1 Kings 8:14–61; 2 Chronicles 6:3–7:3

The Dedication of the Temple

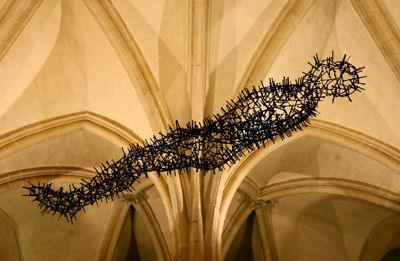

Antony Gormley

Transport, 2010, Iron nails, 210 x 63 x 43 cm, Canterbury Cathedral, England; © Antony Gormley; Photo courtesy of PA Images

The Body as Temple

Commentary by Christopher Irvine

Antony Gormley is well known for his body cases, frequently moulded from his own body, cast in plaster, and then finished in lead, or sometimes in steel, or even in concrete. The body, he once averred, was a temple of being (Hutchinson 2000: 34).

These sculpted forms appear in various postures. Some of them are standing, some sitting, and others crouching, and each of these postures articulates a particular attitude. The Chronicles account of Solomon’s prayer at the Dedication of the Temple not only tells of the bronze platform that Solomon installed in the outer court, but also adds the detail that it was there that he knelt to pray (2 Chronicles 6:13). Both the location and posture recorded here point to the question of our place, or of how we occupy sacred space.

Antony Gormley’s Transport is currently displayed in the Eastern Crypt of Canterbury Cathedral, where the body of Thomas Becket was buried after his brutal murder in 1170. The outline shape of the sculpture is undoubtedly that of the human body, but it is not a cast. It is fabricated by 210 nails welded together, and so there is no ‘skin’. The sculpture is perceptually open, and the viewer can see the whole, both inside and outside. Transport seems to defy gravity as it is suspended from the vaulted ceiling by a single steel wire. Further, because of the natural airflow caused by the fluctuating temperature of the environment in which it is set, the sculpture is often seen to rotate slowly. This gentle motion and the passing of air through the sculpture evoke a living, ambulant body that in-breathes the very breath of life.

Visitors are often surprised to see a contemporary sculpture in this resonant space of the cathedral, and some may question its congruence in the space. But returning to the image of Solomon at prayer, a more critical question is how we place ourselves before God. Every living person is embodied, and as such occupies and moves through space. And when an embodied person occupies the place where prayer is offered, the physical body itself can become a ‘laboratory of the spirit’ and our bodily posture an expression of unarticulated prayer.

References

Hutchinson, John. 2000. ‘Return (The Turning Point)’, in Antony Gormley, ed. by John Hutchinson, et al (New York: Phaidon), pp. 32–95

Richard Long

Tame Buzzard Line, 2001, Stones, New Art Centre, Roche Court, England; © Richard Long. All Rights Reserved, DACS, London / ARS, NY; Photo: ArtImage

Marking the Place

Commentary by Christopher Irvine

Whether it is the trace that is left through the grass of a field, or a line, a circle, or an ellipse of slate, or flint arranged in patterns on a gallery floor, the art of Richard Long is about marking and moving through space. Long’s Tame Buzzard Line is constructed with local flint stones and marks the straight flight path of a raptor to a fence from a tree standing alone in a field.

As Tame Buzzard Line traces a movement (however transient) through space, it also delineates space. Space is boundless and indeterminate, and it reaches out towards an ever-extending horizon. But in delineating space, the artist is indicating—even helping to create—the particularity of a place.

Likewise, in offering his prayer of dedication, Solomon is delineating the spaces of the Temple complex in Jerusalem to be a place: a place of prayer. And in the retelling of this incident in 2 Chronicles, the point is made that the Temple is not only a place where prayer is offered, but where it is received by God (2 Chronicles 6:39; 7:15).

Tame Buzzard Line records something specific, something that occurred in time and space: the buzzard flew here, in this direction, and between these two points. A buzzard can fly in all directions and at various heights, but in marking this flight in a line, Long is making a sacrament of stone, making visible the invisible flight path of the buzzard on one specific occasion.

King Solomon acknowledged that the divine cannot be contained, and that the divine Spirit roamed freely over the whole face of the earth (Genesis 1:2b; John 3:8 ‘the Spirit moves where it wills’). But God is here and there, and as a line marks a certain place and a circle creates a zone, so in the delineation and dedication of its different spaces, the Temple built of stone became a holy place. For although God is ubiquitous—a God who is everywhere and may be encountered anywhere—he is known in the place where his name is invoked, where the weight of his presence is felt, and where his glory is seen.

References

Wallis, Clarrie (ed.). 2017. Stones Clouds Miles: A Richard Long Reader (London: Ridinghouse)

El Greco

Christ driving the Traders from the Temple, c.1600, Oil on canvas, 106.3 x 129.7 cm, The National Gallery, London; Presented by Sir J.C. Robinson, 1895, NG1457, Photo: © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

Space for the Holy

Commentary by Christopher Irvine

Solomon’s dedication of the Temple was the designation of sacred space, and what El Greco shows in this painting is the reclaiming of space as holy place. It is a subject to which he returned throughout his career. In this canvas the scene is sharply focused, and the extraneous references are reduced.

