Exodus 11

The Death of the Firstborn

Works of art by Joseph Mallord William Turner, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Unknown artist

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema

The Death of the Pharaoh’s Firstborn Son, 1872, Oil on canvas, 7 x 124.5 cm, The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Gift of the heirs of L. Alma Tadema, SK-A-2664, Courtesy of Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

A Plague Upon Your House

Commentary by Itay Sapir

The Dutch-born, London-based orientalist painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema depicted the tenth plague of Egypt twice. A first treatment of the theme, The Sad Father, was created in 1859, but the canvas was later trimmed as apparently it didn’t satisfy the artist (Mason 2020: 220). The later version discussed here, painted one year after the première of Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Aida and thus in the midst of an Ancient Egypt craze, repeats the ‘Pietà’ formula and some Egyptian decorative elements present in the earlier painting, but otherwise proposes a wholly novel mode of storytelling.

Alma-Tadema frequently depicted Egyptian motifs and scenes, and his knowledge of that culture was vast, so that he could refer in his works to a ‘multitude of archaeological references’, many of which he encountered at the British Museum (Moser 2020: 197). Notable in this painting is the inclusion of a cartouche of Ramses II, connecting the scene to the specific Exodus episode it depicts, as that Pharaoh’s reign ‘was the period in which Moses … was placed by nineteenth-century scholars’ (Mason 2020: 221).

Beyond specific details, the painter seeks here to adopt the hieratic style of Egyptian art: the frontal, majestic, and massive central figures are passively, though nobly, contemplating the catastrophe as a fait accompli, rather than participating in any form of action. The living and the dead all share this static position, enhancing the impression that although only the firstborn were singled out for killing, the final plague meant the fall of an entire society. Any hint at dramatic commotion is relegated to the painting’s margins, where marginal characters are paradoxically allowed more agency: musicians, shaven-headed prostrate subjects—possibly priests—and, in the upper right-hand corner, Moses and Aaron themselves. The latter are not only the human vehicles of the disaster, but also, in the case of Moses, the ‘narrator’ who in Exodus 11 describes the coming plague and who here, as if proleptically, sees the consequences of his realized prophecy.

References

Mason, Peter. 2020. The Modernists that Rome Made: Turner and Other Foreign Painters in Rome XVI–XIX Century (Rome: Gangemi Editore)

Moser, Stephanie. 2020. Painting Antiquity: Ancient Egypt in the Art of Lawrence Alma Tadema, Edward Poynter and Edwin Long (New York: Oxford University Press)

Unknown artist

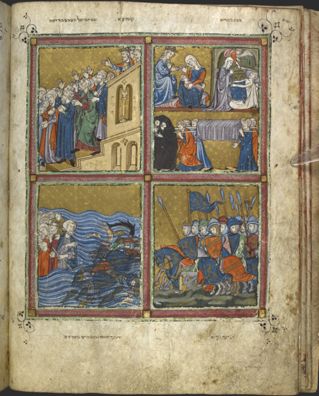

The Passover, from the Golden Haggadah, c.1300, Illuminated manuscript, The British Library, London; Add. 27210, fol. 14v, ©️ The British Library Board (Add 27210, f.14v)

Solidarities in Suffering

Commentary by Itay Sapir

In the fourteenth-century Golden Haggadah, made in Barcelona, eight folia, each displaying four framed images, accompany the text. The depiction of the tenth plague of Egypt, the killing of the first-born sons, is among the most complex of these illuminations, as it includes three separate episodes.

The upper right image (the first in the sequence, corresponding to the right-to-left direction in which Hebrew is read) shows a man on his bed struck by the Angel of Death, with what may be a mourning relative in attendance. In the second scene (to the left), a woman grieves for her seemingly dead baby, accompanied by another person (the British Library description suggests an inversion of roles, claiming that what we see is ‘the queen mourn[ing] her baby lying lifeless on a nurse’s lap’). It has been noticed that this is a very female-centred recounting of the story, as the mourners in the upper register are all women. The lower register is occupied by what is probably a funeral procession for the victims (although other interpretations have been proposed for that scene).

Interestingly, the episode on the upper right-hand side is framed by an architectural setting, giving it a more specific, anecdotal character—though in no way a ‘historical’ reconstruction of anything Egyptian—compounded by the attempt to point to the very instant of the man’s expiration, with the Angel of Death represented in the action of hitting the victim. By contrast, the other two sections, representing the aftermath of the killings, are universalized through an abstract gold-leaf background.

This is particularly striking for the ‘Pietà’ scene at the upper left, which is thus readable as a conflation between the Virgin and Child theme and the depiction of Mary holding her dead, adult child in her lap. This iconography emerged, in the Christian context, precisely in the second quarter of the fourteenth century (first with the German Vesperbild, which raises the question of its early dissemination as far as Barcelona). However, for scholars such as Marc Michael Epstein (2011), The Golden Haggadah, while resembling contemporary Christian illuminations, is a profoundly Jewish work. Jewish, but not parochial: the grief of the Egyptians is represented here with great human sensitivity, in spite of their role as villains in the Exodus narrative.

References

Epstein, Marc Michael. 2011. The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative, and Religious Imagination (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Tenth Plague of Egypt, c.1802, Oil on canvas, 143.5 x 236.2 cm, Tate; Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856, N00470, ©️ Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

The Darkest Prophecy

Commentary by Itay Sapir

While J.M.W. Turner is without doubt one of the most original and talented painters of the nineteenth century, it is arguably not from his ability as a storyteller that his fame derives.

