Hosea 2

Gomer and Hosea

Alison Saar

Sweet Magnolia, 1993, Ceiling tin on wood with magnolia leaves, 198 x 114.9 x 97.8 cm, Private Collection; © Allison Saar, courtesy of the LA Louver, Venice CA

Gomer, My Sweet Magnolia

Commentary by Wei Shieng Chieng

Sweet Magnolia features a naked African American woman figure carved from wood, overlaid with tin. Surrounded by actual magnolia leaves, her body merges with the land/tree roots, becoming a magnolia tree.

Sweet Magnolia also recalls Billy Holiday’s song Strange Fruit, with its haunting lines in which the scent of magnolias, ‘sweet and fresh’, is suddenly followed by the smell of ‘burning flesh’. The magnolia tree, after all, is not only the official state tree of Mississippi, but both tree and state were sites where African Americans were lynched.

In Hosea 2:3, 9–10, this intimate connection between the female body, nakedness, and land similarly takes on an uneasy tone underlain by violence. Gomer, a woman who is at once whore, wife of God’s prophet Hosea, mother of Hosea’s three children, and a metaphor for Israel, is threatened with impending punishment by being stripped naked, ‘turned into a wilderness and parched land’, and killed by thirst. This threat of stripping her involves violence and humiliation, and occurs thrice in Hosea 2.

The spiritual/religious infidelity of Israel is literally fleshed out by a dogged focus on the female body. ‘Whoring mother’ and ‘whoring land’ are amalgamated. Alison Saar’s female figure can intensify our appreciation of the vividness of this amalgamation. The fallen leaves of Sweet Magnolia point to parched surroundings, like those of the desert where Gomer awaits her fate. And Sweet Magnolia’s allusion to sites of lynching can also heighten our awareness of the violence against Gomer’s naked body, threatened as it is with an agonizing, slow death through thirst (v.3).

Sweet Magnolia’s female figure stands with one of her hands half-shielding her genitals, as if in response to God exposing her nakedness. The posture of her hand and fist, together with her tilted head (her eyes seeming to look heavenward), may suggest to us here the silent/ced Gomer—a Gomer questioning the violence inflicted on her. As a site of violence, Gomer begs the uneasy question of why a call for the religious reform of God’s people should take the form of such a physically explicit punishment inflicted on a woman’s body.

References

Dallow, Jessica. 2012. ‘Departures and Returns: Figuring the Mother’s body in the art of Betye and Alison Saar’, in Reconciling Art and Mothering, ed. by Rachel Epp Buller (Abingdon: Ashgate), pp. 57–70

Lynskey,Dorian. 2011. ‘Strange Fruit: The First Great Protest Song, 16 February 2011’, www.theguardian.com, [accessed 10 May 2019]

Anita Dube

Silence (Blood Wedding), 1999, Human bones covered in red velvet with beading and lace, 13 elements; dimensions variable, Devi Art Foundation, India; © Anita Dube, Courtesy of Nature Morte, New Delhi

You Will Call Me, ‘My husband’

Commentary by Wei Shieng Chieng

Silence (Blood Wedding) by Indian artist Anita Dube comprises thirteen sculptures. Dube used real human bones and meticulously sheathed them with blood-red velvet (a colour traditionally worn by Indian brides), further embellishing them with beads, sequins, lace, and embroidery, and enclosing each individually within a plexiglass case. While the bones are given a new life by the way they are lovingly endowed with artistic beauty, the work is nevertheless haunted by the silence of death.

Contradictories are here juxtaposed: both death and (second) life, both physical pain and aesthetic pleasure, both feminine coquetry and female disfigurement. By contrast with the language of ‘happy endings’ that is often associated with weddings, Silence (Blood Wedding) alludes to the complexities of certain traditional marriage customs (Andrews 1998: 84), and can be read as conveying an air of dark foreboding between the wife and the husband.

These embellished bones, when read together with Hosea 2:13, parallel Gomer’s coquetry, decking ‘herself with her ring and jewellery’, going after her lovers, and forgetting the Lord. At the same time, just as Dube lovingly draws the bones into new life through beauty, the Lord now intends to lure Gomer/Israel back to himself, wooing and speaking tenderly to her as he did in the past (v.14), so that she may call him ‘my husband’, and so that he may take her as his betrothed ‘for ever’ (vv.16, 19–20).

