John 17

A Consecration Prayer

Hans Namuth

'Jackson Pollock in 1950', 1950, Gelatin-silver print, 20.3 x 20.3 cm, Associated with 'Jackson Pollock', 19 Dec 1956–3 Feb 1957, The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona © 1991 Hans Namuth Estate

Perfectly One

Commentary by Charles Pickstone

The mature works of the American Abstract Expressionist painter, Jackson Pollock (1912–56), were produced by laying a canvas on the studio floor and then dripping, pouring, or brushing paint across its surface. This photograph captures Pollock flicking paint across the canvas ‘like the follow-through a fly fisherman performs when punching a line out into the wind’ (Searle 1999). The consequent filigree of lines has, at best, a quite unexpected, delicate beauty and sophistication.

By placing his canvas on the floor, Pollock can put his whole body into making his art. He is so caught up in the act of creation—the painting is as much a trace of action as a static final object—that any divide between artist and artwork, person and object, disappears. The artist enters into his creation so completely that the work is Pollock himself, the fine skein of its surface his psyche. In its public exposure of a raw and intimate self that most people would conceal, it feels almost blasphemous.

In John 17, Jesus talks about the unique and extraordinary unity that exists between himself and the Father. Jesus has been able to reveal God’s name (his identity) (v.5) to human beings because ‘all mine are thine and thine are mine’ (v.10). He prays that his disciples may be one just as ‘thou, Father, art in me, and I in thee’ (v.21).

In Hans Namuth’s photo, the palpable unity of artist and artwork, and the consequent enfleshment in paint of the artist’s inmost self, is beautifully manifest. It can open a window onto the way the unseeable God (Colossians 1:15) is revealed in the flesh of his Son. Meanwhile the alluring yet vulnerable beauty of the artwork is perhaps analogous to the vulnerable yet appealing figure of Jesus at the Last Supper, on the night of his betrayal—the night before he revealed his glory on the cross. He is the intimate revelation of the Father.

References

Searle, Adrian.1999. ‘Splash bang dollop, 9 March 1999’, www.theguardian.com [accessed 1 November 2018]

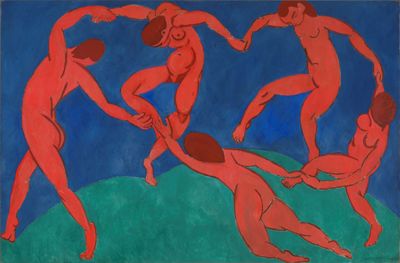

Henri Matisse

Dance (Dance II), 1909–10, Oil on canvas, 260 x 391 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg; Entered the Hermitage in 1948, originally in the Sergei Shchukin collection, ГЭ-9673, Photo courtesy of the State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Joy Fulfilled

Commentary by Charles Pickstone

The French painter Henri Matisse (1869–1954) is often called a Painter of Paradise. The Dance (La Danse) is a paradisal scene of Eden restored in which four women and a man (freed of accoutrements in this return to innocence) perform a round dance with immense energy and vigour.

The energy of the dance is infectious. The circle is almost but not yet complete—two of the dancers are striving to link up—and the spectator is inevitably caught up in the dynamic of the lower figure’s leap as she tries to grasp the hand of the figure on her left. Each figure looks down and inwards in a self-contained way, but each is also caught up in the joyous and liberating enterprise of the dance. They offer themselves totally—mind, body and spirit—to the common purpose. The break in the circle may also be read as an invitation to the spectator—the figures are not excluding of any outsider.

In John 17:19 Jesus prays for the disciples: ‘I consecrate myself, that they also may be consecrated in truth’. The purpose of Jesus’s ministry was not to establish an exclusive club but to communicate his identity with God the Father as widely as possible, to invite the whole world to consecrate itself single-mindedly to the truth of his identity, and thus to join in the perichoresis, the dynamic of mutual love, of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The German theologian Jürgen Moltmann (b.1926) reads an ancient Easter homily as evoking the image of the risen Christ as the ‘leader of the mystic round-dance’ (Moltmann 1985: 307), with the church as the bride who dances with him.

This is a glorious scene, reminding us that glory is infectious: ‘The glory which thou hast given me I have given to them, that they may be one even as we are one’ (v.22). In this image of diversity caught up in the unity of a common purpose we perhaps discover our own somatic response to God’s glory as we too are invited to shed our accoutrements, to consecrate ourselves to the truth, and to join in the dynamic and lyrical unity of Father and Son and Holy Spirit.

References

Moltmann, Jürgen. 1985. God in Creation: An Ecological Doctrine of Creation, trans. by M. Kohl (London: SCM), citing Pseudo-Hippolytus. Cf. Giuseppe Visonà. 1988. In sanctum Pascha (Milan: Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore), pp. 315–16

Sean Scully

Wall of Light Sky, 2000, Oil on linen, 243.8 x 365.8 cm, Dublin City Gallery; Presented by Patrick and Margaret McKillen, 2005, Reg. 1992, © Sean Scully

A Fragile Harmony

Commentary by Charles Pickstone

Visually, the three-panelled triptych format—especially popular for altarpieces from the Middle Ages onwards—offers a stabilizing cohesiveness. The Irish artist Sean Scully turned to this comforting framework to structure a series of works that he undertook in the wake of a difficult bereavement (his son Paul died in 1983).

