Job 38

Out of the Whirlwind

Works of art by Ivan Ayvazovsky, Unknown artists (Marianos and his son Hanina) and Unknown Ethiopian artist

Unknown artists (Marianos and his son Hanina)

Beth Alpha Synagogue Mosaic, 6th century, Mosaic, Beth Alpha, Israel; The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

An Ironic Reproof

Commentary by David Emanuel

The Beth Alpha synagogue, just west of the Jordan River, houses an impressive array of mosaics, one of which—a zodiac circle—lies on the floor at the centre of the synagogue.

The mosaic’s hub displays the sun god, Helios, flanked by two horses on either side. Circling the image of Helios are depictions of the twelve signs of the zodiac. Each segment holds the zodiac sign together with its Hebrew name. Located in the four corners of the mosaic are personifications of the four seasons: Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter.

Undoubtedly, the Jewish community at Beth Alpha was well versed in the sun’s and moon’s movements in the sky, and at least a thousand years earlier, the biblical figure Job clearly bore a similar knowledge of astral bodies and their courses.

In Job 38:31–33, God questions Job concerning his role, or lack thereof, in ordering the stars and constellations in the night sky. He questions Job concerning the Pleiades, a cluster of stars in the shoulder of Taurus the bull—the second segment moving clockwise from the top. Furthermore, God inquires whether Job can ‘loose the cords of Orion’, the hunter, depicted as the archer in the mosaic—the fifth segment of the zodiac mosaic, moving anti-clockwise.

The subtle irony of divine questioning in Job 38:31–32 is that God reuses Job’s own words to rebuke him. Earlier, in Job’s lengthy and heated discussion with his three friends—and to illustrate God’s omnipotence—Job reminds them of God’s magnificent work in creating and ordering the stars in the night sky. In doing so, he declares, ‘Who made the Bear and Orion, the Pleiades and the chambers of the south?’ (9:9). Ironically, God recalls these same constellations—and the very words of Job—to reprove him and remind him of his humble position.

References

Talgam, Rina (ed.). 2014. Mosaics of Faith: Floors of Pagans, Jews, Samaritans, Christians and Muslims in the Holy Land (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press), pp. 298–302

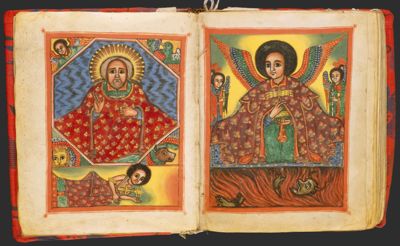

Unknown Ethiopian artist

God the Father with Donor from the Homiliary of the Archangel Michael, After 1730, Illumination on parchment, Each folio: 285 x 230 mm, The Church of the Archangelo Mikael, Ankobarr; EMML no.2373, fols 3v–4r, Photo: © 1993 Malcolm Varon, New York City

A Dramatic Reversal

Commentary by David Emanuel

The Homiliary of the Archangel Michael contains a series of illuminations dedicated to honouring the Archangel Michael in Ethiopia’s rich Christian tradition.

A depiction of God dominates the composition of folio 3v, where he is adorned with a magnificent red robe and distinguished from the other figures by rays of light emanating from his head. Unlike the angelic and human figures depicted here, the artist portrays the deity with white hair, possibly influenced by Daniel 7:9, ‘And the hair of his head [was] like pure wool’.

The heads of four living creatures surround the octagonally-framed image of God: a bird, an ox, a lion, and a winged figure (the archangel Michael, to whom the homiliary is dedicated). Together these four images (reading the face of Michael as the face of a man) recall the living creatures surrounding God’s throne in Ezekiel 1:10 and Revelation 4:7. Positioned at the bottom of the illumination we find a figure representing the homiliary’s patron, in all likelihood a ruler of some description, Fasiladis. Although he still carries his sceptre, he lies prostrate, horizontal, before the throne and the presence of God. His gaze points towards the viewer, so as to avoid looking directly at the theophany above.

Job’s demeanour and attitude in chapter 38 results from a dramatic reversal. Up until this point in the narrative, he remains confident in his own righteousness and extremely vocal in refuting the arguments and accusations of his three companions. He envisaged approaching God, ‘like a prince’ (31:37) when they met face-to-face, so he could exonerate his name.

In chapter 38, however, Job’s demeanour transforms into one very like that of the donor depicted in the homiliary. The divine presence reduces Job to silence. With his mouth closed, he can only lie prostrate before Almighty God. Just as God’s depiction dominates the homiliary’s frame, so too God’s words—his relentless interrogation and questioning of Job, beginning in chapter 38—dominate the narrative from this point onwards in the book.

References

Heldman, M. 1993. ‘The Late Solomonic Period: 1540–1769’, in African Zion: The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, ed. by R. Grierson (New Haven: Yale University Press), pp. 253–54

Ivan Ayvazovsky

Chaos (The Creation), 1841, Oil on canvas, 106 x 75 cm, Museo Armeno, Venice; Bridgeman Images

Ordering Chaos with a Spoken Word

Commentary by David Emanuel

Ivan Ayvazovsky’s depiction of creation imagines an instant in time, during the early stages of the Genesis creation account, when God is described as shaping and forming the world. The painting appears to show the moment when God utters the words, ‘Let there be light’, in Genesis 1:3. However, as opposed to the light of the sun and moon on the fourth day of creation, Ayvazovsky depicts a different light, one emanating from God himself, whose humanoid form, composed entirely of light, emerges like the sun from behind a dark cloud. This light marks the very beginning of the creation process, before God subdues the dark chaotic waters, shown at the bottom of the painting, and separates them, allowing the land to arise.