The tension however, is that Gomer is allured into the wilderness (v.14). An image is conjured not only of a place of forgiveness and reconciliation but also of a site of cruelty (punishment, abandonment, and death by thirst as in verse 3). The wilderness is the setting for both nightmare and second honeymoon, intended murder and seduction, and an unknown final fate. Gomer is further silenced, responding as though with love to God only in the words he puts into her mouth in this scripted interaction. An ominous tension hangs in the air. It lingers both over this reconciliation, and—as we let this image of Silence (Blood Wedding) accompany our reading of Hosea 2:13–20—over Gomer’s future in such a silenced marriage.

References

Andrews, Jorella G. 1998. ‘Telling Tales: Five Contemporary Women Artists from India’, Third Text, 43: 81–89

Sherwood, Yvonne. 1996. The Prostitute and the Prophet: Hosea’s Marriage in Literary-Theoretical Perspective (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press), pp.115–149

Sircar, Anjali. 2000. ‘Expression of Inner Power, 17 September 2000’, www.thehindu.com, [accessed 23 November 2018]

Sandro Chia

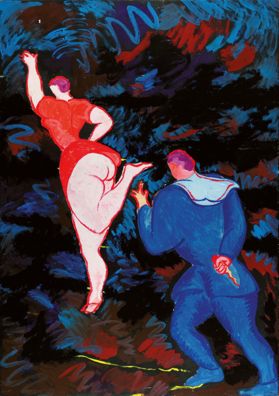

Man Chasing Woman, 1981, Acrylic on paper laid on canvas, 270 x 189.5 cm, Private Collection; © Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photograph courtesy of Sotheby's

I Will Now Allure Her

Commentary by Wei Shieng Chieng

In Man Chasing Woman (1981) Italian artist Sandro Chia explores the oppositional relationships between men and women. The painting shows two protagonists in action—one male and one female. They are depicted against a predominantly black background that is occasionally filled with bold-coloured brushstrokes, suggestive of unseen and unknown mysteries lying beyond.

The voluptuous woman, wearing red (suggesting passion?), has her back towards the viewer. She is running in the direction of the unknown and seemingly away from the man. Her buttocks are in full view—possibly a tease for the man; possibly a result of her frantic rush to get away from him. Her outstretched arm reaches up towards the mysterious distance. The tension between the woman and the man is almost tangible as the man seems to close in on the woman, one hand almost grasping her heel, the other hiding a dagger, seen only by us.

If we make this artwork a lens for reading Hosea 2:5–13, then we may be helped to imagine the woman/Gomer as she continues playing the sensuous whore, cavorting with lovers that give her gifts. The dark background may evoke the ‘hedge’ and ‘wall’ built up against her (Hosea 2:6), and echo Hosea/God’s words, ‘She shall pursue her lovers…she shall seek them but shall not find them’ (v.7).

While Hosea (or the God whom he envoices) imagines Gomer returning to him and saying, ’for it was better with me then than now’ (v.7), we learn that Hosea/God still intends to punish and strip Gomer to shame her in front of her lovers, and makes sure ‘no one shall rescue her out of my hand’ (v.10). When this is read with our eye on the dagger in the man’s hands, we cannot but wonder what ominous ‘better’ end awaits the unknowing Gomer.

References

Perrini, Stefano, 2015. Beyond Transavantgarde: Art in Italy in the 1980s. MA thesis, University of Zurich. pp.35–36

Alison Saar :

Sweet Magnolia, 1993 , Ceiling tin on wood with magnolia leaves

Anita Dube :

Silence (Blood Wedding), 1999 , Human bones covered in red velvet with beading and lace

Sandro Chia :

Man Chasing Woman, 1981 , Acrylic on paper laid on canvas

Finding Gomer, God, and Ourselves

Comparative commentary by Wei Shieng Chieng

Yvonne Sherwood (1996: 21, 42–66) highlights how in Western historical Jewish and Christian receptions of Hosea, Gomer has received various treatments, including as metaphor, fantasy, and dream. The emphasis and sympathies both of Jewish and of Christian traditions often lie with Hosea. For example, the prophet has been imagined on a psychiatrist’s couch, focusing on how to resolve his problematic marriage, while Gomer functions as little more than a bit-player in the prophet’s internal psychological crisis (ibid: 60–61). Or else Hosea is portrayed as the heroic male who redeems Gomer (ibid: 51–52). All this largely ignores Gomer as herself, as a character.

