Zechariah 1

The Exalted Return to Jerusalem

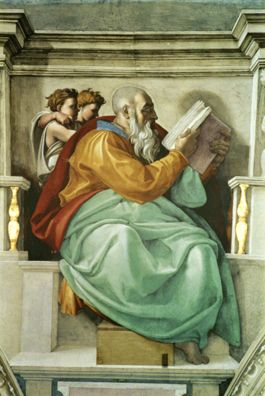

Michelangelo Buonarroti

Prophet Zechariah, 1508–12, Fresco, Sistine Chapel, Vatican City; Photo: Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

The Prophet

Commentary by Adrianne Rubin

Commissioned by Pope Julius II in 1508 to paint the ceiling frescoes of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo created a decorative scheme far different from that of the pope’s vision.

Before Michelangelo began work the vault of the Sistine ceiling was painted blue with gold stars, a ‘starry Heaven’ approved by Pope Sixtus IV at the time of the Chapel’s construction in the early 1480s (King 2003: 20). Julius II wanted representations of the twelve apostles to occupy the spaces between the eight spandrels and the four pendentives supporting the vault (ibid: 58). Instead, purportedly under the guidance of a theological advisor and with Julius II’s blessing, Michelangelo depicted twelve other figures—five female and seven male. Michelangelo felt his chosen subjects would afford him more opportunity to explore the intricacies of the human form (ibid: 59). The five females are sibyls of the classical world and the seven males are prophets from the Old Testament, including Zechariah (Hartt 1987: 492).

Although Zechariah is one of the shorter prophetic books (hence Zechariah's description as a ‘Minor Prophet’), the prophet is given pride of place on the Sistine ceiling, directly above its main entrance. He is highly visible from the altar at the opposite end—prominently in the line of sight of the Pope, for example, when he says Mass.

Each figure on the ceiling was intended to foretell an aspect of the life of Christ to the viewers of Michelangelo’s scheme. Zechariah 1, which centres on the return of the Jewish people to Jerusalem, can also be seen as a foreshadowing of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem, commemorated every Palm Sunday. Zechariah’s placement within the ceiling complex, above the doors that give access to the chapel, make him an emblem of triumphal entry.

Zechariah is portrayed as a vast, enthroned figure in flowing robes. Although young at the time of his prophecies, Michelangelo depicts him as a mature, white-bearded man, perhaps in deference to the wisdom of his writings. The figure of Zechariah, the personification of his book, is seen here holding that very book. Thus, his visions are made manifest.

References

Hartt, Frederick. 1987. History of Italian Renaissance Art (London: Harry N. Abrams)

King, Ross. 2003. Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling (New York: Bloomsbury)

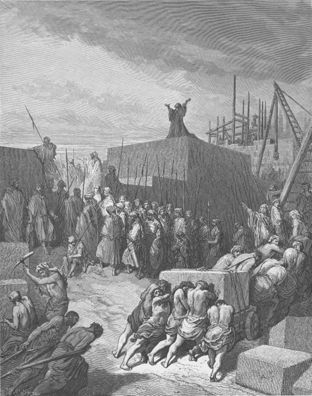

Gustave Doré

Re-building of the Temple in Jerusalem, from Doré Bible, 1866, Engraving; Photo: Wikipedia / Public Domain

The Reconstruction

Commentary by Adrianne Rubin

In Zechariah 1, as ‘the word of the LORD came to Zechari’ah…’, so did fantastical visions: prophecies of the rebuilding of the Temple.

I saw in the night, and behold, a man riding upon a red horse! He was standing among the myrtle trees in the glen; and behind him were red, sorrel, and white horses. (Zechariah 1:8)

In contrast to this dramatic, symbolic prophecy, which Zechariah may himself have found puzzling, Gustave Doré gives us an image of the concrete physical toil of reconstructing the Temple. The rebuilding is best foreshadowed in Zechariah 1:16, where an angelic messenger, a kind of intercessor between God and Zechariah, conveys this message to the prophet:

Therefore, thus says the LORD, ‘I have returned to Jerusalem with compassion; my house shall be built in it’, says the LORD of hosts, ‘and the measuring line shall be stretched out over Jerusalem.

