1 Peter 2:11–25

Examples of Suffering

Unknown Congolese artist

Bowl-Bearing Figure, 19th Century, Wood (Ricinodendron rautanenii), Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium; Collected between 1981 and 1912, gift of A.H. Bure, EO.0.0.14358, Photo: J.-M. Vandyck, © RMCA Tervuren (CC BY 4.0)

A Royal Priesthood

Commentary by Katherine Sonderegger

This remarkable sculpture expresses in gesture, solemnity, and tensile dignity the royal priesthood the author of 1 Peter recognizes in a persecuted community. The woman depicted kneels with an empty bowl. Her gaze is lowered, eyes turned inward and slightly closed. Apart from her royal headdress, she is unclothed, her torso and limbs slender, agile.

The art of the Luba people frequently depicts women in poses of quiet strength, bearing up thrones or carrying vessels, always self-contained and with great reserve.

Just so we might image the community addressed by the author of 1 Peter. The letter admonishes and encourages a young Church which has tasted suffering and bitter trial, suspicion by its neighbours, and accusations of unnamed evils. Throughout the letter we read of suffering—and the dignity that is uncovered in bearing suffering quietly, patiently, confident that in suffering for what is right, a believer will ‘have God’s approval’ (1 Peter 2:20). These are the rejected ones—‘living stones’ (2:5), 1 Peter calls them—who will become corner stones; ‘no-people’ who will become a royal priesthood, a holy nation, precious to the Lord. That this sculpture emerged from the Congo during the nineteenth-century imperial despoliation of central Africa bears powerful testimony to human dignity, resolve, and agency under persecution: a holiness shining in the midst of a night of wrong.

1 Peter is often thought to teach subservience, or worse, a pious devotion to suffering under unjust abusers. A deeper reading uncovers the royal office that is extended to the voiceless: to the enslaved who must serve the master who owns them, whether just or unjust; to wives who must obey husbands, whether loving or cruel; to those who are slandered who can rely on no public vindication. These are the ones 1 Peter calls a royal household, a temple built of living stones, a community radiating with holiness, chosen and precious before the Lord.

Under imperial domination, subject-peoples must find a foundation and a strength that cannot come from the culture in which they live; it must come from beyond. 1 Peter calls his persecuted church ‘aliens and exiles’: they live under colonial rule, their neighbours a source of danger or betrayal, yet they find another homeland in which they live ‘as free people’ (2:16). This is the citizenship of heaven that makes survival possible, even rich, in an earthly realm where endurance is the only daily lot.

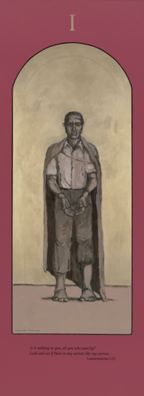

Margaret Adams Parker

Ecce Homo, from the Stations of the Cross, 2019, Paint and vinyl letters on birchwood panel, Collection of the artist (?); © Margaret Adams Parker

‘He Himself bore our sins’

Commentary by Katherine Sonderegger

Margaret Parker’s striking depiction of Christ brought before the people—the Ecce Homo—viscerally combines grandeur with vulnerability and sorrow. The figure of Christ is portrayed in modern dress, but is surmounted with a threadbare royal robe, the tribute by his abusers that both mocks and discloses the truth. The head bears the crown of thorns, and the hands are bound. The clothing shows a night of terror in police custody, and the feet are unshod, defenceless.

Yet the body of Christ is erect, facing us—we who are now the people assembled before Him. Meanwhile behind Him—depicted as He is with a palette of browns that underscore the poverty assumed by the Word—is shimmering gold. Parker renders the face of Christ with solemnity and strength; His eyes meet ours directly, the Judge, judged in our place (Barth §59.2).

The suffering of Christ takes on special urgency and pathos in the letter of 1 Peter. The persecuted Church undergoes a ‘fiery ordeal’ (4:12); it stands under judgement, which begins with the household of God (4:17), and the Adversary prowls even now like a ravening lion.

In the midst of this suffering, Christ stands as the Dying One who lives. There is no attempt to avert our eyes from the injustice and cruelty of this world, visited upon Christ and assumed by Him. The living enactment of the Suffering Servant psalms takes centre stage. Christ is mute, like a lamb before its shearers; He is poured out like wax; He is condemned among criminals; He makes the grave His bed. He bore our sins, the Righteous for the unrighteous.

The oppressed know this Christ; He knows them. In their suffering, He remains their ‘Shepherd and Guardian’ (2:25). In the midst of all that binds them, He frees. In the midst of all that wounds and afflicts them, He heals. In His own earthly pilgrimage, Christ entrusted Himself to the ‘One who judges justly' (v.23). 1 Peter does not leave oppression unchecked, nor take the hope of the poor away. Rather, as Christ Himself knew the God of justice, so those who are called into His way know that God is not mocked.

Yet into a fallen world, suffering will come, and for the persecuted, Christ will come as Exemplar, as Healer, as Righteous Judge. Parker’s Ecce Homo captures this pathos and this majesty.

References

Barth, Karl. 1956. Church Dogmatics 4.1, trans. by G.W. Bromiley (Edinburgh: T&T Clark)

Unknown Roman artist

The Dying Gaul, c.230–20 BCE, Marble, Musei Capitolini, Rome; © Vanni Archive/ Art Resource, NY

Endurance of the Subaltern

Commentary by Katherine Sonderegger

The sculpture depicts a warrior in his final battle with death, striving even now to endure and to fight on. His legs have failed him, and only one arm keeps his torso upright. His face is turned from us, absorbed in this last fatal struggle. The composition is self-contained, and even in the torque of the posture, the stillness and authority of the figure is maintained. This is suffering borne with dignity.

