Song of Solomon 8

Bewildering Beauty and Lavish Love

Georgia O'Keeffe

Waterfall—No. III—'Iao Valley, 1939, Oil on canvas, 61.6 x 50.8 cm, Honolulu Museum of Art; Gift of Susan Crawford Tracy, 1996, 8562.1, ©️ 2022 Georgia O'Keeffe Museum/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo: Art Resource, NY

The Eye of the Beholder

Commentary by E.S. Kempson

In 1939, Georgia O’Keeffe drove a borrowed station wagon through the rambling jungles of Maui. As long as she returned with two paintings that her funders—the Hawaiian Pineapple Company—could use in advertisements, she was free to travel and paint as she pleased.

Waterfall, No. 3, ‘Īao Valley, Maui (1939) is one celebrated result. Its arrangement creates a dynamic ‘spatial vortex, a compositional device’ which O’Keeffe explored at length in later works (Groarke & Papnikolas 2018: 116–17). Smoothing and foreshortening the steep valley walls creates an immediacy; the dividing river below and ribbon of waterfall above appear equally close.

This vast landscape compressed into closeness creates the opposite effect to O’Keeffe’s famous paintings of flowers, enlarged into monumental grandeur. Nevertheless, both effectively transpose their subjects to a human scale. Like her potent floral images, Waterfall No. 3 bears a resemblance to a human body—one that harmonizes with Song of Songs’ likening of the beloved to a vineyard and garden (8:12–13).

O’Keeffe’s minimized depth of field and Y-shaped composition enable the lush valley walls to evoke thick thighs and the promise of fertility. The crux of the waterfall’s cleft may recall a woman’s most sexually intimate parts. The swirl of mist could echo the wisp of cloth painted on innumerable female nudes: a concession to modesty and nod to erotic mystery.

O’Keeffe, however, ‘always flatly denied’ that she meant to give her botanical images sexual overtones (Messinger 1989: 74). Do her stated intentions disqualify any bodily reading of her paintings? Similarly—despite the Song’s dearth of references to God—Jews and Christians traditionally read the poem allegorically, as depicting the love-dynamic between God and God’s people (be that Israel or the Church). Later receptions of both O’Keeffe and Song of Songs suggest that art can reveal realities that the creator may not have intended.

References

Groarke, Joanna L., and Theresa Papanikolas (eds.). 2018. Georgia O’Keeffe: Visions of Hawai’i (Munich: The New York Botanical Garden and DelMonico Gooks, Prestel)

Messinger, Lisa Mintz. 1989. Georgia O’Keeffe (London: Thames and Hudson and The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Unknown Flemish or German artist

An opening from the Song of Songs, from the Rothschild Canticles, Late 13th/early 14th century, Illuminated manuscript, 118 x 84 mm, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University; Beinecke MS 404, ff. 65v-66r., Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Heavenly Love

Commentary by E.S. Kempson

In the late twentieth century, a young scholar leafing through the thirteenth–fourteenth-century Rothschild Canticles experienced ‘awe and astonishment … bafflement and surprise’: ‘the manuscript represented a veritable explosion of visual and iconographic inventiveness that transcended the norms of … medieval art’ (Hamburger 2014: 125).

The illuminated manuscript bursts with clusters of biblical, liturgical, and theological phrases. It is an example of what is called a florilegium. The reader is supposed to dwell on, repeat, and elaborate on these texts in prayer. The page shown here includes a passage from St Augustine (354–430 CE) beginning ‘Inuoco te deus …’: ‘I call you, my God, into my soul, that prepares to seize you out of the desire you have inspired within it’. Song of Songs 8:14 is quoted: ‘Fuge, dilecte mi’ meaning ‘Fly my love’.

On the left-hand folio shown here, a figure points right, directing the reader’s attention to a woman, represented in the facing folio, who lies in bed, not asleep but gazing heavenward at the noonday sun. Its wavy-radiance pulses like the glory of God among crests of clouds, a scattering of stars, and the crescent moon. The figure of Christ emerges from the clouds and reaches downwards, mirroring the woman’s up-stretched arms. The intimacy between the woman and Christ intensifies in subsequent pictures, as the sun descends to caress her face and finally the woman and Christ embrace. Like many mystical medieval texts, the Rothschild Canticles used the Song of Songs as allegorical language for the love between Christ and one’s soul. It was less common to visualize such love so explicitly.

