Colossians 1:1–20

The Cosmic Christ and His Gospel

Unknown artist

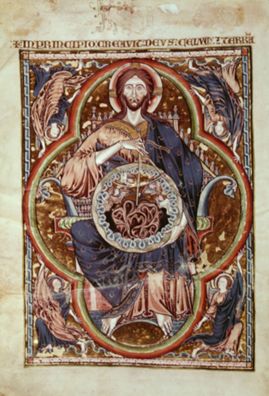

Christ Pantocrator, from The Bible of St Louis (Rich Bible of Toledo; Bible of Toledo), 1226–34, Illuminated manuscript, 422 x 300 mm, Toledo Cathedral; Vol.1, fol. 1v, Album / Alamy Stock Photo

Pantocrator Mother of Creation

Commentary by Harry O. Maier

The Toledo Bible was created for the religious instruction of Louis IX of France. Such Bibles, known as Bibles Moralisées, used pictures accompanied by short descriptions to draw theological/allegorical and moral meanings from select Old and New Testament passages/events.

Theological/allegorical meanings suffuse the work: God the Son, Pantocrator, is the ruler and creator of the universe, but he is crowned by a cruciform nimbus; his blue cloak over his brown tunic symbolizes the Word becoming flesh; his throne and feet on a gold sphere indicate his divinity; the background gold leaf represents the heavens; the angelic figures at each corner, the heavenly host. He is enthroned in the act of creation; his left hand supporting the universe and the compass in his right inscribing the unformed, chaotic deep of Genesis 1:1 (below) with order.

The illumination also captures ancient and medieval teachings about God Pantocrator as both Son and nurturing, birthing Mother. English anchorite and mystic Julian of Norwich (c.1342–c.1430) presents a vivid expression of this tradition: ‘[O]ur Saviour is our very mother in whom we be endlessly born, and never shall come out of him’ (Revelations of Divine Love 14.52).

The Toledo Bible image is similarly lively and dramatic. The orb held between the Son’s spread legs depicts the separated waters under the dome of Genesis 1:6–7. But as its position suggests, it is also a womb. This illumination offers a provocative aid for visualizing Colossians 1:16, that, ‘in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him’. Creation literally passes ‘through him’.

Both Colossians and the Pantocrator of the Toledo Bible express a God simultaneously transcendent and immanent; enthroned in heaven (Colossians 3:1) and incarnate (1:15, 19); a God in and for whom all creation exists; God the Son, ever present and always inscribing and birthing the always new and vital universe after his own youthful image.

In his hands, on, from, and through his lap, ‘all things hold together’ (1:17) and find their origin and destination in ‘the first born of all creation’ (1:15).

References

Julian of Norwich. 1999. Revelations of Divine Love (New York: Penguin Classics)

Unknown artist

Cameo: Gemma Augustea (fragment), 9–12 CE, Onyx, two layers, 19 x 23 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; IXa 79, Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Whose Gospel?

Commentary by Harry O. Maier

The letter to the Colossians is a polemical writing addressed to Christians at Colossae, Laodicea, and Hierapolis in central Asia Minor (modern-day Türkiye), who are following what Paul calls ‘philosophy and empty deceit’ (2:8). But Paul quickly shifts his focus from his audience to the grace of God and the gospel that is the source of any commendation he can offer.

The Gemma Augustea proclaims another gospel spreading throughout the world. Indeed Paul’s word ‘gospel (euangellion)’ is an imperial term that was used to describe the ‘good news’ of the coming of Augustus Caesar and the peace he brought to his empire. This luxury object offers a snapshot of the ‘fruits’ of Augustus’s reign.

It is divided into two registers. Above, Augustus, in the guise of the top Roman god, Jupiter, is seated alongside his wife Livia represented as the goddess Roma. Below are the fruits of this rule: Roman auxiliaries with helmets representing different corners of the Empire pull up a Roman trophy displaying despoiled enemy arms.

Two gospels: one of Jesus and the other of Augustus, both spreading through the world; there could not be a sharper contrast between them. One is centred in conquest and violence; the other is rooted in the grace and peace from God our Father (1:2), a grace and peace that Paul will go on to describe as won and proclaimed in the one vanquished and brutalized by Rome, Jesus Christ (v.20).

In the Gemma Augustea there is a transfer—riffing verse 13—‘into the kingdom of his [Jupiter’s] beloved son [Augustus]’, as attested by the brutal absorption into the empire through military victory. In Colossians the transfer is through ‘redemption, the forgiveness of sins’ (v.14), through Jesus’s paradoxical victorious defeat on the cross (v.15).

For Paul’s listeners there could not have been a more striking contrast in ‘gospels’ and as the letter proceeds from affirmation to censure, they will need to choose what version of good news they will cling to and follow: the one that exercises dominion by way of slavery or the one rooted in the grace and peace that bears the fruit of ‘love in the Spirit’ (v.8).

Unknown German artist

Peace movement in East Germany Poster 'Swords into Plowshares' with a note to a peace prayer at St Nikolai Church, Leipzig, 1988/89, Paint on paper, Location currently unknown; ullstein picture - Harald Lang

Shaking the Principalities and Powers

Commentary by Harry O. Maier

The Berlin Wall came down on 9 November 1989 without a single gunshot, largely thanks to the Church’s role in organizing non-violent resistance to the East German regime. Every Monday night, prayers for peace were conducted across East Germany. One month before the fall of the wall, in and around St Nicholas Church and other churches in Leipzig, more than 70,000 people gathered to pray for peace.