1 Peter tells us of peoples like the Gauls: the underside of empire, whose suffering is remembered only fleetingly, in tributes intended to honour the victors, or in letters to a persecuted minority which boldly address slaves and wives directly. The suffering of the subaltern remains hidden among the elites, as Antonio Gramsci noted in his daring essays on the marginalized in the new Soviet Union (Gramsci 2021). Yet the strength and endurance of such sufferers can still speak.

1 Peter addresses them as those who follow Christ’s example, hallowed and dignified by their likeness to their suffering Lord. This is not a romantic vision of the subaltern: 1 Peter recognizes that slaves and, later in the letter, wives do not exist in Adamic purity. Their actions, too, partake of the ambiguity and sin of the world east of Eden. But when they suffer for the right, their lives shimmer with the holiness of the true Subaltern, the Homo Sacer (Agamben 1998), whose life was taken, yet still He gave His life as a ransom for the many.

1 Peter famously evokes the duty to honour the emperor (2:17), and to respect the ‘authority of every human institution’ (v.13). This has been broadly taken as an endorsement of imperial power, and a recommendation for subservience to injustice. But again, a deeper reading serves us well here. The duty and obedience urged on the sufferers by 1 Peter has revolutionary effect: it will silence the oppressors (v.15). Like the Dying Gaul, their dignity even in death has the power to win respect from the victors, for in doing right, they are ‘blessed’.

Always these early believers must be ready to ‘give an account of the hope that is in them’ (3:15), for they do not fear what their oppressors fear, nor are they intimidated. For Christ who has been raised and exalted, sits now at God’s right hand, all authorities, powers, and angels subject to Him (3:22).

References

Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. by Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press)

Gramsci, Antonio. 2021. Subaltern Social Groups: A Critical Edition of Prison Notebook 25, ed. and trans. by Joseph A. Buttigieg and Marcus E. Green (New York: Columbia University Press)

Unknown Congolese artist :

Bowl-Bearing Figure, 19th Century , Wood (Ricinodendron rautanenii)

Margaret Adams Parker :

Ecce Homo, from the Stations of the Cross, 2019 , Paint and vinyl letters on birchwood panel

Unknown Roman artist :

The Dying Gaul, c.230–20 BCE , Marble

Empire and its Discontents

Comparative commentary by Katherine Sonderegger

How does one live under empire? Of course we know the answer to this question if we belong among the elite. Just this is the privilege of those on the sunny side of power—to barely see its outlines, to succeed at all its thresholds, and to enjoy its fruits.

The reckoning with racism that many white people faced in the United States in 2020 in the form of protests at the murder of George Floyd afforded a glimpse to the governing class of life far from these sun-lit corridors. Those on the underside of empire—the ones Antonio Gramsci called the 'subalterns'—of course knew these hard facts long ago. They knew the 'double consciousness' that W.E. Dubois diagnosed as the psychic agility and burden of being Black in a white, racialized society.

Dubois himself lived such a double life, the life of the subaltern. He moved within elite circles of white society, and found a place, though always a secondary one, within the white intellectual elites. Like any subaltern within a colonizing society, Dubois learned the language, customs, anxieties, and aims of the hegemonic classes. But he also learned how to move within a segregated society, crossing the colour line back and forth, belonging yet alienated within his own culture. Subalterns knew that life demanded of them a profile acceptable to white culture and an inner and collective resistance to the contempt it showered on them. An accurate analysis of those who rule, and a confident preservation of a reserve that retains the tang of the human—this is the life-long task of the subaltern.

The author of 1 Peter also knew this double world. It is a letter filled with the frank acknowledgement of forms of imperial and household power in the Roman world. And it knows that disciples in this young Church face slander, abuse, and danger from the gentiles who know the old religion and suspect these new dissenters in their midst. Martyrdom is never far off. This new religion is populated by wives, widows, and slaves; a miserable lot. Every day these disciples must navigate the deep: where to speak and where to keep silent? When to suffer abuse, when to resist or leave or plead for one’s life? 1 Peter speaks to those persecuted ones directly, not in a kind of ventriloquism through the master or paterfamilias. To these oppressed, the letter writer says: You are a royal priesthood, a holy nation, the Lord’s own possession! In truth, your own courage under suffering will serve as testimony to your slanderers, for it speaks with special power of the One who was judged a criminal, and hanged like a slave outside the city wall.

The artists in this series know this double reality of suffering and of dignity. They all speak of an inner reserve of strength called upon in the midst of exploitation, warfare, and state violence. These are not victims! The Buli Master shows a woman of special dignity and solemnity, a figure carved during the European despoliation of Central Africa. The celebrated sculpture of the anonymous figure known only as the ‘Dying Gaul’ manifests a vitality as life ebbs away—a victor in his own death. The Ecce Homo by living artist Margaret Adams Parker depicts the One who heals and delivers through His own victorious suffering, a Homo Sacer who can be thrown away by a simple wash of the hands. Yet His compassion and triumph remain unmistakeable in the midst of His night of interrogation, beating, and ridicule.

This is how to live under empire; Scripture teaches us how and these artists depict its contours.

References

Gramsci, Antonio. 2021. Subaltern Social Groups: A Critical Edition of Prison Notebook 25, ed. and trans. by Joseph A. Buttigieg and Marcus E. Green (New York: Columbia University Press)

Milbank, John. 2003. Being Reconciled: Ontology and Pardon (London: Routledge Press, 2003), esp. chps 5 & 6

Commentaries by Katherine Sonderegger