The following folios provide trinitarian images for contemplation. They portray ‘such unlikely statements as “Truly you are a hidden God” and “My center is everywhere, my circumference nowhere”’ in pictorial form (Newman 2013: 133). The Rothschild Canticles’s visual ‘apophatic literalism’ is practically unique, in that common verbal phrases that gesture towards ineffable aspects of divine reality are given literal visual depiction.

Over 600 years ago, somewhere in North-West Europe, a pious woman held this bespoke, costly, pocket-sized book. It is likely her responses ranged from prayerful meditation to mystic contemplation, and even to ecstatic visions.

Today, beholding these images on a glowing screen, we glimpse a world long gone. If we imaginatively enter that world, contemplating its text and images, we may find ourselves drawn yet further, towards its vision of divine love.

References

Hamburger, Jeffrey F. 2014. ‘Encounter: The Rothschild Canticles’, Gesta: International Center of Medieval Art, 53.2: 125–27

______.1990. The Rothschild Canticles: Art and Mysticism in Flanders and the Rhineland circa. 1300 (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Newman, Barbara. 2013. ‘Contemplating the Trinity: Text, Image, and the Origins of the Rothschild Canticles’, Gesta: International Center of Medieval Art, 52.2: 133–59

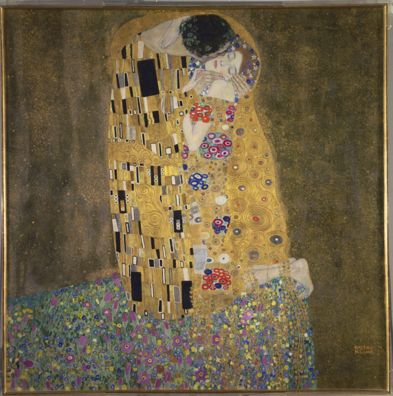

Gustav Klimt

The Kiss (Lovers), 1908, Gold leaf and oil on canvas, 180 × 180 cm, The Belvedere, Vienna; Acquired from the artist at the Kunstschau, Vienna, 912, Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Profound Familiarity

Commentary by E.S. Kempson

Gustav Klimt’s painting The Kiss (1907–08) is exceptionally popular—perhaps because innumerable viewers find its depiction of love enthralling. Its appeal across cultures and eras may be partly attributed to Klimt omitting most specifics of location, time-period, and the lovers’ identities. By melding the lovers’ bodily forms and simplifying their clothing and surroundings into flat geometric designs, Klimt shifts the focus towards the feeling or essence of their amorous union, rather than questions of ‘who?’, ‘when?’, or ‘where?’.

Ignorance among many viewers of the painting’s historical context contributes to its iconic quality. For instance, if one doesn’t know that unstructured clothes with flowing patterns were fashionable in Klimt’s social circle (Whitford 1993: 96–97), then the clothing style may amplify an impression of timeless abstracted ornamentality. The resulting image evokes (romantic) love itself, transcending its manifestation in two individuals.

Similarly, the Song of Songs is spare on identifying details. Its vagueness around location, timeline, and identities focuses the reader’s attention on the lovers’ love-dynamic, one that may be shared by innumerable other couples.

Klimt’s innovative use of gold leaf heightens the effect of transcendence and timelessness (Fliedl 1997: 115). Gold’s warm perpetually untarnished brilliance recalls life-giving light; its costliness may remind one of Song of Songs 8:7, that love is beyond price; encircling the couple is a swirling golden nimbus that resembles a halo. Indeed, ancient Christian mosaics in Ravenna and the icons of St Mark’s in Venice inspired Klimt to create comparable effects (Whitford 1993: 86). In The Kiss, love appears all-engulfing, eternal, and radiant.

But this transcendent love is nonetheless decidedly physical and embodied. In contrast with the shimmering geometric forms, there also emerge more naturalistically rendered limbs: curling toes, grasping hands, kissing cheeks, and a blissful face. The Song is likewise rich in bodily references.

The Kiss’s fame, ironically, also undermines its power. Over-familiarity can reduce its profundity to cliché. Once mediocre reproductions rob the painting of its scale, golden glow, and surprising technique, The Kiss risks being reduced to sentimentality. The same can be said of iconic passages in Song of Songs, such as 8:6–7, when they are oft-repeated and up-rooted from their context. When the Song is mostly heard in small excerpts, such as in weddings, much of the poem’s power is lost. What is otherwise a captivating torrent of passion and imagery can diminish to a brief burst of tired familiar phrases.

