Genesis 3:22–24

Expulsion and Exile

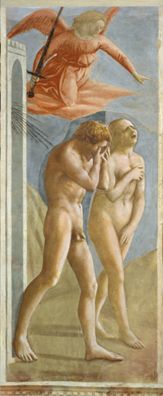

Masaccio

The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, c.1425, Fresco, The Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence; Scala / Art Resource, NY

‘The Woman Wailed’

Commentary by Elizabeth S. Dodd

The old English poem ‘Genesis A’ describes Eve’s departure from Eden thus:

The woman wailed, lamenting her loss,

Reproaching herself, repenting her choice.

(lines 853–4, Williamson 2017: 59)

The Genesis account is sparse and factual but the Florentine painter Masaccio, like the anonymous Anglo-Saxon poet, imagines the human emotion of the moment of exile. His rendering of the pair’s postures has been compared with ancient sculptures of the curly-haired satyr, Marsyas, and the contraposto stance of the Venus Pudica (modest Venus). However, the beauty of ancient forms is here transfigured by the intensity of human suffering, expressed in the covering and exposing of face and body. At this stage in the story the couple were already clothed (Genesis 3:21) (and for a while in the fresco’s history they were also modestly covered by the addition of vine leaves), but their visible nakedness here adds to their exposure and vulnerability. There is degradation and despair in Eve’s expression, her open mouth emitting a silent wail.

Masaccio’s Adam and Eve are united in exile but separated by it. They walk in step and their bodies overlap, but their physical gestures are in direct contrast to one another, particularly in the positioning of head and hands. Time has discoloured the blue background, bringing into view a subtle line between the two figures. This is an unforeseen result of the fresco technique, their having been painted on separate days (giornate) on to the wet plaster. Nevertheless, this long-term effect now highlights the separation between the figures. (It is a separation that will be echoed and expanded centuries later by Damien Hirst in his placing of Adam and Eve in separate Perspex boxes; see An Autopsy of the Fall, also in this exhibition).

Exile in this interpretation is separation. It is a distance between the pair that for existentialist theologians would come to express the human sense of alienation from ourselves (Kierkegaard 1980). In this image we see the paradox of loneliness as a shared experience.

References

Kierkegaard, Soren. 1980. The Concept of Anxiety: A Simple Psychologically Orienting Deliberation on the Dogmatic Issue of Hereditary Sin, trans. by Albert B. Anderson and Reidar Thomte (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Williamson, Craig (trans.). 2017. The Complete Old English Poems, The Middle Ages Series (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press)

Richard of Haldingham and Lafford [Richard de Bello]

Hereford Mappa Mundi, c.1300, Vellum, 158 x 133 cm, Hereford Cathedral, UK; Hereford Cathedral, Herefordshire, UK / Bridgeman Images

Mapping Paradise

Commentary by Elizabeth S. Dodd

Medieval Christianity interpreted the story of Eden through various mythologies and folk traditions. Some are represented in this monumental map of the world, which dates from around 1300 and still hangs in Hereford Cathedral.

The assumption that Eden was a geographical place meant that it was logical for it to appear on maps, but where do you locate paradise? Some suggested that Eden was lost in the flood (Genesis 6–9), others that it had been taken up into heaven. Here the lost paradise remains on earth, but any explorer endeavouring to find it would clearly be frustrated. The biblical text suggests that Eden was in the east (Genesis 2:8) and so it is here. East is at the top of the map, and so we see Eden in the uppermost inscribed circle, directly below the figure of Christ in majesty.

But medieval maps were more than geographical guides. They were symbolic representations of salvation history, of time represented through place, experience through picture.

In his commentary on Genesis, Claus Westermann notes that the Eden story has two endings. The exile happens twice: first in Genesis 3:23, ‘the Lord God sent him forth from the garden’; second in 3:24, ‘He drove out the man’. Westermann (2004: 27) attributes this to two oral traditions, patched together in the final written form.

But this double expulsion also gives the sense of a definitive ending. Its finality is echoed in this image of the lost Eden, triply blockaded: first by (a now slightly discoloured) sea; second by a ring of fire represented by curving red lines; and finally by a crenellated wall that transforms the garden into a fortified castle.

Eden after exile is utterly inaccessible, and yet its inclusion on the map makes it simultaneously tantalizingly present. The gap between earth and Eden is a narrow strait, whose closeness only strengthens humanity’s desire to reach the paradise that has been lost. Where there is desire there remains a hope of return. There is no exile without such yearning.

