Psalm 139

Darkness Illuminated

Mordechai Beck

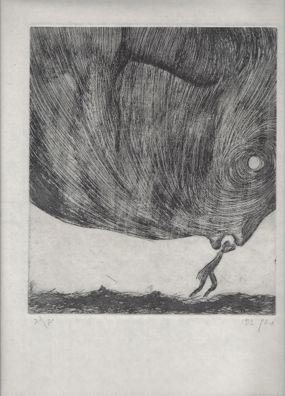

Print from Maftir Yonah (The Book of Jonah), 1992, Etching and aquatint on hand made paper, called Abacus, produced for the edition by Izhar Neumann at the Tut-Neyar Paper Mill, Zichron Ya'akov, 215 x 185 mm- size of etching on page, David Moss (calligrapher) [California: Bet Alpha Editions, 1992]; Mordechai Beck, David Moss © Bet Alpha Editions

Suppose Jonah Is Speaking…

Commentary by Ellen F. Davis and Makoto Fujimura

Many psalms are associated with the royal house of David, and ancient tradition connects some with particular moments in that king’s life (e.g. Psalm 51). However, the first-person speech and vivid language of these prayers is capacious enough to make room for other lives and stories. Suppose, then, as an imaginative experiment we hear the prophet Jonah as the speaker here:

Where can I go from your spirit [ruach]?

Or where can I flee from your presence? (Psalm 139:7)

The Hebrew word ruach denotes ‘spirit’ and ‘wind’, and Mordechai Beck’s etching suggests both. When God’s speaking spirit overshadows Jonah, it is a stormwind. Swirling darkness spies him out in flight and threatens to suck him in. He raises a tiny arm in a futile attempt to ward off God’s overwhelming presence:

You hem me in, behind and before. (v.5)

This psalm is honest enough to admit that at least in its early stages, intimacy with God is often too close for comfort. Yet the speaker also relies on that inescapable nearness and ultimately claims it as a source of hope: ‘Lead me in the way everlasting’ (v.24).

In its praise of God’s wonderful works (v.14), this psalm goes beyond any words the book of Jonah records for that disgruntled prophet. Nonetheless, it is intriguing to think that in the latter verses of the psalm we might catch another echo of Jonah, sitting dissatisfied outside the walls of the Assyrian capital, Nineveh (see Jonah 3–4). Angry that God has spared the empire that destroyed ten tribes of Israel, he is still trying to win God over to his way of seeing things:

Do not I hate those who hate you, O Lord?

And do I not loathe those who rise up against you? (v.21)

The book of Jonah itself is an open-ended conversation. How will God respond to that provocation: with the vengeance Jonah seeks, or mercy on all God’s works?

Makoto Fujimura

Psalm 139: All Saints Princeton Liturgical Altarpiece Series (Diptych), 2020-21, Mineral pigments on canvas, 121.9 x 365.8 cm, All Saints Princeton Church Liturgical Panels, Lenten Season; ©2020MakotoFujimura

Bright Abyss

Commentary by Makoto Fujimura and Ellen F. Davis

My Psalm 139: All Saints Liturgical Installation is a diptych that was installed in All Saints Episcopal Church in Princeton in Lent 2022. The two large canvasses spanning 12 feet (3.65 metres) are layered in refractive, prismatic colours using ancient Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) mineral pigments on modern gesso.

Although the work appears dark on screen, it is conceived as what the poet Christian Wiman calls ‘My Bright Abyss’. It brings moody layers evocative of Mark Rothko’s paintings into the light of present wonder and praise, to sing with the psalmist, ‘I am fearfully and wonderfully made’ (Psalm 139:14).

Psalm 139 was one of the first Bible passages I studied as a young artist. It transcends the limits of time, giving us a glimpse of God’s sovereignty experienced (though perhaps not recognized) from our earliest days (vv.13–16), even as God’s anticipatory knowledge and prevenient grace accompany us in the present (vv.2–12), and the Spirit invites us to co-create towards the new creation (vv.16, 23–24). The psalm is a response to the mystery of God’s knowing, and to this artist, its expression of depth and power was a point of entry to the Bible as a sacred text that provides both personal redemption and future hope.

