Genesis 14:1–17

Abram the Warlord

Unknown, Region of Lake Constance

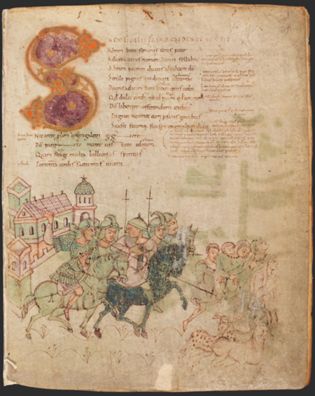

Lot Taken Captive by the Army of the Four Kings, from Prudentius, Carmina, c.900, Illumination on parchment, 273/283 x 215/220 mm, Burgerbibliothek, Bern; Cod. 264, fol. 31r (p.61), Digital Colorchecker – Prudentius, Carmina (https://www.e-codices.ch/en/list/one/bbb/0264)

Sacking Sodom

Commentary by Michele Luigi Vescovi

This illumination presents the poignant moment when the army of the four kings from Mesopotamia, after seizing Sodom, are taking away the inhabitants and their goods (Genesis 14:11–12). The manuscript was probably produced at the beginning of the tenth century in the area of Lake Constance (Reichenau), and illustrates the Prologue of Prudentius’s Psychomachia, a sixth-century poem narrating the fight between virtues and vices. Between the ninth and the tenth centuries, glosses were added to Prudentius’s text to clarify and comment upon its allegorical meanings. In this manuscript, the glosses in the right margin explain that the kings represent the vices, and Abraham the fight against evil.

The folio is divided into two parts. While the upper section contains the first fourteen verses of the Psychomachia (and some glosses), the lower part visualizes and comments upon the biblical narrative. Five soldiers, riding their imposing horses, have just left Sodom. The city, enclosed by crenellated walls with angular towers, appears abandoned but not destroyed. The soldiers drive the captives (including Lot) from the city, tormenting them with their lances. Below the captives, animals represent the food and possessions seized by the conquerors.

The artist enhances the pathos of the story through a juxtaposition of facial expressions, showing us the resigned attitude of the prisoners, the mute dialogue of the soldiers, and the ruthless expression of the horses. Some of the kings are depicted wearing scale armour and conical helmets, whose representation occurs more frequently in Byzantine manuscripts (Coupland 1990: 30–31). Through the depiction of exotic elements, the artist might have been referring to the relatively remote geographical provenance of the army.

This illuminated page has many different layers of meaning. On the one hand, it presents the biblical narration of Lot taken captive by the conquerors. On the other, Prudentius’s text and its glosses invite the viewer to explore the deeper allegorical significance of the scene: the kings represent the senses, and here Lot is subjugated by them. In this way—by extension—the battle of Abram represents an ongoing, life-and-death battle against sin.

References

Coupland, Simon. 1990. ‘Carolingian Arms and Armor in the Ninth Century’, Viator, 21: 29–50

Unknown artist

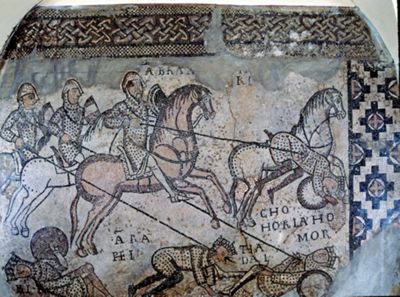

Abraham Defeating the Four Kings, c.1150, Mosaic, Casale Monferrato Cathedral, Italy; Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

How Are the Mighty Fallen!

Commentary by Michele Luigi Vescovi

This scene is part of a large floor mosaic, whose elements were discovered in the second half of the nineteenth century in the choir of the parish church of Casale Monferrato (now the Cathedral). It represents the moment implied in the text in which, following Lot’s captivity, his uncle Abraham (then still Abram) and his army reached and killed the four kings (Genesis 14:14–15).

At the centre of this fragment, Abram, identified by an inscription, is leading his handpicked men, here represented by the two figures riding behind him. All three wear mail shirts and semi-circular helmets and are in the act of spearing the kings with their long lances. Chedorlaomer (identified in the inscription as Chohorlahomor), wounded, is shown falling from his horse, while the other kings are already lying on the ground. The Mesopotamian kings are identified by their names and by the crowns on their heads. They are all equipped with circular shields.

