Psalm 19

The Heavens Are Telling

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Pass at Faido, St Gotthard, 19th century, Watercolour, point of brush, scratching out, over traces of pencil, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; Thaw Collection, 2006.52, Photo: The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

‘All Great Art is Praise’

Commentary by Arnika Groenewald-Schmidt

In his treatise The Laws of Fésole, artist and influential art critic John Ruskin coined the aphorism ‘All great art is praise’ (1877: 351). While for Ruskin all elements of nature, large and small, were a manifestation of God, mountains and clouds held a particular place in his heart and mind. For him the greatest artist was Joseph Mallord William Turner, in whose landscapes and seascapes he saw the sacredness and inexhaustibility of nature better captured than by any other artist (1844: 36).

‘Mountains’, Ruskin wrote, ‘have always possessed the power, first, of exciting religious enthusiasm; secondly, of purifying religious faith’ (1856: 427). Like the vastness of the heavens and the firmament invoked in Psalm 19, the sublimity and aloofness of mountains inspire awe and respect. It is these elements we see captured by Turner in his The Pass at Faido, St Gotthard. Ruskin commissioned the watercolour and later praised it as ‘the greatest work he produced in the last period of his art’.

What made this sheet, and Turner’s work in general, so special to Ruskin was the artist’s ability to communicate a ‘higher truth of mental vision’ that could convey to the viewer ‘the impression which the reality would have produced’ and that would put ‘his heart into the same state in which it would have been’ in front of nature itself (1856: 35–36).

The staggered mountain ranges in the background, the deep gorge accentuating the middle right of the picture, and the boulders formed by the elements in the foreground speak of the force of a nature that is far greater than humankind. Like ‘the heavens’ in Psalm 19, they seem to be ‘telling the glory of God’ (v.1).

The tiny carriage adumbrated to the right and the faint traces of the man-made bridge in the middle ground increase the perception of what human beings are in comparison to the Creator. The artist rendered both the topography and the spirit of the place allowing the beholder to admire and experience this breath-taking scene in its proclamation of the greatness of God’s creation.

References

Nichols, Aidan. 2016. All Great Art is Praise: Art in Religion in John Ruskin (Washington DC: The Catholic University of America Press)

Ruskin, John. 1844. ‘Modern Painters. Volume I. Preface to the Second Edition’, in [1903] Library Edition: The Works of John Ruskin, Vol III, ed. by E.T. Cook, and A. Wedderburn (George Allen: London)

———. 1856. ‘Modern Painters. Volume IV containing Part V Of Mountain Beauty’, in [1904] Library Edition: The Works of John Ruskin, Vol VI, ed. by E.T. Cook, and A. Wedderburn (George Allen: London)

———. 1877. ‘The Elements of Drawing. The Elements of Perspective and The Laws of Fésole’ in [1904] Library Edition: The Works of John Ruskin, Vol XV, ed. by E.T. Cook, and A. Wedderburn (George Allen: London)

Giovanni Costa

Brother Francis and Brother Sun (Frate Francesco e Frate Sole), 1878–85, Oil on canvas, Castle Howard Collection, York; Reproduced by kind permission of the Howard family

‘Like a Bridegroom Leaving his Chamber’

Commentary by Arnika Groenewald-Schmidt

St Francis of Assisi is shown greeting the sun with open arms as it rises behind Mount Subasio in his native Umbria.

Inspired by the Fioretti (‘little flowers’)—tales of the saint’s life written in the Middle Ages—the Italian landscape painter Giovanni (Nino) Costa chose to present the saint at a specific and symbolic time of day. He is in the act of pronouncing his Canticle of the Sun, a praise poem in awe of God’s creation. Like Psalm 19:4–6, the Canticle of the Sun pays special tribute to the sun as the bearer of light and life alluding to the cycle of day and night as well as of birth and death.

Experiencing and rendering this cycle and the beauty of God’s creation lay at the heart of Costa’s work. While not religious in the common sense, the artist believed in the notion of God revealing himself in nature. St Francis to him and many others was the perfect mediator between nature and a spiritual realm and in her comment on this painting nineteenth-century critic Julia Cartwright (1887: 148) concluded that:

it is the presence of Francis which gathers all these separate beauties into one grand and complete whole; it is his song of thanksgiving which lends a deeper meaning alike to the dawn flush which mantles the hilltops, and to the flowers which spring up under his feet.