Re-building of the Temple in Jerusalem was published in 1866 as one of 241 engravings created by Gustave Doré for La Grand Bible de Tours, the expanded edition of the 1843 French translation of the Vulgate known as La Bible de Tours.

Doré’s engraving conveys both the intense physical labour of rebuilding the Temple, and the exultation of having reached this moment, when the longed-for restoration finally occurs. The latter is most evident in the figure atop the Temple’s foundation with arms outstretched in awe and in gratitude to God. One can imagine this figure as the embodiment of the angel of the Lord standing among the myrtle trees in Zechariah 1:11.

Doré’s image depicts the fact that the supreme place of worship for the Jewish people, the Temple, is also the ultimate manifestation and emblem of God’s favour. Its reconstruction is confirmation of his promised intention to restore the Jewish people to Jerusalem.

‘[B]uild the house, that I may take pleasure in it and that I may appear in my glory’, says the LORD. (Haggai 1:8)

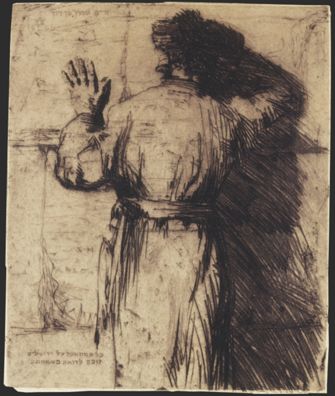

Hermann Struck

Everyone Who Mourns Jerusalem Reaps Its Joy (At the Wailing Wall), 1905, Lithograph on paper, 438 x 349 mm, The Jewish Museum, New York; Gift of Dr and Mrs George Wechsler, 1996-80, Photo: The Jewish Museum, New York / Art Resource, NY

The Last Vestiges

Commentary by Adrianne Rubin

The profound sense of promise that accompanied the rebuilding of the Temple as prophesied in Zechariah 1 has here been reduced to this image of a solitary man praying at the Western Wall—the last standing remnant of the Second Temple; the most sacred place in the entirety of Judaism.

With eyes covered in prayer, the man—perhaps the artist himself—touches the Wall in a dual act of physical and spiritual validation. The inherent emotional dichotomy is apparent: the grief over the destruction of the Second Temple—and the First—necessarily co-exists with the joy and gratitude over the continued presence of the Wall.

Hermann Struck, who was born to an Orthodox Jewish family in Berlin in 1876, would have had a keen awareness of all that has been lost. A member of the Berlin Secession, Struck emigrated from Germany to the Holy Land in 1922 (Gorelick 1994: 69).

The title of the print calls to mind Isaiah 66:10: ‘Rejoice with Jerusalem, and be glad for her, all you who love her; rejoice with her in joy, all you who mourn over her’. Unlike the passage in Isaiah, Struck’s title emphasizes the sadness first, yet it implies that the concomitant joy is inevitable. He embeds the inscription of the work’s Hebrew title in the bottom left of the print itself. This again emphasises how intrinsic these emotions are to the physical and spiritual experience of being present at the Wall, or even to the mere evocation of that experience, as mediated by the work.

The title also recalls Ezra 3:13, which states of the rebuilding of the Temple: ‘the people could not distinguish the sound of the joyful shout from the sound of the people’s weeping’. Then and now, these contrasting emotions cannot entirely be distilled from one another.

Struck’s image is the embodiment of Zechariah 1:17:

Cry again, Thus says the LORD of hosts: My cities shall again overflow with prosperity, and the LORD will again comfort Zion and again choose Jerusalem.

References

Gorelick, Ted (trans.). 1994. Hermann Struck, From Berlin to Haifa: Etchings (Haifa: Mané-Katz Museum)

Michelangelo Buonarroti :

Prophet Zechariah, 1508–12 , Fresco

Gustave Doré :

Re-building of the Temple in Jerusalem, from Doré Bible, 1866 , Engraving

Hermann Struck :

Everyone Who Mourns Jerusalem Reaps Its Joy (At the Wailing Wall), 1905 , Lithograph on paper

The Endurance of Faith

Comparative commentary by Adrianne Rubin

Deliverance, faith, and restoration lie at the heart of Zechariah 1.