The rest of the floor mosaic included other scenes from the Old Testament, such as Jonah and two episodes of the book of the Maccabees, in addition to exotic animals and different populations of the earth. The interpretation of these scenes is still open to discussion. They might represent the battle between virtues and vices. They might also have a different rationale. During the twelfth century, the Maccabees were usually associated with the idea of Crusade, and the battle between Abram and the four kings took place near Damascus (Genesis 14:15, the first occurrence of this city in the Old Testament). Furthermore, the juxtaposition of this scene with the story of Jonah may also relate to the Crusades. As the Prophet was sent to preach in Nineveh (Upper Mesopotamia) by God himself (Jonah 1:1), so also one of the crusaders’ aims was to win souls.

The production of this floor mosaic is likely to have followed the Second Crusade, in which inhabitants of Casale took part and which ended with the failed siege of Damascus (1148). Showing biblical protagonists dressed and armed as twelfth-century knights, and displaying both biblical victories (Abram) and defeats (Maccabees), the mosaic imagery made these narratives vividly relevant to the contemporary experiences of the town’s citizens (Vescovi 2016: 117–124).

References

Vescovi, Michele Luigi. 2016. ‘Framing the civitas: Sant'Evasio at Casale Monferrato’, in Dalla Res Publica al Comune: uomini, istituzioni, pietre dal XII al XIII secolo, ed. by A. Calzona, G. M. Cantarella (Verona: Centro Studi Leon Battista Alberti), pp.111–128

Master of Abraham

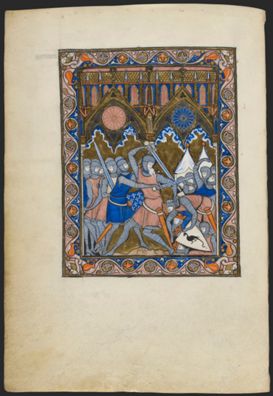

The Victory of Abraham over the Four Kings, from Psautier dit de saint Louis, 1270–1274, Illuminated manuscript, 205 x 150 mm, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Paris; Latin 10525, fol. 5v, Bibliothèque Nationale de France ark: / 12148 / btv1b8447877n

An Allegory of Royal Victory

Commentary by Michele Luigi Vescovi

The illumination appears in the ‘Psalter of St Louis’. It is a sumptuous illuminated manuscript produced in the mid-1260s for the Crusader king of France. Seventy-eight full-page miniatures depict episodes from the Old Testament, followed by a liturgical calendar and the Psalms. The depiction of the battle of Abraham (still Abram at this point) is preceded by the drunkenness of Noah (Genesis 9:20–27; fol. 4r) and followed by the encounter between the patriarch and Melchizedek (Genesis 14:17–24; fol. 6r).

The scene here of the defeat of the four kings, enclosed within a foliate frame, is identified by an inscription on the recto of the folio. A gothic building with buttresses, pediments and rose windows provides the background of the action. The image is densely populated: at the centre is Abram, taller than the other figures, with a long, bifurcated white beard. He is holding the head of one of the kings, ready to impart the fatal blow with his long sword. The other kings, identified by their crowns, have already been killed, as well as many of their soldiers behind them. In the background, white tents identify the camp where the kings have been surprised overnight by Abram’s attack (v.15). Two shields are visible in the forefront, one, on the right, presents the threatening symbol of a black dragon, while the other, immediately behind Abram, is decorated with white fleur-de-lis, the coat of arms of the royal house of France.

The shield emphasizes the relevance of this scene in a private, royal psalter. The pseudo-Capetian arms (of the dynasty that ruled France since 987) suggests that this is an allegory of royal victory: even though Abraham was not a king, he is ‘the founder of that nation from which all Christian royalty derives’ (Stahl 2008: 171). Thus he is someone with whom a medieval Christian monarch, both bellicose and devout, would be keen to identify.