Costa painted several pure Umbrian landscapes ‘permeated by the Franciscan spirit’ that celebrate the beauty of the place and its spiritual connotations (Agresti 1904: 270). In Brother Francis and Brother Sun, however, he goes further by introducing the friar seen from behind as a point of reference for the viewer and an invitation to step into the landscape to experience and praise its beauty in the same way as the protagonist.

Writing about another of Costa’s Umbrian views of about the same period, his biographer Olivia Rossetti Agresti described how the painter got up every morning at 4 am ‘to seize the precise moment of this effect of light, which lasted only a few minutes’, accounting for the importance of truth to nature for the artist (Agresti 1904: 235–36).

References

Agresti, Olivia Rossetti. 1904. Giovanni Costa: His Life, Work and Times (London: Gay and Bird)

Cartwright, Julia. 1887. ‘The Art of Costa’, Portfolio, 18: 147–151

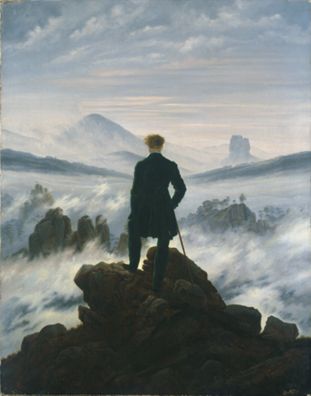

Caspar David Friedrich

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer), c.1817, Oil on canvas, Hamburger Kunsthalle; HK-5161, bpk Bildagentur / Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg / Elke Walford / Art Resource, NY

Contemplating God’s Creation

Commentary by Arnika Groenewald-Schmidt

A man seen from behind contemplates mountain scenery materializing from the receding mist. It is early in the day and the wanderer must have set out before sunrise to reach the elevated viewpoint on top of a mountain. Like him, the viewer is invited to admire this awe-inspiring scene.

This icon of German Romanticism was composed by Caspar David Friedrich from various features of the natural landscape the artist had studied in Saxon Switzerland, an area not far from Dresden, where Friedrich lived for most of his life.

According to specialist Werner Busch (2014: 18) most of Friedrich’s paintings have a spiritual connotation. Protestantism combined with a pantheist outlook on the world have been described as the origins of his religion (Hoch 1990: 71). While in earlier landscapes Friedrich often included a cross to allude to the ubiquity of God, later compositions, like the Wanderer, express it in the evocative, well-balanced sequence of mountain ranges that seem to lose themselves in eternity.

The work helps us picture what it might mean for the ‘words’ of the heavens to reach ‘to the end of the world’ (Psalm 19:4). In a way that resonates with the ideas of German Romantics Ludwig Tieck and Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder—and with Psalm 19:1–4—Friedrich combines elements studied en plein air that he feels elevate the mind. Nature is the language God uses to make himself understood by humanity (Liebenwein-Krämer 1977: 4).

His compositions are structured according to geometric shapes that in their abstractness and perfection have become symbolic of God for many Romantics (Busch 2012: 298). Geometry as well as truth to nature are Friedrich’s tools to express his feelings at the sight of God’s creation, which to him is the principle of art.

As nature shows forth God’s presence, Friedrich sees the artist as a mediator between his creation and humankind, able to convey the essence of the visible world that cannot be expressed in words (Hoch 1987: 60).

References

Busch, Werner. 2012. ‘Schleiermacher als Inspiration für Caspar David Friedrich’, in Religion als Bild—Bild als Religion, ed. by Christoph Dohmen and Christoph Wagner (Schneller & Steiner), pp. 287–304

————. 2014. ‘Friedrich und Dahl: Thematische Verwandtschaften und bildnerische Differenzen’ in Dahl und Friedrich: romantische Landschaften, ed. by Petra Kuhlmann-Hodick et al (Dresden: Sandstein-Verlag), pp. 16–23

Hoch, Karl-Ludwig. 1987. Caspar David Friedrich in Böhmen: Bergsymbolik in der romantischen Malerei (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer)

————. 1990. ‘Zur Ikonographie des Kreuzes bei C. D. Friedrich’, in Caspar David Friedrich: Winterlandschaften, ed. by Kurt Wettengl (Heidelberg: Braus), pp. 71–74

Liebenwein-Krämer, Renate. 1977. Säkularisierung und Sakralisierung. Studien zum Bedeutungswandel christlicher Bildformen in der Kunst des 19. Jahrhunderts (PhD diss. Frankfurt am Main)

Joseph Mallord William Turner :

The Pass at Faido, St Gotthard, 19th century , Watercolour, point of brush, scratching out, over traces of pencil

Giovanni Costa :

Brother Francis and Brother Sun (Frate Francesco e Frate Sole), 1878–85 , Oil on canvas

Caspar David Friedrich :

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer), c.1817 , Oil on canvas

God in Nature

Comparative commentary by Arnika Groenewald-Schmidt

In Psalm 19, the Psalmist (traditionally understood to be King David) expresses his amazement in the face of the infinite expanse of the heavens, and what it says about the Creator. By starting with praise of what we can see and experience in the visible world, David establishes a palpable basis for his reflections on the benefits of meditating on God’s word in Scripture and how it guides human beings to find their way in this world.