The initial chapter of the book centres on the return of the Jewish people to Jerusalem after having been in Babylonian exile following the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE by Nebuchadnezzar. The desolation of the decades-long exile ended in 538 BCE, when Cyrus the Great, a Persian conqueror of Babylonia, permitted—even encouraged—the Jews to return to the land of Judah to rebuild God’s house in Jerusalem. After a call to repentance, Zechariah 1 focuses on God’s intention to fulfil his covenantal promises to the Jewish people. The return to Jerusalem and the rebuilding of the Temple are inextricably linked and are pre-conditions for the coming of the Messiah.

The building of the Second Temple began during Ezra’s period, and after having been stalled and then halted altogether for years, resumed during the time of Haggai and Zechariah. Along with the physical restoration to the land and the toil of rebuilding the Temple came the spiritual renewal and the accompanying rebirth of faith. God had not forsaken the Jews. Rather: ‘“Return to me…and I will return to you” says the LORD of hosts’ (Zechariah 1:3). The physical and spiritual necessarily co-exist.

The artworks selected for this exhibition, whether explicitly or obliquely, visualize faith. Viewing them together, we may progress from Michelangelo’s depiction of Zechariah, whose prophetic legacy is imbued with faith and the hope of salvation, to the Temple whose reconstruction (depicted by Gustave Doré) is the manifestation of the text’s stated promise. Hermann Struck’s lithograph depicts the archetypal act of faith in Judaism—prayer at the Western Wall. It also conveys an implicit sense of the hope that endures as long as any remnant of the Temple exists and is used for worship by even a single, solitary figure.

Michelangelo’s Early Modern fresco is executed in vivid colour and on the grand scale befitting a prophet. It is meant to be beheld from a distance, inspiring awe. The distinctive colours Michelangelo chose may echo the significance of colour in Zechariah’s visions, where ‘red, sorrel, and white horses’ feature prominently (Zechariah 1:8).

The two prints are, unsurprisingly, monochromatic, comparatively small, and intended for close viewing. The extensive, almost journalistic, detail of Doré’s nineteenth-century engraving contrasts sharply with the early-twentieth-century lithograph by Struck, which is intimate, and all the more emotionally potent for its relative simplicity.

While Zechariah’s visions are bizarrely dramatic (featuring horses patrolling the earth and horns being struck) the work by Doré is striking for other reasons—for the sheer scale of what is portrayed in a book-sized print. It features a cast of dozens, with many more figures easily imagined beyond the proverbial frame, undertaking a monumental, historic task. It epitomizes the concrete materiality of Zechariah’s prophecies.

Struck, on the other hand, highlights the isolated act of prayer, even if it takes place amongst other people. Struck surrounds his subject with bold hatch marks on the right side, a deliberate feature that harks back to earlier printmaking techniques and which serves to create a sense of inseparability between the figure and the Wall. This figure represents the human thread of continuity from Zechariah’s day to Struck’s own. The prayers uttered at the Wall remain unchanged, and the human presence at this holiest of Jewish sites remains integral to its being and indeed its raison d’être.

What these three otherwise disparate works of art share in common is that each in its own way illustrates the concretization of Zechariah’s prophecies as described in Zechariah 1. Michelangelo’s fresco portrays Zechariah holding his book—the physical record of his prophecies. Doré’s print—which in its ordered rationality contrasts sharply with the wild, fantastical nature of Zechariah’s visions—shows the physical structure of the Second Temple coming into being, as alluded to in the text. Struck’s lone worshipper—who may serve as an emblem of Zechariah himself, of the artist, or merely of an archetypal Jewish man—touches the last remnant of the Second Temple. The figure and the Wall mutually reaffirm each other’s continued existence.

In each work, the visions of Zechariah are the precursor and the inspiration for the material realities created. Each also expresses the theme of enduring faith that pervades Zechariah 1, as ultimately, faith finds expression in material forms, which in their turn act in service of continued faith.

Commentaries by Adrianne Rubin