to himself along with the Corinthians as a living letter of Christ (vv.1–3). Paul is the living letter and so his portrait gives life to the manuscript. By contrast, the foliage bears no obvious relation to the content of the Epistle; as in almost every manuscript in the Middle Ages, such motifs appear throughout, thus creating a unified visual scheme. This apparent disjuncture between text and image is particularly striking in this manuscript because Nicholas’s commentary focuses on the plain meaning of the biblical text. The illuminations work in a different way, giving ‘spirit’ to the ‘letter’.

Fertile disruption is created in a different way in the Rothko Chapel, where both letter and (iconographic) image are eschewed. As Robert Rosenblum put it, the chapel was created to ‘inspire the kind of meditation which was elicited less and less in the twentieth century by conventional religious imagery and rites’ (Rosenblum 1975: 215). The abstract aesthetic marks the space apart from the ‘letter’ of any single religion, instead creating a place for reflection that might lead the pilgrim to a deeper or renewed understanding of the essential ‘spirit’ of the divine—analogous to the trials of Blake’s Job transforming his engagement with God from the ‘letter’ of rote religion to the ‘spirit’ of imagination.

Thus, in the three different media of a manuscript illumination, a reimagining of the book of Job in print, and a modern chapel, we see how works of art can act as spirit to the letter of religion and its texts.

References

Camille, Michael. 2018. Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art. New edn (London: Reakton)

Rosenblum, Robert. 1975. Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko (London: Thames and Hudson)

Commentaries by Naomi Billingsley