Song of Solomon 4:1–7

All’s Fair In Love

Piero della Francesca

Madonna del Parto, c.1455–59, Fresco, transferred onto wood, 260 x 203 cm, Monterchi (Arezzo), Cappella del Cimitero; akg-images / De Agostini Picture Lib. / G. Dagli Orti

A Monumental Maiden

Commentary by Mary Kisler

Painted for the tiny Chiesa di Santa Maria in Momentana, beside the cemetery in Monterchi, Umbria, Piero della Francesca’s Madonna del Parto is revealed to us by two angels, one a mirror of the other. Between them, they hold open the draped entrance to the padiglione or tent that both shelters and reveals the figure of the Virgin.

Magnificent in scale, Mary points to the unlaced opening in her gown, (a traditional maternity gown of fifteenth-century Tuscany), indicating the birth that will take place, and that will lead to spiritual salvation. Like the padiglione’s lining of white ermine, Mary’s shift or undergarment symbolizes the purity of her womb, the preservation of her immaculate state (Apa 1982: 154).

Mary’s stomach, projecting forward, is positioned at the height at which a priest saying Mass would elevate the host (or consecrated bread), reinforcing a connection between the two. The source of the world’s salvation is nurtured in the body of a woman. And at a certain time of the year, light sends its rays through the tiny window above the entrance on the opposite wall to rest on the belly of the Virgin. The infant Christ nestling inside the vessel of his mother’s womb foreshadows his crucifixion and entombment, his sacrifice to save the world (Apa 1982: 156).

Piero draws on his knowledge of mathematical harmony and balance to reveal a mystery, for the Virgin’s halo reflects not her head and shoulders, but the tiled floor beneath, a detail that only became obvious after restoration in the 1990s. Drawing on the belief that light can pass through crystal without shattering it, it becomes a symbol used to depict both the Annunciation to Mary, and her own Immaculate Conception within the body of her mother Anna, who was past the age of childbearing.

Mary’s purity is symbolized by her own transparency. The fact that Mary’s halo reflects the pattern of floor tiles beneath her suggests that her body is no obstruction to the passage of light; just as Christ the Light can enter her womb while leaving her virginity intact.

While Carlo Crivelli’s painting (elsewhere in this exhibition) is laden with symbols, Piero has distilled the Song of Solomon’s paean to purity—‘You are all fair, my love; there is no flaw in you’—into a majestic image suffused with mathematical harmony and innate power.

References

Battisti, Eugenio. 1971. Piero della Francesca, vols 1 & 2 (Milan: Istituto Editoriale Italiano)

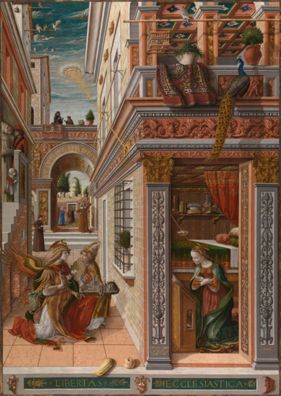

Carlo Crivelli

The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius, 1486, Egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm, The National Gallery, London; NG739, ©️ National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

A Feast for the Eyes

Commentary by Mary Kisler

Carlo Crivelli’s The Annunciation, with St Emidius is like a medieval tapestry, rich with colour and movement; laden with both symbolism and historical specificity. Commissioned for the Church of Santissima Annunziata in Ascoli Piceno, it celebrates the partial grant of self-government to the city by Pope Sixtus IV in 1486. The news arrived on 25 March, the feast of the Annunciation, a theme which Crivelli adapts so as also to honour the town’s patron saint, Emidius.

At the left of the scene, members of the Observant Friars, commissioners of the painting, are informed of the grant. But only the small child witnesses the angel Gabriel, white lily of the Annunciation in hand, whose progress has been halted by St Emidius, holding a model of Ascoli. The angel’s fantastical costume has still not settled after his descent, but neither seems aware of the rush of air that, having whipped the trees in the enclosed garden at the rear of the composition, has passed overhead. The Dove of the Holy Spirit flies onward, carrying word to the Virgin.