The idea of God manifesting himself in nature as a tangible proof of his existence is reiterated throughout the Bible—in Paul’s Letter to the Romans, for instance:

Ever since the creation of the world, his invisible nature, namely, his eternal power and deity, has been clearly perceived in the things that have been made. (1:20)

The interpretation of nature as God’s language, understandable by all humankind, was also prevalent in theories promoted by German Romantics. Indeed, the Psalm’s link between an intense aesthetic experience and ‘the law of the LORD’ (Psalm 19:7–14) seems to chime with the even earlier ideas of Immanuel Kant who equated sublimity with the moral law. Both the aesthetic sublime and the moral law are ‘absolute’ and both awaken human beings to a sense of their highest rational powers (Guyer 2000: §27, 257).

Prepared for by the Enlightenment and further developed during the age of Romanticism, the notion of nature as the revelation of God was an important step towards the rise of landscape painting within the hierarchy of genres at the beginning of the nineteenth century (Liebenwein-Krämer 1977: 9). In some cases landscapes were even elevated to the level of religious art and understood as a new way of engaging the viewer in thoughts about God (Carus 1831: 38).

While none of the paintings chosen for this exhibition is a direct illustration of a passage in the Bible, when considered in light of Psalm 19 each of them may be read as nonverbal praise of God’s awe-inspiring creation, and hence as having a profound affinity with David’s words.

Both Caspar David Friedrich and Giovanni Costa introduce figures viewed from the rear into their landscapes. These figures invite the viewer to witness the breath-taking, symbolic moment when nature awakes at the break of dawn. Costa shows St Francis emphatically reciting his praise poem Canticle of the Sun at the sight of sunrise over Mount Subasio in his native Umbria. Like David in Psalm 19, Francis singled out the sun as the protagonist of the cycle of life. Costa portrays the spreading of light in warm hues typical of Italy.

The cooler tones of a northern sunrise characterize the setting of Friedrich’s worldly wanderer. Arrested by the beauty of the landscape and in awe of the mountains—which to Friedrich were symbols of God—he has been interpreted as contemplating the future, life and death, God and the visual world, and many different aspects that resonate with Friedrich’s claim that a work of art must elevate the mind and preferably trigger religious thought (Hinz 1974: 124).

Mountains and clouds held a particular fascination for both Friedrich and the English writer and artist John Ruskin, especially in relation to their being the purest manifestation of the Creator (Nichols 2016: 377). It is through Ruskin’s words that the spiritual potential of Joseph Mallord William Turner’s art is best revealed. The latter’s The Pass at Faido, St Gotthard portrays a mountainscape formed by the force of nature at the sight of which humanity feels small and powerless. In the spirit of the beginning of Psalm 19, the human being can only stand in awe in face of this spectacle.

Turner, Friedrich, and Costa had all worked from nature in the places portrayed in their paintings, abstracting, combining, and condensing elements according to their personal experience of their respective sites. It is hence through their eyes and their feelings that the viewer is presented with these ‘passages’ from the Book of Nature. They offer us landscapes whose beauty has the power to turn our awe into praise—a praise like the Psalmist’s.

References

Carus, Carl Gustav. 1831. Neun Briefe über Landschaftsmalerei: geschrieben in den Jahren 1815–1824 (Leipzig: Fleischer)

Guyer, Paul (ed.). 2000. Critique of the Power of Judgment, The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant, trans. by Paul Guyer and Eric Matthews (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Hinz, Sigrid (ed.). 1974. Caspar David Friedrich in Briefen und Bekenntnissen (Munich: Rogner & Bernhard)

Liebenwein-Krämer, Renate. 1977. Säkularisierung und Sakralisierung. Studien zum Bedeutungswandel christlicher Bildformen in der Kunst des 19. Jahrhunderts (PhD diss. Frankfurt am Main)

Nichols, Aidan. 2016. All Great Art is Praise: Art in Religion in John Ruskin (Washington DC: The Catholic University of America Press)

Commentaries by Arnika Groenewald-Schmidt