Against this backdrop, Alison Saar’s Sweet Magnolia may help us to appreciate a Gomer whose physicality is made present through her nakedness, even while her personhood seems under threat of being (sub)merged with the land of Israel—just as Saar’s female figure merges with the tree roots. Saar’s oeuvre focuses on women’s bodies to address ideas of race, gender, spirituality, and humanity. Her black African American women figures are often naked and enmeshed in, or emerging from the earth and vines/roots, and take a defiant stance in their poses. Oppressive patterns in Christianity toward women and other subjugated people are largely derived from patriarchal slaveocracies (the social system in which Christianity was born, and which it was only partially successful in transforming). In this context, the female body has frequently been seen as carnal and prone to sin (Ruether 2014: 83, 85). Against this backdrop Saar’s female figure/Gomer’s body could be seen as a female body (a body of colour) resisting, protesting against, and questioning powerful traditions of Western thought and practice.

Sandro Chia’s Man Chasing Woman focuses our sight on the woman’s flesh through a notion of play/tease and coquettishness, and activates for us the action happening in Hosea 2:3, 5–11. The composition reveals the man’s dubious intentions in chasing her, as he wields a dagger, visible only to the viewer. Hence, the act of chasing has little to do with the romantic overtures which the woman may believe she is encouraging. Rather, it points towards imminent danger. Even if the man were chasing her to woo and allure her (in Gomer’s case, the invitation is into the wilderness), it is not an invitation without threat to the woman. Interestingly, while the title Man Chasing Woman suggests the proactive action of the man, the woman is equally proactive in running from him, and perhaps has more dire reasons for doing so. This then opens a space to ask questions, or nurture a certain sympathy for Gomer and her reasons for still preferring and pursuing her ex-lovers.

Anita Dube’s Silence (Blood Wedding) functions like a crystal ball when read with Hosea 2:16–20. It paints a future where the bliss and beauty of a wedding (seen in the bone’s embellishments) will endure, yet it haunts us with the knowledge that amidst this beauty lies silence and possible death. While Hosea and Gomer’s marriage is often read as a victorious story of Hosea’s/God’s unconditional great love and forgiveness towards a whoring Gomer/Israel, Dube’s work hushes that romanticized perspective and reveals there are often two (if not more) conflicting and possibly muted sides of a tale. We may find ourselves recalling that Gomer’s response was scripted by God; words put into her mouth. In this sense, she is a silent presence.

It is in this tradition of how Gomer has been tamed, vilified, or muted, or how the problematic mismatch between a prophet and prostitute is often overshadowed by conventional readings of Gomer and Hosea’s marriage as a godly relationship, marked by love and forgiveness, that these artworks could help us (re)read Hosea 2 ‘against the grain’. Moreover, where the majority of readings take the perspective of ‘Hosea’s marriage’, Sherwood (1996: 255) suggests reading from the inverted angle: ‘Gomer’s marriage’.

In so doing, our attention is brought back to how this is Hosea's as well as Gomer’s marriage, and that it is an exceedingly problematic one. In reading and looking in this way, our consciences may be pricked to approach the characters in biblical narratives not merely as saints or villains, or as belonging only within a Western Christian or Jewish tradition of interpretation. Instead we may find ourselves curious to venture outside, sifting through our assumptions about God, Scripture, tradition, and even the acts of reading and looking themselves. We may be led to a deeper, albeit more layered and complicated, appreciation of not only who God is (or is not), but also how and why our sympathies and condemnations lie with certain characters in Scripture more than others. This in turn may help us rediscover God, Scripture, and ourselves in a different light.

References

Ruether, Rosemary Radford. 2014. ‘Sexism and Misogyny in the Christian Tradition: Liberating Alternatives’, Buddhist-Christian Studies, 34: 83–94

Sherwood, Yvonne. 1996. The Prostitute and the Prophet-Hosea’s Marriage in Literary-Theoretical Perspective (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press)

Commentaries by Wei Shieng Chieng