The All Saints Liturgical Installation is placed on the white walls of the sanctuary in Princeton, pointing through clear windows to the forest beyond. Each panel is meant to recede into the space behind the altar and choir, making breathing room for the drama that activates the chancel. Layers of refractive minerals and gesso draw the viewer into contemplation, inviting them into the silent, ‘slow art’ that opens our senses—in this case, for Lenten reflection.

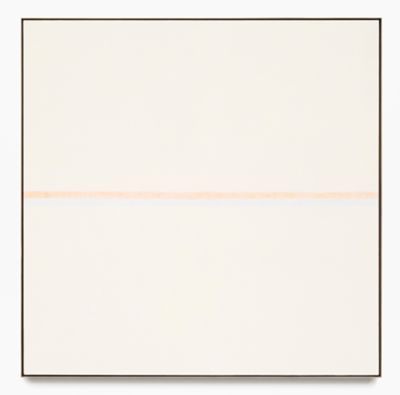

Agnes Martin

Happiness, 1999, Acrylic and graphite on canvas, 152.4 x 152.4 cm, Dia Art Foundation, New York; Partial gift, Lannan Foundation, 2013, 2013.014, © Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York; Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York, courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

Simple Joy

Commentary by Ellen F. Davis and Makoto Fujimura

In Happiness, Agnes Martin layers strokes of paint joyfully yet with careful nuance. The painting is punctuated by the single horizontal ribbon of a line halfway down the canvas, which suggests a vista. It is as if we are looking at the horizon of the New Mexico desert, experienced with an intensity that borders on the ecstatic.

Martin’s work can evoke a ‘near death’ perspective, perhaps even seeming to cross the threshold from life to death, and then from death to life. The love-filled lines in all of Martin’s works are precise as a surgeon’s knife, cutting through malaise, or psyches paralyzed by ennui. She might be inscribing the psalmist’s awe:

How weighty to me are your thoughts, O God!

How vast is the sum of them! (Psalm 139:17).

One of the great mystics of our time, Martin writes eloquently of her own desert exile, literally and figuratively. After establishing her career to acclaim in New York City in the 1960s, she gave away her possessions, including her painting supplies, and went on a long journey, eventually building a home in New Mexico, where she wrote and, seven years later, returned to painting. She identified beauty as ‘the mystery of life’ and ‘our positive response to life’. ‘Beauty and perfection are the same’, she stated; ‘[t]hey never occur without happiness’ (Campbell 1989). Such a statement might seem startling to hear from someone who operated for over fifty years in an art world that can often seem cynically focused on wealth and celebrity.

Now her works are honoured with their own dedicated space. The Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco has given them a semi-permanent ‘chapel’ at the end of the contemporary art wing, where they invite deeper introspection, even prayerful reflection, on the interconnection of beauty and happiness in response to God’s perfections. Psalm 139 is a perfect companion to her humble, joyful work:

Such knowledge is too wonderful for me;

it is so high that I cannot attain it. (Psalm 139:6)

References

Campbell, Suzan.1989. ‘Oral history interview with Agnes Martin, 1989 May 15’, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, available at https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-ag…

Mordechai Beck :

Print from Maftir Yonah (The Book of Jonah), 1992 , Etching and aquatint on hand made paper, called Abacus, produced for the edition by Izhar Neumann at the Tut-Neyar Paper Mill, Zichron Ya'akov

Makoto Fujimura :

Psalm 139: All Saints Princeton Liturgical Altarpiece Series (Diptych), 2020-21 , Mineral pigments on canvas

Agnes Martin :