The spatial composition and bold colouring of Christ’s robe place him centre stage. His eyes are fixed on the traders, and his taut body captures a moment before there is another lash of the whip of cords. In the foreground is the upturned table of one of the money changers. To the left is a group of traders. They flinch and raise their arms and hands to protect themselves. To the right a group of Christ’s disciples are puzzled and amazed in equal measure. The painting crackles with emotional energy, and, as such, contrasts with the scene evoked in the account of Solomon offering his prayer of dedication in the first Temple. Solomon is humble and suppliant; Jesus is strident and insistent. He forcefully clears space for an encounter with the divine. But this was not to be, as it was at the Dedication of Solomon’s Temple, in the form of fire and cloud (2 Chronicles 5:14; 7:1).

The painting shows a woman carrying a basket on her head, walking through a clear architectural space on the far right. This graceful figure moving purposefully through an uncluttered space may well be a personification of grace. For in the compositional arrangement, the woman balances the figure of Christ (they seem almost to walk in step), and contrasts with the basket carriers of the left who assert a transactional relationship with God.

In this portrayal of the driving of the traders from the Temple, Christ signals a new divine economy of grace, a currency that is minted through the fate of his body, crucified and raised on the third day. For when Christ referred to the Temple in speaking of it being destroyed and rebuilt, he referred, according to John’s Gospel, to his body (John 2:21).

References

Lopera, Jose Alvarez (ed.). 1999. El Greco: Identity and Transformation (Skira: Madrid)

Antony Gormley :

Transport, 2010 , Iron nails

Richard Long :

Tame Buzzard Line, 2001 , Stones

El Greco :

Christ driving the Traders from the Temple, c.1600 , Oil on canvas

God’s Dwelling Place

Comparative commentary by Christopher Irvine

A contemporary artist setting out to walk through a wild landscape might evoke in our imaginations the shadowy figures of the Hebrew Patriarchs, of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who set out across an expansive wilderness.

Richard Long often walks with a map to hand; the Patriarchs could only mark the journey they had made by erecting, here and there, stone altars to hallow those places where they were encountered by the God who could meet them at any time and in any location (Genesis 12:7). Once God’s people had settled in the land of promise, the monarchy was eventually established, and a Temple built.

There then followed the long succession of the kings of Israel, the division of the nation into Judah and the Northern Kingdom, and after that the sad displacement of the people and the destruction of the first Temple in Jerusalem in 585 BCE. These historical vicissitudes provide the narrative arc for the books of Samuel and Kings. But following the return from exile and the challenge to rebuild the Temple, a different perspective emerged. And as El Greco could paint the same subject in fresh compositional arrangements, so Israel’s history was retold from a different angle and with new emphases. The new narrative of the post-exilic period was 1 and 2 Chronicles (so named by Jerome), and the new emphasis was on the Temple—the physical building and its cult.

Given this emphasis, it is not surprising that some new material was woven into the story of King Solomon’s dedication of the Temple. As a parallel reading shows, the writer of Chronicles closely followed the earlier source, but the fact that so much material is carried over from Kings makes the editorial interest even more prominent. Two verses from Psalm 132 are included to herald what is presented as God’s answer to Solomon’s prayer at the Dedication of the Temple, the coming of God’s glory to dwell in the Temple (2 Chronicles 7:1–3). Acknowledgement is made that God cannot be contained in any built structure, and yet, God not only gives his name, but comes to occupy the Temple’s holy of holies.

The coming of God to his Temple is recalled by the dramatic action of Jesus entering and reclaiming the sacred space of the Temple precincts. As El Greco shows with such vigour and vibrancy, the action of Jesus in ‘cleansing the Temple’ demonstrated what the prophet had declared: ‘My house shall be called a house of prayer for all nations’ (Isaiah 56:7; Mark 11:17 and parallels). And the violent nature of the incident indicates the instability of the intended reciprocity between sacred architecture and the serious business of worship.

Despite the monumental scale of its architecture, there is a tension in what the Temple represented. It could all too easily be compromised, and, worse, contaminated. Historically its fabric did not automatically protect the people from calamity (e.g. Jeremiah 7:4), and so, unsurprisingly, the ambiguity about what constitutes a sacred place persists (2 Samuel 7:5–6; 2 Chronicles 6:18).

It was the rebuilt Temple of the returned exiles, further enlarged in 20 BCE by Herod the Great, in which Christ demonstrated his messianic status. Through this action, Christ can be seen as metaphorically making space for a new meeting between humanity and God’s grace, and it is this that El Greco shows in his depiction of the expulsion of the money changers from the Temple. In the new dispensation, as the first Christians understood it, there could be nothing transactional in the relationship between God and humankind. As foreshadowed by the account of the answer to Solomon’s prayer of dedication, it depends on the condescension of God becoming present for all people in the transforming beauty of the Spirit.

The installation of a contemporary sculpture in sacred space may surprise and possibly unsettle the viewer, with the question of where and how God dwells with humankind. God comes to his Temple in the embodied form of Jesus, the incarnate Word. And as St Paul transfers the trope of ‘the Temple’ to both the social body of the church and to the individual bodies of its members (1 Corinthians 3:16; 6:19), so the sense of the Spirit meeting and merging with the human spirit is most intensely felt on those occasions when Christians gather together ‘as stones being built into a spiritual temple’ (1 Peter 2:4; Ephesians 2:19–22) for shared corporate prayer.

Can God dwell in a temple? God has, and God also deems the human body a fit place to indwell through the Spirit.

References

Barker, Margaret. 1991. The Gate of Heaven: The History and Symbolism of the Temple in Jerusalem (London: SPCK)

Rae, Murray A. 2017. Architecture and Theology: The Art of Place (Waco: Baylor University Press)

Commentaries by Christopher Irvine