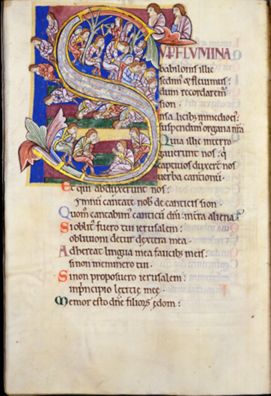

Psalm 137

By the Rivers of Babylon

Unknown English artist

Psalm 136 (Psalm 137), from St Albans Psalter, c.1119–45, Manuscript illumination on vellum, 27.6 x 18.4 cm, Dombibliothek, Hildesheim; MS St God. 1 (Property of the Basilica of St. Godehard, Hildesheim), fol. 175v, www.dombibliothek-hildesheim.de

Singing and Scheming

Commentary by W. David O. Taylor

One of the most important survivors among early English Romanesque decorated manuscripts, the twelfth-century St Albans Psalter has virtually no equal in the lavishness and refinement of its decoration, of which this letter 'S' is a prime example.

Believed to have been owned by the anchoress Christina of Markyate, the pages of this devotional and liturgical book are decorated with 215 large historiated initials. Beautifully laid out, each illustrated initial involves a compression of verbal imagery that both represents and enhances the affective character of the psalm.

Inside the ‘S’ initial that appears at the top of Psalm 137 (Psalm 136 for the monks who used Jerome’s version of the Psalms) a body of water seems to spill down the page in serpentine fashion. Filled with fish, the river-like shape symbolizes the rivers of Babylon that appear in verse 1. Elongated bodies surround the swirling initial, seated on the banks of this river. These beardless figures represent the Israelites in the garb of monks. And while most of the figures rest their chins in their hands, in an apparent gesture of sorrow (Haney 2002: 621), a few seem to call out to one another. One also holds his head in his hands.

At the top of the illuminated initial, one man hangs his harp on a tree. At the bottom, two men engage in discussion, perhaps planning retribution for the sufferings inflicted on them in their exile. This assembly of exiles, synecdoches for the children of Israel, is homesick in a foreign land. With drooped shoulders suggesting despondency, these figures sit and weep in remembrance of Zion. Some appear to lament, others to be angry. Three women are included among them. Whether listless, resigned, or in intense despair, the words of the psalmist come to life in visual form here in a company of people suffering the misery of exile. As they sit on the edge of the river, we may imagine them on the edge of despair. But they do not sit alone; they sit together alongside a river that teems with life.

References

Haney, Kristine. 2002. The St. Albans Psalter: An Anglo-Norman Song of Faith (New York: Peter Lang)

Fernando Botero

Three paintings in the Abu Ghraib prison series as displayed at the Parque Fundidora in Monterrey City, Mexico, January 2008, 2008, Oil on canvas, Collection of the artist; Photo: Simon Corral / Getty Images

The Shame of Violence

Commentary by W. David O. Taylor

In late 2003, Iraqi prisoners of war were tortured by U.S. soldiers in Tier 1A at Abu Ghraib, near Baghdad. At times beaten with broomsticks, at other times thrown wet and naked into freezing cells or coerced into performing humiliating acts, the prisoners were subjected to gruesome experiences by soldiers who captured these events on video. Prisoners were also forced to listen to loud repetitions of Psalm 137, in Boney M’s bouncy cover of the Jamaican reggae band The Melodians’ song, Rivers of Babylon.

The Colombian artist Fernando Botero, like many artists at the time of the Abu Ghraib scandal, responded to these images of abuse by making his own images—to recast the prisoners in a different light. For Botero, who created around fifty paintings in this series (Ebony 2006: 10), these images represented a visual cry against the cruelty of humanity. Borrowing from medieval Christian iconography, Botero re-presents Muslim prisoners in the figure of Christ and of the martyred saints.