This poster announces these prayerful demonstrations. The logo of a blacksmith hammering a sword into a ploughshare, illustrating Micah 4:3, is modelled after Yevgeny Vuchetich’s statue donated to the United Nations by the Soviet Union in 1959. In 1980, graphic artist Herbert Sander adapted the image for the East German Protestant church, which created 100,000 copies for distribution through its congregations.

Through the eighties the image was widely reproduced on metal buttons, decals, posters, banners, and placards. When students started to wear it as a badge, the German regime prohibited its public display and expelled anyone who wore it to university, with the result that people began to appear in public with a hole cut out of the clothes where the logo had once been fastened.

Though Micah 4:3 sits alongside the image, an exegetical gloss might well be Colossians 1:19–20. Colossians celebrates peace and non-violent reconciliation in a provocative way. The words ‘to reconcile’ and ‘making peace’ are imperial terms celebrating the power of the emperor to pacify enemies through war. But in Colossians peace and reconciliation come through Jesus’s self-sacrifice. This is where the fullness of God is revealed, where swords are beaten into ploughshares, as the little one from Galilee dies in obedience to his own command to love one’s enemies and not to retaliate with violence.

In Leipzig, 70,000 little ones gathered to express Jesus’s way and, for a moment, the fullness of God was once again made flesh as the Son became incarnate amongst them. Such incarnation causes powers and principalities to quake as God moves the world towards justice and love. It happens in as small an act as praying with one another for reconciliation and peace, at 5pm every Monday.

Unknown artist :

Christ Pantocrator, from The Bible of St Louis (Rich Bible of Toledo; Bible of Toledo), 1226–34 , Illuminated manuscript

Unknown artist :

Cameo: Gemma Augustea (fragment), 9–12 CE , Onyx, two layers

Unknown German artist :

Peace movement in East Germany Poster 'Swords into Plowshares' with a note to a peace prayer at St Nikolai Church, Leipzig, 1988/89 , Paint on paper

The Dangerous Cosmic Christ

Comparative commentary by Harry O. Maier

The first twenty verses of Colossians are indomitably joyous, cosmically grand, and politically subversive. Paul rejoices in the reception of the gospel by a church he has never met (1:3–7).

Paul wants to root his audience in what they have known and what they have heard, in the hope that this joyous news will return them to their original faith. He inserts his listeners into a grand cosmic story.

Colossians 1:15–20, which some scholars believe is adapted after one of the earliest hymns of the Church, places Jesus’s believers within a narrative of sweeping proportion. Outside John’s prologue (1:1–18), it offers the highest affirmation of Jesus’s divinity in the New Testament and helped to form the Christian confession of the first four centuries of God as Trinity, as well as of Jesus as fully human and fully divine.

God the Father creates ‘all … things visible and invisible’, through and for the Son (1:16); the fullness of God dwelt in Jesus of Nazareth, visible image of the invisible God (1:15, 19). It is in the Church—amidst the believers Paul addresses—that this cosmic Christ is fully known and lived as his body (v.17). The fullness of his life courses through its veins.

This is an affirmation as politically subversive as it is dramatic. To make his points, Paul draws upon a register of imperial language: the terms ‘gospel’, ‘reconciliation’, and ‘making peace’ are words that everyday listeners to the letter would have immediately recognized as the ubiquitous imagery of the Roman Empire celebrating its emperor’s achievements.

Colossians 1:15–20 is cosmic in orientation but securely on the ground. How does God’s reconciliation work? By the shedding of blood. But not enemies’ blood as in the Empire. Rather, through the crucifixion of the one in whom the fullness of God dwells.

So it is that we come to our images, which help bring these truths to visual imagination.

Here the Gospel illumination, competing with the principalities and powers for allegiance, hovers over the Swords into Ploughshares logo of the East German Church. The GDR did everything it could to erase Christ’s body: it infiltrated it with Stasi agents; it restricted its members and destroyed its church buildings. The rainbow enclosing the central image, however, suggests God’s covenantal presence and God’s way with the world. The gospel grows and spreads, its tendrils reaching out, rooted in the hope for justice and humanity. Prayer at 5 pm on Mondays brings down the Berlin wall.

For those who belong to the body whose head is Christ (1:18, 24)—who live inside this cosmically grand vision—this may come as no surprise: we are the reconciled ones, who have found our peace in the one executed for love, and we are suffused with the presence of the ‘first born of creation’ (1:15), who, as the Christ Pantocrator of the Toledo Bible, also births creation. Here Christ is neither distant nor remote, ‘for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created’ (v.16). The Toledo Gospel implies an ever-birthing Son outside of whose womb we do not exist.

We do not live in a safe world, however. The Toledo Pantocrator’s cruciform nimbus reflects the strikingly subversive nature of Christian confession. As the East German Church logo suggests, hammering swords into ploughshares via prayer unfolds in contexts where the former far outnumber the latter. The fullness of God in the crucified one may be good news, but to the principalities and powers it is dangerous.

There they are in the lower half of the Gemma Augustea, wielding their reign of terror upon the earth. In the words of the roughly contemporary Roman historian Tacitus, ‘where they make a desert, they call it peace’ (Agricola 1.30). The wonder is that even these ‘thrones or dominions’ (v.16) are reconciled in Christ, who reconciles to himself ‘all things whether on earth or in heaven’ (v.20).

This happens ‘through the blood of the cross’, that is, not without the suffering that comes from love for enemies, as the entirety of Jesus’s life attests. The powers are there at every turn to ‘take us captive with philosophy and empty deceit’ (2:8), whether of a Roman imperial kind or of the more subtle versions of our modern contexts.

So it is that we remember the image of the invisible God, after whom we are made; we commit ourselves to the new birth the first born from the dead brings; and we seek to follow him in a life of prayer and costly discipleship.

Commentaries by Harry O. Maier