God’s spoken word in Genesis constitutes the primary means through which he fashions order from chaos, and it serves this function again in Job 38:1: ‘Then the Lord answered Job out of the whirlwind’. Here, from the depths of a storm, God’s words once again bring order, not to creation, but to the heated discussions of Job and his three friends, Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar.

Throughout the book, Job’s three companions all adhere strictly to the principle of retribution: God unfailingly blesses those who are righteous and punishes sinners. Consequently, they view Job’s physical ailments as resulting directly from divine wrath levelled against him on account of concealed sins in his life.

Job, on the other hand, vehemently protests his innocence, demanding an audience with God so he can vindicate himself in person (23:3–7). The ever-increasing tension from the back-and-forth arguments concerning the character and justice of God ends in chapter 38 because at this point God himself enters the fray, speaking on his own behalf. The verbally chaotic argument between Job and his companions abruptly ends, as God settles the dispute, silencing the incorrect perceptions of his character and justice portrayed by Job and his companions.

References

Chilvers, I. (ed.). 2004. The Oxford Dictionary of Art, 3rd edn. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 12

Tsevat, M. 1996. ‘The Meaning of the Book of Job’, Hebrew Union College Annual 37, pp. 73–106

Unknown artists (Marianos and his son Hanina) :

Beth Alpha Synagogue Mosaic, 6th century , Mosaic

Unknown Ethiopian artist :

God the Father with Donor from the Homiliary of the Archangel Michael, After 1730 , Illumination on parchment

Ivan Ayvazovsky :

Chaos (The Creation), 1841 , Oil on canvas

A Lesson for the Ages

Comparative commentary by David Emanuel

In Isaiah 55, the prophet prophesies future blessings that God will bestow on his people. As part of his proclamation on behalf of God, Isaiah declares:

For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts. (Isaiah 55:9)

Through this declaration, God explicates the incomprehensible and unbreachable gulf that exists between himself and humanity, Creator and creation. They differ in just about every imaginable facet: knowledge, lifespan, strength, and much more besides.

Job 38, together with the remainder of the book, reiterates this fundamental truth. In Job’s objections to his three friends, as they argue concerning his sin and righteousness, Job behaves almost as though God were just another one of his comforters, a man. He boldly invites God, the Creator of the world, to respond: ‘Oh, that I had one to hear me! (Here is my signature! let the Almighty answer me!)’ (Job 31:35). When God finally confronts Job, speaking to him from the storm (38:1–2), the overall tenor and purpose of the divine words inculcate the superiority of God over humankind. God poses a series of rhetorical questions to Job, to recall, emphasize, and reinforce his dominion over Job.

Each of the three artworks in this exhibition highlights various nuances of God’s pre-eminence over Job, and indeed all humankind.

Ivan Ayvazovsky depicts God at the earliest stages of his creative work. Recollection of this absolute originating power is at the heart of God’s speech from the whirlwind, and brings home his absolute superiority over Job with respect to time. The painting presents us with a lone individual figure—God—whose shining form hovers above the dark cloud in the centre. No other signs of life appear, not even the heavenly bodies—sun, moon, and stars. The work, therefore, reinforces the message of Job 38:4: ‘Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?’. God was alive and active long before the creation of humankind—and, indeed, before time itself. Although the precise length of Job's life is not stated in the book, we can be sure that his life was finite (he died ‘full of days’; Job 42:17). God, on the other hand, existed before the creation of the world and is not bound to the restrictions of time like the rest of creation.

The Beth Alpha mosaic depicts the constellations—the combinations of stars in the sky that change position, according to human perspective, coursing their way across the heavens as the months and years pass. Recollection of the vast array of stars and planets in their diverse configurations highlights the spatial disparity between God and Job. From his vantage point on earth, Job could see the constellations without any true knowledge of their actual size and the unfathomable distance they were from the earth. God, on the other hand, not only knows their size and distance from the earth, but further bears sole responsibility for their creation and placement in the night sky. That which Job could barely see and describe, God has created and ordered. The Beth Alpha mosaic thus reiterates God’s superiority over Job with respect to space.

Finally, the Homiliary draws attention to the vast differences between Job and God regarding regal status. Within the composition—if we imagine Job in the position of the donor—numerous factors contribute to this perception. Compositionally, God’s preeminent status is reinforced as he towers over the human figure. Spatially, God dominates the page, a majestic robe surrounding him. His face radiates light. Contrasting with this splendour of divine majesty, the human subject lacks any royal regalia, appearing without even clothing for his upper body. Additionally, the artist portrays him horizontal, prostrate, and occupying a marginal space on the page. God is a majestic and almighty king, and the Job-like donor reflects an insignificant and humble part of his creation—a mortal man.

In the present age of rapid technological advances and global communication, all manner of information literally resides within arm’s reach. Just about every query or question we need answering quickly becomes available through a well-phrased internet search. Despite humanity’s increased access to facts, statistics, and information, the questions God poses to Job in chapter 38, overall, remain unanswerable. Consequently, the messages reinforced by the three artworks in this exhibition remain as relevant to today’s society as they were for Job: for as high as the heavens are from the earth so are God’s ways higher than our ways.

Commentaries by David Emanuel