On one level, the painting is a paean to the bodily senses—sound, smell, touch, and taste—but each of these is also the bearer of spiritual meaning. Mary is kneeling at her prayer stool in the doorway, its scarlet and gold curtain drawn back to reveal a richly decorated patrician interior rather than a humble abode. On a high shelf, precious containers symbolize aspects of Christian teaching: books (the Word); a gold candlestick; and an alabastron or ointment jar. Gold, the most precious metal on earth, reflector of light and therefore knowledge, was gifted to the infant Christ by the wise men, along with frankincense and myrrh.

The dizzying array of objects constantly draw the eye backwards and forwards in Crivelli’s painting, but there is one item, balanced almost casually, that may relate to the lyrical final line on the Song of Solomon. On the shelf above Mary, a translucent glass vessel stands, the light passing through it illuminating the grain of wood covering the wall. It represents the purity of the Virgin Mary, before, during, and after birth, for ‘You are all fair, my love; there is no flaw in you’ (Song 4:7).

Gretchen Albrecht

Pacific Annunciation, 1983, Acrylic on canvas, 153 x 306 cm, Collection of the artist?; ©️ Gretchen Albrecht

The Space Between

Commentary by Mary Kisler

In the abstract paintings of Gretchen Albrecht, the hemisphere found so often in Romanesque and Renaissance art and architecture becomes both form and frame, while the gesture, movement, and meaning of narrative painting is translated into the fluidity of paint itself.

Speaking of her own first visit to Italy in 1979, Albrecht recalls:

a revelation of the power of painting hit me when I looked at these historical works. The ability of paintings to emotionally affect and carry meaning is as relevant today as it was then … aspects of the everyday found in many Renaissance paintings—things we all recognize and can share—can also be imbued with a sense of mystery and significance. (Albrecht, email to Mary Kisler, 19 July 2001)

In Pacific Annunciation, the literal interpretation of the Annunciation in Medieval and Renaissance painting has been abstracted, refined, and taken to its very essence. The Angel Gabriel descends to tell Mary that she has been chosen above all women to bear the Son of God. He alights before Mary, sweeping iridescent arcs of delicate pink suggesting the shimmering of folding wings, counterbalanced by the deep, contemplative blue of the Virgin’s cloak.

Albrecht’s canvases are sites of containment where meaning is explored, revealing truths that are both specific and universal. One is reminded of the first line in chapter 4 of the Song of Solomon: ‘Behold, you are beautiful, my love, behold, you are beautiful! Your eyes are doves behind your veil’.

This sense of something subtly veiled, yet also revealed, is inherent in Albrecht’s Pacific Annunciation. The delicate pinks of sunset, the sun’s globe shimmering on the horizon before sinking into darkness, the folding of light against the pale night sky above the Pacific Ocean...

Sometimes referred to as Stella Maris, Star of the Sea, the Virgin Mary’s association with the oceans is traditionally symbolized by a star on her deep blue cloak, referring to the Jewish form of her name of Miriam (‘sea of bitterness’). Yet scoop water from the ocean, and deepest blue becomes translucent, full of light. Suggesting sky and water, light and profound depth, Pacific Annunciation is immersive, sentient, gently revealing its meaning beneath a veil of colour and movement.

References

Smythe, Luke. 2019. Gretchen Albrecht: Between gesture and geometry (Auckland: Massey University Press)

Piero della Francesca :

Madonna del Parto, c.1455–59 , Fresco, transferred onto wood

Carlo Crivelli :

The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius, 1486 , Egg and oil on canvas

Gretchen Albrecht :

Pacific Annunciation, 1983 , Acrylic on canvas

A Song, a Canticle, a Prayer

Comparative commentary by Mary Kisler

The poetic beauty of the Song of Songs has resonated through the centuries and in different forms of faith—Jewish, Christian, Muslim—while influencing many forms of the arts, each period interpreting the rich imagery of the text in different ways. A traditional prayer, often sung, drawn partly from the Song of Songs and also from the Book of Judith, contains the lines: Tota pulchra es, Maria. Et macula originalis non est in Te, ‘You are all beautiful, Mary, and the original stain [of sin] is not in you’. The Song lends itself to many interpretations, but none can dispute its lyricism, its rich metaphors of containment, its meaning resolutely uncontained.