His early work depicting the tenth plague of Egypt (there’s also a contemporary depiction of the fifth plague) is no exception, as the biblical narrative seems no more than a pretext for a dark, moody landscape. Dead children and grief-stricken mothers are depicted, and some blurry, distant groups of figures seem to engage in violence, but the complex demands of making an image of that specific story—one which both focuses on the death-event and its causes, and indicates that the victims are firstborn—are eluded.

Such reproach, for a painting included in the 1802 Royal Academy Exhibition to great critical acclaim, is perhaps not wholly deserved. A few scholars have noted Turner’s debt, in this work, to the French seventeenth-century painter Nicolas Poussin (a departure from his more usual homage to Poussin’s contemporary Claude Lorrain—considered, like Turner, much more competent with nature than with humans). Poussin produced many landscapes in which a small-scale narrative scene is almost hidden but is, nevertheless, both the key for the work’s meaning and an echo of the subtleties of nature’s mood. In a similar vein, Ian Warrell describes Turner’s painting as a ‘pictorial essay’ which ‘employs a particularly ferocious type of sublime imagery as a visual metaphor for God’s deadly retribution against the first-born sons of the Egyptians’ (2013: 103).

Undeniably, what Turner lacks in specific, narrative content, he compensates for with great sensitivity in the nocturnal mood of this biblical scene. His painting is perhaps, thus, particularly apt as an interpretation of Exodus 11, where Moses describes, as a future event, the most terrible of the plagues, rather than as a depiction of its actual occurrence in the next chapter. More than a concrete occurrence, the killing of the firstborn is here a dark prophecy, the ultimate demonstration of the omnipotence of the God of the Hebrews, and the comparably miserable, insignificant existence of humans.

References

Warrell, Ian (ed.). 2013. J.M.W. Turner: The Making of a Master (London: Tate)

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema :

The Death of the Pharaoh’s Firstborn Son, 1872 , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist :

The Passover, from the Golden Haggadah, c.1300 , Illuminated manuscript

Joseph Mallord William Turner :

The Tenth Plague of Egypt, c.1802 , Oil on canvas

A Fell Swoop

Comparative commentary by Itay Sapir

The tenth plague of Egypt, described in Exodus 11 ahead of its realization in Exodus 12, presents particular challenges to visual artists. While most other plagues suggest a distinct, concrete imagery, a specific representation of the Death of the Firstborn requires astute pictorial solutions.

First, in order to avoid confusion with other episodes of sudden, collective death, the artist needs ideally to make it clear that here the group of victims consists of firstborn sons and no one else. Second, the abrupt nature of the killing, occurring ‘about midnight’ and seemingly more or less in one fell swoop, has to be shown. The question of the temporality of death is a persistent problem for visual representation throughout history, and is acute here. When a death-event occurs within a larger narrative, how can an artist single out in a fixed image the very instant of death taking place, rather than showing either the premises and preparations for it, or a posterior moment with the deed done and the victims already lifeless?

Each one of the three artworks chosen for this exhibition deals differently with these difficulties; none succeeds in fully responding to all the admittedly challenging tasks. Regarding the management of temporality, the medieval Haggadah illumination, in a way that is typical of pre-Renaissance European imagery, unpacks the story into three autonomous-yet-contiguous episodes, of which only the first one aims at pinpointing the instant at which life ceases. The two nineteenth-century canvasses, on the other hand, choose to concentrate on the grief that ensues—dramatic in the case of J.M.W. Turner, restrained in Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s depiction. We don’t get to see, in these paintings, the precise moment at which God’s wrath hits the firstborn of Egypt. Instead, it is the psychological consequences of this event that are elaborated upon.

As for the need to show that the victims belonged to a very specific group: none of the artworks even tries to translate that fact into imagery, resulting in pictures that could in principle represent other mass killings. One could hypothetically imagine strategies that would be more explicit, such as showing a family with several sons and only the evidently oldest dead—but the three artists in this exhibition have chosen not to fuss too much about that specificity.

Nevertheless, through another aspect of temporality, the modern representations—Turner vaguely, Alma-Tadema much more rigorously—hint that what we see is in fact the tenth plague of Egypt: by the architecture, clothing, and objects depicted, they allude to an Ancient Egyptian setting.

These three images also express diverse choices in the depiction of various specific elements of the biblical text. As already mentioned, the tenth plague was inflicted at night-time. Turner seems to take that timing into account, even though he includes a (supernatural?) light which is too bright for a truly nocturnal setting. The Haggadah image ignores that indication altogether. And Alma-Tadema, opting for an interior scene, is less concerned by that issue, although glimpses of the exterior and the internal artificial lighting do suggest an adherence to the time-frame mentioned in Exodus 11.

As for the auditory element, which is another major challenge for mute images, our artworks also opt for diverging solutions. Turner is the most explicit in visually translating the ‘loud cry’ that was heard ‘throughout the whole land of Egypt’ (Exodus 11:6): not only do some of his grief-stricken figures clearly scream their pain, but also the whole cosmos seems to accompany them in ecstatic terror—the trees, the clouds, the odd bright light. Alma-Tadema is on the other end of the sonic spectrum: the only implied sounds are the music played (one imagines it soft and elegiac), and the sighs of the mother, suffocated as she hides her face between the dead son and the silent father. The medieval illumination lies somewhere midway: the mourners’ mouths are open, but their gestures indicate a rather restrained reaction to the horror they are witnessing.

Finally, the images differ in the gender roles they assign to their protagonists. Both Turner and the Haggadah illustrator choose the traditional female identity for the carriers of Trauerarbeit, the ‘work’, as Freud has it, of grieving. No less conservative perhaps, Alma-Tadema presents us with examples of both male and female mourning, reproducing the somewhat clichéd distinction between the Pharaoh’s dignified, pensive, and self-possessed sorrow and the mother’s powerless collapse.

Commentaries by Itay Sapir