Happiness, 1999 , Acrylic and graphite on canvas

The Way Everlasting

Comparative commentary by Ellen F. Davis and Makoto Fujimura

There is no getting away from God’s constant presence and penetrating knowledge. That reality dominates this psalm; it is the sum of the psalmist’s reality. But is this inescapability of God good news or bad, torment or encouragement? The psalm does not compel a single, unambiguous answer to this question, for it speaks to the devout reader in different and contrasting tones: humble awe at God’s inexhaustible knowledge of me; a sense of constraint, even frustration at the divine hand that ‘hem[s] me in’ (v.5); delighted wonder at my own created form; ‘perfect hatred’ (Psalm 139:22) of the enemies of God. We have chosen or created three works that evoke some of its tones; together they gesture toward the paradox of distinct moods that nonetheless merge with and emerge from each other.

For one of us—Mako, when a young artist—Psalm 139 was a gateway into Scripture and faith. Indeed, it offers a rare depiction of God as artist, overseeing the gorgeous craftwork that happens in the womb: weaving, astonishingly intricate (v.15). Each of us is one of God’s creative thoughts, weighty and innumerable as sand (vv.17–18). Yet like sand, every grain is distinctive precisely in its brokenness. Our lives refract light, like the azurite paint applied here in dozens of layers. Thus, the diptych is a painted poem of light shining in darkness. The darkness does not disappear, nor even lose its depths. Rather, it becomes penetrable by God, like the psalmist’s own being: ‘Darkness is as light to you’ (Psalm 139:12).

The dark spot at the top of the left-hand panel is the genesis point for the painting. When Mako began, dripping water spontaneously pushed the dark paint out, creating a halo around it, and he followed its flow. The result is a meditation on mysteries hidden in a universe too vast for humans ever to know, and yet the luminous presence behind the mysteries is intimately involved with each of us. This is ludicrous, the laughable truth that makes life possible when darkness threatens to swallow us: ‘The night is as bright as the day’ (v.12).

In Mordechai Beck’s etching of Jonah ‘on the run’—fleeing from God—divine presence is palpable as looming, living darkness, like the ‘great wind’ [ruach] that God will soon ‘hurl’ at the sea to block his escape (Jonah 1:4). Beck portrays the prophet in a world that has been drastically simplified, like the psalmist’s world—reduced, or elevated, to the bare encounter with divine presence: ‘…you are there’ (Psalm 139:8). Yet at the moment Beck highlights, God’s immediacy is felt not as promise or radical possibility, but as sheer demand, unwelcome and likely not survivable.

By contrast, sheer possibility is what Agnes Martin’s pale canvas can seem to convey. The application of many dilute layers of softly coloured paint gives the surface a shimmer that responds to changing light conditions. Martin’s affinity for such luminous canvases has been called ‘her weapon of regeneration’ on behalf of art and the world itself, wielded against the stark denial evinced by the lightless work of some of her contemporaries (Fer 2015: 172–81).

Yet possibility is not mere fantasy. Two subtle but distinct lines are drawn firmly across the large canvas. They provide a place to ‘move along step by step’, as Martin described the life of the painter, as we grow in awareness of the realities of the human condition, which she identified simply as happiness (Popova 2020).

A common Hebrew verb meaning ‘to wait in expectation/hope’, one which appears often in the Psalms (e.g., Psalm 27:1; 40:1—the NRSV translation of the verb in these lines as ‘wait patiently’ is misleading), is q-v-h, derived from the noun qav, denoting a straight line. To wait on God is to trace a line of possibility stretched taut between what God has already done and what God has yet to do. Moving along that line of possibility is the stable but not static condition of happiness as we can know it in this world. Our psalmist calls it ‘the way everlasting’ (Psalm 139:24).

References

Fer, Briony. 2015. ‘Who’s Afraid of Triangles?’, in Agnes Martin, ed. by Frances Morris (Tate Modern: London)

Popova, Maria. 2020. ‘Beloved Artist Agnes Martin on Our Greatest Obstacle to Happiness and How to Transcend It’, www.brainpickings.org [accessed 12 July 2021]

Commentaries by Ellen F. Davis and Makoto Fujimura