Wall of Light Sky was acquired by the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin in 2006. Three conjoined vertical canvases each contain three rectangles, comprising two, three, or four stripes loosely painted with a vulnerable ‘skin’ of paint. The rectangle format focuses and contains their complexity. The central panel is the most complex with its total of eleven differently-aligned stripes, but the simpler flanking ‘wings’ have an equal charge. The loosely painted texture (or ‘painterly’ quality) of the coloured stripes, with their imprecise edges, gives them an endearing frailty—perhaps one can sense the vulnerability of the artist behind this apparently large and stable artwork.

In John 17, sometimes known as the ‘Consecration Prayer’, Jesus repeatedly prays that his disciples may be one as he is one with the Father (vv.11, 21, 22, 23) through their being ‘consecrated in the truth’ (v.19). Earlier, in chapter 16 verse 13, it is the Holy Spirit—the Spirit of truth—who, Jesus promises, will lead the disciples to the complete truth into which Jesus prays they may be consecrated, and who will glorify Jesus. John 17 is therefore a remarkable meditation upon the Trinity: Jesus—the perfect revelation of the Father (v.6)—prays that his disciples may be united in their consecration in the Father’s truth revealed by the Spirit. In this unity they in turn will become living signs of the Trinity.

The panels of Scully’s triptych are almost flesh-like, partly on account of the tone of their colours, but mainly in the texture of their painted surface, which suggests vulnerability. In their fragile harmony they present an icon of the unity for which Jesus prayed on behalf of sinful yet redeemed Christian believers, praying that despite their brokenness and rough edges, believers might model the powerfully dynamic and yet stable unity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Hans Namuth :

'Jackson Pollock in 1950', 1950 , Gelatin-silver print

Henri Matisse :

Dance (Dance II), 1909–10 , Oil on canvas

Sean Scully :

Wall of Light Sky, 2000 , Oil on linen

Dancing to Glory

Comparative commentary by Charles Pickstone

This remarkable chapter, Jesus’s final message to his disciples as a group, gathered together for the Last Supper, is the culmination of John’s record of Jesus’s gradual revealing of his identity as it develops through his Gospel. The Gospel’s magisterial first chapter begins with its climactic ‘the Word became flesh and dwelt among us … we have beheld his glory’ (John 1:14), and is succeeded, episode by episode, by the long sequence of signs, deeds, and teachings through which Jesus gradually reveals his true glory to the disciples. Slowly they, the disciples, and we the reader, realize that this human, embodied person, Jesus, is the Son of God the Father.

And now, in John 17, the evening before his passion and death, Jesus extrapolates forward to the ultimate revelation of his glory that will become evident in his cross and resurrection, and he prays that all those who have grasped (or perhaps, better, been grasped by) his kinship with the Father may have the same relationship with each other as he has with the Father, a relationship of mutual love. Thus at the culmination of the Fourth Gospel, John reveals not only how the glory of God is mediated through the flesh of the Son, but also calls for the disciples (and thus all Christians) to manifest the same relationship of love for each other as Jesus has with the Father.

And even when Jesus has returned to the Father, there will not be an absence between him and the disciples, for the Holy Spirit, the Paraclete, who has been celebrated in the previous chapter (John 16:7; cf. John 14:16), will be with them, reminding them of Jesus’s presence, encouraging them to glorify the Father through the Son in worship (doxology—literally ‘giving glory’).

For Christians today, how is this relationship between Jesus and the Father as expressed by the Spirit best communicated? Given the emphasis in the Fourth Gospel on seeing (as opposed to blindness), and on glory, which is often expressed using visual imagery, the visual arts are potentially a valuable and valid means of communicating the glory of God.

For example, in the work of Jackson Pollock, we see a profound analogy for the relationship between Father and Son in an artist so totally identified with his artwork that the artwork is the artist; the artist’s vulnerable inner self, scarred yet beautiful, is awesomely manifest in the artwork. This is, perhaps, mainly because his ‘paintings’ are as much action as they are object. An object is inevitably distinct from its creator, whereas an action implicates the enfleshed being of the person who performs it. Jesus’s life perfectly expresses the glory of the Father.

Henri Matisse’s Dance takes up this sense of movement necessary to any potentially great work of religious art. His dancers invite us (like John Bunyan’s pilgrim) to shed the burden of sin and shame, to enter the paradise of open-hearted relationship characteristic of the profound unity for which Jesus prayed on behalf of all who behold his glory, and to dance out in joyful, generous, and carefree expression their mutual love. They invite us to join the round-dance of the redeemed to which all are invited by the Spirit.

Sean Scully’s triptych is also a dance, albeit in a different mode. The complex inter-relationship of the three differentiated panels creates a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. The dance of the complex elements of the triptych presents a unity in diversity—just as Jesus prayed that the always-fissiparous fellowship of diverse believers that is the church might be united in worship of the glory of God revealed in the flesh of his Son to which they are invited by the call of the Spirit.

Scully’s triptych is a modern day analogue of Andrey Rublyov’s great icon of the hospitality of Abraham (Genesis 18). An icon is not only an object but also a gaze—an icon initiates a relationship with the viewer. A triptych inevitably presents a subtle hierarchy (the central panel is unconsciously read as prominent) but a good artist can use this to create a dynamic relationship between the three panels, so that the eye constantly moves across the work, following the ‘dance’ of the panels. Scully’s work here invitingly mirrors the complex prayer of those who together have glimpsed Jesus’s enfleshed presence as the final revelation of the divine glory of the Father and who respond to the invitation of the Spirit, caught up in ever-changing contemplation of the mystery of God, and the desire to express that mystery in worship and in mutual love.

Commentaries by Charles Pickstone