References

Stahl, Hervey. 2008. Picturing Kingship: History and Painting in the Psalter of Saint Louis, (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press)

Unknown, Region of Lake Constance :

Lot Taken Captive by the Army of the Four Kings, from Prudentius, Carmina, c.900 , Illumination on parchment

Unknown artist :

Abraham Defeating the Four Kings, c.1150 , Mosaic

Master of Abraham :

The Victory of Abraham over the Four Kings, from Psautier dit de saint Louis, 1270–1274 , Illuminated manuscript

Carnality, Crusade, and Conquest

Comparative commentary by Michele Luigi Vescovi

Genesis 14:1–17 narrates episodes from the story of Abraham (here still Abram), following his expulsion from Egypt and his relocation in the land of Canaan. The narrative opens with a military conflict, in which, after twelve years of submission, five kings of the cities in the area of Sodom and Gomorrah (near the Jordan river) rebel against the ruling group of four kings of the region of Babylonia (v.4). The four ruling kings from Mesopotamia, after a successful campaign, break into Sodom and Gomorrah, seizing goods and food, and taking captives, including Lot, Abram’s nephew, who was living in Sodom (vv.11–12; c.f. Genesis 13:11–13). Alerted to the event, Abram gathers several hundred men and attacks the army overnight, recovering and bringing back Lot, his possessions, and the prisoners (vv.13–16).

The episode was of crucial importance in medieval biblical commentaries. Indeed, Prudentius opens his Psychomachia (c. 405)—probably the earliest and most influential medieval allegorical poem, describing the conflict of vices and virtues—with the battle of Abram. As allegory, the episode serves as a Christian model of how to have faith and to be freed from the ‘foulness of desire’. It is not a matter of coincidence that the capture of Lot which constitutes the inception of Prudentius’s narration takes place in Sodom, as the inhabitants of that city have already been defined in Genesis as ‘wicked, great sinners against the Lord’ (Genesis 13:13).

In the tenth-century illumination, the army has already left Sodom, the walled city on the left, carrying with them their booty: food, animals, and prisoners, including Lot. The glosses added to Prudentius’s poem explain that Abram signifies the spirit fighting against evil, while the kings are connected to the senses to which human beings are subjugated.

But while virtue is here shown in bonds, it will soon appear in armour. The story of Abraham is a progression to inner purity, in which the ensuing battle with the kings is extremely significant (Hanna 1977: 110). Saint Ambrose of Milan (c.340–97) suggests that ‘the four kings are bodily and worldly enticements’, while Abram is ‘a trained mind which has received the true wisdom’ and by recovering Lot’s possessions he restored in him ‘the vital substance of the soul’ (Saint Ambrose of Milan 2000: 70–71).

The mosaic from the floor of the parish church of Casale Monferrato (c.1150), was once part of an extensive cycle showing other scriptural scenes. Viewers walking in the church would not only have been able to see Abram, dressed as a twelfth-century knight, chasing and killing the four kings from Mesopotamia. Around it they would also have seen Jonah and two episodes from the history of the Maccabees. Thus, the meaning of this particular scene would have been enhanced by its juxtaposition with other episodes, probably through their common connection to the experience of the Crusades. In contemporary preaching, the Crusade was described as an opportunity presented by God to a generation in need of personal salvation, thus emphasising (as in Ambrose’s writings) the battle as a spiritual journey (Phillips 2007: 61–98).

The third example appears on the parchment of the royal psalter made for King Louis IX (c.1260). The same scene, Abram killing the kings, is represented differently from Casale Monferrato’s mosaic, as now the patriarch, imposing in stature, is fighting on foot rather than riding a horse, raising his sword, and ready to impart the final blow. The floor mosaic and the illuminated manuscript could hardly have been more different in terms of their visibility, their accessibility, and the media in which they realized this same biblical episode. Nevertheless, both works subtly address their audiences as meditative tools. In the illuminated page there appears the fleur-de-lis, the coat of arms of the king of France. Thus, Abram is here exceptionally represented as a king (even though he never had this title). Moreover, the inclusion in the work of the royal arms emphasizes a direct link between the patriarch and the French monarch, inviting its viewer not only to consider the allegorical meaning of the scene, but also Abram as the model of royal victory. This might have given visual as well as textual inspiration to a crusading King as he read his psalter. Louis went on Crusade more than once, seeking to free a Jerusalem which (like Lot, perhaps) he saw as captive and in need of rescue from a heathen enemy. The Abram in this illumination would have been a powerful and encouraging exemplar for the French king.

References

Hanna, Ralph. 1977. ‘The Sources and the Art of Prudentius' Psychomachia’, Classical Philology, 72: 108–115

Phillips, Jonathan P. 2007. The Second Crusade: Extending the Frontiers of Christendom (New Haven and London: Yale University Press)

Saint Ambrose of Milan. 2000. On Abraham (Etna, California: Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies)

Smith, Macklin. 1976. Prudentius’ Psychomachia: a Reexamination (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Commentaries by Michele Luigi Vescovi