This photo shows three of these paintings as displayed in the Parque Fundidora in Monterrey City, Mexico, in 2008. In each, a solitary male figure is represented, bound and hooded, in the process of being tortured. Unlike the majority of the paintings in this series, which were displayed as part of museum surveys of Botero’s work in Italy and Germany in late 2005 and early 2006, these figures’ faces remain unseen. Bound as prisoners, their bodies reveal signs of torture in their bloodied knees, shoulders, and backs while the instruments of torture are largely invisible, outside the frame.

Red hoods cover their heads, either partially or completely. Feet bound together, arms tied behind their backs with ropes, these nameless men have been stripped, rendering them further ‘undignified’ within the grids of their prison spaces.

The prisoners’ darkened cells are surrounded by other, more illuminated blocks beyond their own which further contributes to the sense of their being hemmed in.

These distant lights however may also suggest the possibility of hope—of conceivable escape from the pain in this presumed pause before the torture resumes.

References

Ebony, David. 2006. Botero Abu Ghraib (New York: Prestel)

Runions, Erin. 2014. The Babylon Complex (New York: Fordham University Press), pp. 148–78

Marc Chagall

The Western Wall ('By the rivers of Babylon we sit down and weep...'), 1966, Mosaic, 6 x 5.5 m, The Knesset, Jerusalem; © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris; Photo: The Knesset, Yitzhak Harrari

The Yearning of Exiles

Commentary by W. David O. Taylor

Born in 1887 in Vitebsk, Belarus (then the Russian Empire), to a Hasidic Jewish family, Marc Chagall is an artist who occupies multiple worlds and his works are the product of a rich combination of Jewish culture, the Bible, and Russian fairy tales with the styles and experiments of modern art.

In 1960 Chagall was invited to design and decorate the Knesset, Israel’s House of Representatives. Chagall designed twelve floor mosaics, one wall mosaic, and three Gobelin tapestries for the new building. The wall mosaic was completed in 1966, one year before the start of the Six-Day War (also known as the Third Arab–Israeli War).

Inspired by one of the subjects suggested to him by the Speaker of the Knesset at the time—Psalm 137—Chagall has no interest in a literal depiction of this curse psalm. Rather, his interest is in the creation of a symbol of the anguished heartache of the Jewish diaspora. To do so he represents the Western Wall, which at the time was under Jordanian control. But even here, Chagall’s interest lies not in an accurate depiction of the Wall but in a vision of it, a vision that would point to the end of exile. Rather than portray the reality of 1967, he designs a mosaic that suggests the yearning of exiles who, like those in Psalm 137, long to return home once and for all.

At the top right of the composition, a column of impressionistic figures appears miraculously suspended above a plaza. On the plaza, a collection of other figures huddles together. At the bottom left of the composition, a single figure leans against the Wall: a solitary symbol of hope. Against a distant horizon lie the Old City and Tower of David, symbols of strength. Floating in the centre of the composition is a menorah with golden flames, whose light illuminates the breast of the descending angel depicted above it. Blowing a shofar, the angel calls out to pilgrims far and near to return to Jerusalem. At the upper left of the composition is a Star of David in full flight, recalling the star of Numbers 24:17, pointing the way home, to Zion and the Temple Mount.

References

Amishai-Maisels, Ziva. 1973. Tapestries and Mosaics of Marc Chagall at the Knesset (New York: Tudor Publishing Company)

Unknown English artist :

Psalm 136 (Psalm 137), from St Albans Psalter, c.1119–45 , Manuscript illumination on vellum

Fernando Botero :

Three paintings in the Abu Ghraib prison series as displayed at the Parque Fundidora in Monterrey City, Mexico, January 2008, 2008 , Oil on canvas

Marc Chagall :

The Western Wall ('By the rivers of Babylon we sit down and weep...'), 1966 , Mosaic

Worship and Violence

Comparative commentary by W. David O. Taylor

The movement of Psalm 137 reads like the movement of anger: from remembrance to resolve to retribution. In the first movement, an experience of violence, suffering, and loss is recalled. ‘By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down and wept, when we remembered Zion’ (v.1). In the second movement, the pain that this experience has caused turns into a resolve to resist. ‘How can we sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land?’ (v.4). They cannot; they will not. In the third movement, the desire for retribution becomes concrete. A God of vengeance is entreated, a revenge fantasy takes shape, and a monstrous word is uttered: ‘Happy shall he be who takes your little ones and dashes them against the rock!’ (v.9).