References

Fliedl, Gottfried. 1997. Gustav Klimt, 1862–1918: The World in Female Form (Köln: Taschen)

Whitford, Frank. 1993. Gustav Klimt, Artists in Context (London: Collins & Brown)

Georgia O'Keeffe :

Waterfall—No. III—'Iao Valley, 1939 , Oil on canvas

Unknown Flemish or German artist :

An opening from the Song of Songs, from the Rothschild Canticles, Late 13th/early 14th century , Illuminated manuscript

Gustav Klimt :

The Kiss (Lovers), 1908 , Gold leaf and oil on canvas

Endless Love

Comparative commentary by E.S. Kempson

For many, reading the Song of Songs is both a beautiful and bewildering experience. With no linear progression or discernible plot, one couldn’t call it a love story.

The Song’s swirl of vignettes, love-confessions, and imaginative speeches have a similar effect to the near-abstracted stylized lovers in Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss. The lack of any traceable narrative or details of the lovers’ identities means that instead of portraying the lovers’ characters, the works portray the character of romantic love. As J. Cheryl Exum observes:

just as the harmony of the male and female voices presents, on the poetic plane, their sexual union, so the poetic rhythm of the Song, ever forward then returning, reflects the repetitive pattern of seeking and finding in which the lovers engage, which is the basic pattern of sexual love: longing—satisfaction—renewed longing—and so on. (Exum 2005, 11)

Exum has a gift for illuminating other opaque passages of the Song as well.

When the Song’s imagery is disorienting—many lovers today would never think to compare their beloved to a town or a vineyard—Georgia O’Keefe may help one see: the similarities of landscapes, lilies, and lovers can resonate now as they did millennia ago. If a Hawaiian valley or flower painted by O’Keefe can look erotic to the eye of the (modern) beholder, the Song’s imagery in 8:10 and 8:12 is not such a stretch.

In 8:6–7, however, the poem offers its climactic encapsulation of love—the poem’s heart—clearly and lucidly: ‘Set me as a seal upon your heart … for love is strong as death’ (NRSV). Just as The Kiss became iconic in part by being separated from its context, so too Song 8:6–7 has taken on an emblematic quality in Western culture. Once lifted from its literary and historical context, it can be treated as a timeless expression of transcendent truth: that true love can become central to a person’s very being, in a way that is priceless, indestructible, and everlasting.

The illuminations in the Rothschild Canticles include gold leaf—that expensive radiant metal that never tarnishes—to imply the eternal spiritual value of its lessons in drawing close to God in love. By gilding The Kiss with gold leaf, Klimt not only enhanced the painting’s material and artistic value, but also implied a spiritual profundity to the lovers’ embrace. Analogously, when the poetry of Song of Songs is read as Scripture, its value is transfigured. Canonizing the book as a holy text both grants it spiritual authority and also commends its passages as wise and worthy of pondering, particularly by anyone searching for sacred wisdom to answer life’s existential questions.

And yet, there is no reference to God in the Song, except perhaps 8:6. Some scholars see in that verse an oblique mention of God (‘flame of the LORD’), though others strongly dispute such claims (preferring ‘raging flames’) (Attridge et al. 2006: 911). But this is beside the point, because Jews and Christians have read the Song in a manner similar to that in which many people now view O’Keefe’s paintings: if a landscape can reveal something about womanly beauty, so too may love poetry reveal something about humanity’s search for God. As long as the analogy is in itself illuminating, the poet or artist need not have intended it; those who have eyes that see it or ears that hear may still possess the insight. Ancient Israelites, medieval mystics, and modern scholars have all in turn been mesmerized by a fluctuating sense of bereft distance from God and consoling, bliss-filled closeness to the divine, as found in the Rothschild Canticles.

Though Chapter 8 is the Song’s last chapter, its final verses do not conclude the book so much as start the poem over again.

The man’s request to hear his lover’s voice (v.13) and her reply in which she sends him away and allusively calls him to her at the same time (v.14), take us back to the beginning. Only when the woman seems to send her lover away can the poem begin again with longing and the quest to gratify desire. (Exum 2005: 245)

That the Song has no end underlines its conviction that true love cannot be ended, not even by the finality of death.

References

Attridge, Harold W., Wayne A. Meeks, and Jouette M. Bassler (eds.). 2006. The HarperCollins Study Bible: New Revised Standard Version, Including the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books (San Francisco, Calif: HarperSanFrancisco)

Exum, J. Cheryl. 2005. Song of Songs: A Commentary (Louisville: Presbyterian Publishing)

Commentaries by E.S. Kempson