References

Scafi, Alessandro. 2006. Mapping Paradise: A History of Heaven on Earth (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

The Mappa Mundi, Hereford Cathedral: https://www.themappamundi.co.uk [accessed 1 August 2018]

Westermann, Claus. 2004. Genesis, trans. by David E. Green (London: T&T Clark)

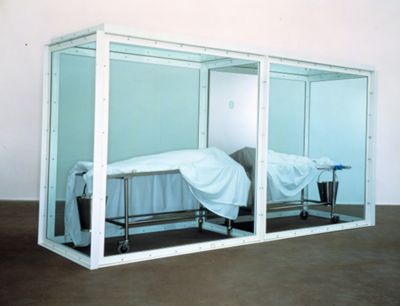

Damien Hirst

Adam and Eve (Banished from the Garden), 1999, Glass, painted steel, silicone rubber, autopsy tables, drainage buckets, mannequins, chicken skins, autopsy equipment, cotton sheets, surgical instruments, needle and thread, latex gloves, and sandwich, 221 x 426.7 x 121.9 cm, Location unknown; © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved DACS / Artimage, London and ARS, NY 2018. Image courtesy of Gagosian Gallery. Photo: Mike Parsons

An Autopsy of the Fall

Commentary by Elizabeth S. Dodd

This installation was selected for a 2004 Tate ‘Britart’ exhibition, whose purpose was to explore ‘the contemporary consequences of the original myth of falling from grace’ (Tate Britain 2004). In Genesis 2:17, death was the threatened result of disobedience. Here, Damien Hirst seems to present the promise as promptly fulfilled, as Adam and Eve lie separately stretched out under sheets on autopsy tables. The stark scientific materialism of cold metal can be interpreted as a no-nonsense statement that exile = death.

Hirst’s artwork might be said to particularly resonate with the strand of the Genesis story expressed in 3:22, which sees humanity barred from immortality as represented by the tree of life. It cuts through some gentler interpretations in recent Christian exegesis which, influenced by early Christian sources, can soften the curse of Adam and Eve by emphasizing the Lord’s ongoing grace and providence even in their banishment (Irenaeus Against Heresies 3.23; Von Rad 1970: 97). I would argue that Hirst’s piece suggests a return to a previously more dominant Western Christian reading of the passage (often associated with Augustine) where the consequences of primal disobedience are a terminal catastrophe, without the intervention of the Lord through redemption in Christ (Augustine Confessions 5.9).

This installation could be understood as a commentary on Western culture as an autopsy of the Fall. It appears to hint at unfinished work. Used gloves are discarded in a corner of the table along with a disorderly collection of clinical instruments (including, chillingly, a saw), as if left by a careless pathologist. Are we still trying to figure out where it all went wrong by rummaging through the carcass of a dead mythology? How far can such investigation take us?

At first glance, the installation bears little resemblance to conventional representations of the exile narrative in the history of Christian art, and yet it can be interpreted as engaging deeply both with the story of Genesis 3:22–4 and with the artistic, theological, and cultural traditions that have emerged from it. In the light of this broader history, the autopsy motif might suggest the persistent niggle of a riddle to be solved, a mystery to be uncovered, a loss to be understood, and perhaps a wrong to be righted.

References

Augustine. Confessions. 1955. Trans. by Albert C. Outler, available at http://www.ccel.org/ccel/augustine/confessions.i.html

Irenaeus. Against Heresies. 1885. Trans. by Alexander Roberts and William Rambaut, in The Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 1, ed. by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing)

Rad, Gerhard Von. 1970. Genesis: A Commentary, trans. by John H. Marks (London: SCM Press)

Tate Britain. 2004.‘Visions of the Garden of Eden: Angus Fairhurst, Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas’, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/gadda-da-vida/gadda-da-vida-visions-garden-eden [accessed 1 August 2018]

Masaccio :

The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, c.1425 , Fresco

Richard of Haldingham and Lafford [Richard de Bello] :

Hereford Mappa Mundi, c.1300 , Vellum

Damien Hirst :

Adam and Eve (Banished from the Garden), 1999 , Glass, painted steel, silicone rubber, autopsy tables, drainage buckets, mannequins, chicken skins, autopsy equipment, cotton sheets, surgical instruments, needle and thread, latex gloves, and sandwich

In-A-Gadda-Da Vida

Comparative commentary by Elizabeth S. Dodd

Artistic interpretations of the expulsion from Eden often evoke an experience of exile. Adam and Eve are depicted chased, chastened, and bowed down. But they are also walking onwards towards a new future. The duality of this experience is expressed at the close of John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1674):

The world was all before them, where to choose

Their place of rest, and Providence their guide:

They, hand in hand, with wandering steps and slow,

Through Eden took their solitary way.