The Beloved’s purity in the Song becomes specifically attached to the Virgin Mary at the Annunciation and after birth, a purity often symbolized in religious art as a clear vessel that contains liquid through which light may pass. Yet for many readers, the Song’s lyricism pertains equally to earthly love and desire. In just seven verselets in Song 4:1–7, we are invited to imagine the deep evening shadows of the Galaad hills, the soft white of freshly washed sheep, the blush of pomegranate seeds, tall towers, fawns amongst lilies, the heady perfume of myrrh. All these are symbols of faith, but equally a paean to the senses. Visual artists who interpret these texts can, in turn, invite their viewers to wander in both sensory and metaphorical landscapes.

Carlo Crivelli’s Annunciation is rich with symbols: the freedom of the doves above the convent to fly unchecked, and to return to the dovecote at will, as opposed to the caged goldfinch, the red dash on its head believed to have occurred when it plucked a thorn from Christ’s brow before the crucifixion. The peacock symbolizes immortality represented in the resurrection in Christianity, but is also the attribute of Juno, Roman goddess of childbirth. Like the Song of Songs, Crivelli’s painting, if we will but ‘listen’, is rich with sound—the rush of wind, the rustle of trees, the murmur of voices, the chirping of birds.

Anatolian carpets refer to Italian trade with the East, their abstract patterns a reminder that not all faiths rely on figuration to represent meaning. Even the enclosed garden (its upper wall freshly mended), is echoed in the tied paper that functions as a stopper for the phial of water on the Virgin’s shelf, both symbolizing her closed perfection even after birth. And for everyday women in the Renaissance, the Virgin’s library suggests that knowledge is the key to understanding, rather than just the right of men.

Containment and liberation are also central to Piero della Francesca’s Madonna del Parto. The womb of the Virgin serves as a ‘mantle’ of the unborn Christ, the source of the world’s salvation, just as the tent in which Mary stands protects her in turn. So too the Chapel at the edge of the graveyard in Monterchi in which the painting stands is the site at which the people worship, the altarpiece signifying the belief in the resurrection of the faithful after death. Chapel, altarpiece, padiglione, the Virgin herself all incorporate ‘body as well as spirit, power as well as vulnerability, death, as well as life and rebirth’ (Ford 2004: 93–113).

The Virgin was given further valence in the Western tradition when the fourteenth-century charismatic preacher San Bernardino of Siena introduced an apocryphal element to Christ’s conception by stressing that the angels in heaven held their breath while they waited in hope that Mary would accept the responsibility of the Annunciation (Origo 1963: 75). It was hers to decide. Such an interpretation allows women a place in spiritual discourse denied them in texts that define Mary solely as the passive vessel in which Christ was conceived.

The infinitesimal space at the centre of Gretchen Albrecht’s Pacific Annunciation, where the two quadrants meet, is fraught with this moment—a pause, an expectation, a desire, an acceptance—when the movement held within the tracing and re-tracing of the artist’s hand as it arcs over the canvas reflects the oscillation of invitation, consideration, acquiescence between the messenger of God and the woman who will provide Christ with his humanity. We feel this movement; this distillation of narrative, so full of possibility. The poetic narrative or Word familiar in biblical text is translated into the gestural movement of paint across canvas, both specific and open to meaning, like the lyrical poetry of the Song of Solomon itself. Each ‘figure’ contained in its quadrant—balanced, equal—suggests a perfect harmony in which ‘there is no flaw’ (Song 4:7).

And as the title Pacific Annunciation suggests, further miracles can be looked for in the light of this one—in new and different spaces and new and different times.

References

Apa, Mariano. 1982. ‘La resurrezione, il parto e il sepolcro nell'opera di Piero della Francesca tra San Sepolcro e Monterchi’, Convegno internazionale sull'arte di Piero della Francesca, 1980 (Biblioteca comunale di Monterchi)

Ford, K. C. 2004. Portrait of Our Lady: Mary, Piero, and the Great Mother Archetype. Journal of Religion and Health, 43.2: 93–113

Herbermann, Charles G. (ed.) 1917. The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 1: Aachen–Assize (New York: Robert Appleton Company)

Origo, Iris. 1963. The Merchant of Prato (London: Penguin)

Commentaries by Mary Kisler