While the first two sections of Psalm 137 have generated vast numbers of artistic settings, the third section has been largely excised from liturgical repertoires throughout church history. Both Augustine and Benedict allegorize the psalm, while Isaac Watts excludes it from his 1719 hymnal, because he felt it to be ‘opposite to the Spirit of the Gospel’ (Stowe 2016: 140). But such psalms, argues the Croatian-born theologian Miroslav Volf, ‘may point to a way out of slavery to revenge and into the freedom of forgiveness’ (1996: 124). What our three images do for us, more particularly, is invite us to see what we might all too readily wish to suppress or ignore.

In the St Albans Psalter, corresponding to the first section of Psalm 137 (vv.1–3), a group of figures most obviously appear to us as mourners. Less obviously, these figures converse with or sing to one another.

These depictions of Jews in exile may invite those who view them—including the Benedictine monks who first used this Psalter within the liturgical context of their abbey—to identify with them in certain respects. The figures could be singing, though not the song their captors requested (‘one of the songs of Zion’) but an angry rebel song. Viewing this image, the monks might be reminded of the liberating power that comes from singing one’s laments and that their own Christian journey was one that intensified their longing for a heavenly home which meant, in spiritual terms, they still had far to travel.

The Psalter as a whole ends with a diptych representing St Alban’s martyrdom and David the cheerful musician, suggesting to the reader the common end of the saint and of the Psalter, namely joy. But as with Psalm 137, violence and worship are placed side by side, perhaps as a reminder to the reader that faithful worship does not exclude the harsh realities of life.

In Marc Chagall’s mosaic, which I link here to section two of Psalm 137 (vv.4–6), a juxtaposition of war and peace, power and powerlessness occurs. While the liturgical setting of St Albans contextualizes the Psalter’s illuminated initial, in the case of Chagall’s work it is a geographic setting that supplies a possible context for interpretation. Created a year before the start of the violent Six-Day War, the mosaic envisions a day of peace. Designed for a building in which powerful individuals gather, the mosaic shows only a powerless people, a people who at the time of Chagall’s work were barred from the area of the Western Wall. Symbolizing Israel’s longing for home, the mosaic’s location in the Knesset represents the fulfilment of the longing of exiles. Chagall’s mosaic exists therefore in a conjunction of tensions and conflictive meanings, and thus plunges the viewer more deeply into the awful tensions of Psalm 137.

Fernando Botero’s paintings, which seem to echo the third section of Psalm 137 (vv.7–9), help the existential setting of this imprecatory psalm take centre stage for us. The images, some visually recalling an Ecce Homo, show us what it looks like to suffer ignominiously but to retain a measure of dignity. But Botero’s paintings may also confront us with our own tendencies to violence, whether aggressive or passive. Rather than leave us in the safe place of the ‘good guy’ or the ‘innocent one’, the paintings could be placing us in the position of the tormentor, revealing what we are capable of when our angers turn bloodthirsty and barbaric. Everyone, the image insists, is potentially a victim, potentially a perpetrator.

Could I be this cruel? Yes, these images suggest, in the right circumstances, I could. Will I be undone by my experiences of suffering? By God’s grace, no. Is there a safe place for my anger? Yes, in the face of God who both loves and does justice, and only there.

References

Stowe, David W. 2016. Song of Exile: The Enduring Mystery of Psalm 137 (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Volf, Miroslav. 1996. Exclusion and Embrace (Nashville: Abingdon Press)

Commentaries by W. David O. Taylor