In Christian tradition, human life on earth has often been imagined as a kind of exile between the paradise of Eden and the joys of heaven. Artistic depictions of the story end-and-beginning of Genesis 3:23 present a moment of transition that marks all of human history.

As literary critic Stanley Fish has argued, one result of the Fall is that Adam and Eve’s vision of Eden is thereafter coloured by sin (Fish 1998: 140). The fallen pair are in part exiled from Eden because they can no longer see it—guilt struggles to understand innocence. Similarly, the artworks chosen here reflect a banishment from the garden so total that the memory of what has been lost is forever changed. Eden is viewed always from the perspective of exile, just as we might remember a childhood left behind, a home that has been lost or a happiness we do not expect to return.

Damien Hirst’s installation appeared in the 2004 Tate Britain exhibition ‘In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida: Visions of the Garden of Eden’. The title is that of a 1968 song by the rock band Iron Butterfly. The story goes that in the writing of the song, drunken slurring transformed the phrase ‘in the Garden of Eden’ into a nonsense lyric. It is as though those banished from Eden cannot even speak its name without distortion, and so in Hirst’s artwork the only hint of a life left behind can be seen in the suggestive drainage buckets and, more explicitly, some grisly rags of discarded flesh.

The medieval Mappa Mundi represents Eden as the moment of the Fall frozen in time and space, endlessly re-encountered with each viewing, unforgettable and inescapable. By contrast, Masaccio’s Eden is so inaccessible as to be virtually invisible. The fresco adorns a pillar, and because the painted archway through which the pair have walked marks the outer edge of that pillar, then beyond that archway there is nothing but empty air. The only hints of Eden are the stark lines of radiance emanating through the arch from the invisible ‘other side’. Once silver, they have tarnished and turned black over time, so that today they seem visually to echo the banishing angel with his now equally tarnished sword.

The depth of loss that this text invites us to explore is all the more extraordinary because it is not unredeemable. Though Hirst seems to stop short of suggesting any such redemption, in the other two artworks discussed there is some expression of hope.

The Mappa Mundi is made up of a series of enclosed circles, of realms that touch but will never meet. The outer circle of the earth encloses within its bounds the circle of Eden, but also just adjacent to it the upside-down devil enclosed in his own circle of hell. The two circles—the circle of hell and the inner circle of the earth—just overlap at the point where evil penetrated the world. To a contemporary eye there is a visual echo here of the meeting of ovum and sperm. The imagery of insemination takes us back to Augustine and his ideas about original sin (Ramsey 2008: 179). But the boundary between hell and Eden is preserved by a double line, while the devil remains within his sphere. Perhaps this suggests that while evil may be in the world, it will never be of it.

And while Adam and Eve are walking away from Eden in Masaccio’s fresco, they are also walking in the direction of the chapel’s altar: towards Christ and a history of salvation. Their shadows stretch behind them as—in the dawn of human history—they walk towards the east and the son of righteousness.

Artistic representations of the expulsion from Eden capture a moment of trauma and transition. The angel’s pointing finger, seen in Masaccio’s fresco, is a common trope that often points downwards in condemnation, but can also be seen as a sending forward and a sending out. Exile marks human experience, but in dwelling upon it we are invited also to look forward to a new hope.

References

Fish, Stanley Eugene. 1998. Surprised by Sin: The Reader in Paradise Lost (Cambridge: Harvard University Press)

Milton, John. 2008. Paradise Lost, ed. by Stephen Orgel and Jonathan Goldberg (Oxford: OUP)

Ramsey, Boniface (trans.). 2008. ‘Letter 37, To Simplician’, Book 1, Question 1, 10, in The Works of St Augustine: Responses to Miscellaneous Questions, vol. I/12, ed. by Raymond Canning (New York: New City Press)

![Hereford Mappa Mundi by Richard of Haldingham and Lafford [Richard de Bello]](https://images-live.thevcs.org/iiif/2/aw0181_richard-of-haldingham_hereford-mappa-mundi.ptif/full/!400,396/0/default.jpg)

Commentaries by Elizabeth S. Dodd