Isaiah 6

Holy, Holy, Holy

Giotto

Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata, Before 1337, Fresco, 270 x 230 cm, Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe; Universal Images Group North America LLC / DeAgostini / Alamy Stock Photo

The Theatre of Divine Life

Commentary by Matthew A. Rothaus Moser

The Legend of Francis is a series of twenty-eight frescoes in the Upper Church of the Basilica of Saint Francis at Assisi, painted by Giotto and his workshop. They follow the official chronicle of the Life of Francis by St Bonaventure.

In the scene showing Francis’s stigmatization, Giotto’s depiction of the seraph seems to recall elements of the vision of Isaiah 6—particularly its six wings. But (as in Bonaventure’s account) the seraph here is the crucified Christ, and Christ is also the ‘burning coal’ who sanctifies Francis by marking him with his own wounds.

With a naturalism that would be much imitated, Giotto sets the life of the saint within recognizable and habitable spaces, a ‘theatre of life’ (Lunghi 1996: 65). This ‘everydayness’ in Giotto’s frescoes might seem quite different from Isaiah’s vision of the celestial throne of God. Isaiah 6 is set in the Temple while Giotto’s settings are remarkable in their familiar, earthly specificity. Yet Giotto’s approach may help us see that Isaiah’s own attention to God’s presence is not, in fact, a stepping outside of ordinary history. Yes, the seraphim of Isaiah 6 proclaim that the Lord’s glory fills the Temple, but it also spills ever outward, filling the whole world (v.3). God’s glory may be encountered anywhere. It can break into ‘theatres of life’ of all kinds and in all periods; today where you are, just as in medieval Italy.

Francis’s dynamic posture communicates something of the shock to the human creature of this divine in-breaking. He is in mid-motion, having dropped down onto his right knee. His upper body angles itself toward the seraph as it bursts onto the scene. Along with his curled fingers and his facial expression, this allows Giotto to distill in a single image the drama of his surprise. The fresco may offer us a theatre of life, but it is certainly still theatre—no less dramatic for the everydayness of its setting.

The presence of Francis’s halo, despite being a supernatural element, is integrated into Giotto’s naturalistic depiction without any sense of awkwardness or inappropriateness. Like the three ‘holies’ that ring out in Isaiah’s theophany, this halo shows God’s sanctity is manifest ‘on earth as in heaven’. It occurs within the scheme and movements of the natural order, as human and divine life are enfolded together in holy history.

References

Lunghi, Elvio. 1996. The Basilica of St Francis in Assisi (New York: Roadside Book Company)

James Hampton

The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations' Millennium General Assembly, c.1950–64, Mixed media, Smithsonian American Art Museum; Gift of anonymous donors, 1970.353.1-.116, © James Hampton (orphaned work); Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC / Art Resource, NY

Found Glory

Commentary by Matthew A. Rothaus Moser

Over the course of fourteen years, James Hampton slowly and privately constructed what would prove to be his only major artistic work: The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations' Millennium General Assembly. Hampton handcrafted The Throne from ‘found objects’: cardboard, plastic, discarded furniture, jelly jars and light bulbs, metallic foils, and purple paper (now faded to a light brown).

What might Hampton’s use of reclaimed and recycled ‘everyday’ objects help us see about Isaiah’s vision? How might ‘found art’ disclose a ‘found theology’: a theology of how the presence and glory of God is discovered in unfolding historical encounters (Quash 2013: xiv)? Much like the prophet Isaiah himself, these found objects, painfully ordinary, are taken up into a higher purpose, re-dressed, transformed, put to new work. The artist’s imagination and vision become like the seraph’s coal, both purifying and transforming the meaning and purpose of their objects.

The richness of Hampton’s vision lies precisely in the humility of its components; its humility is the source of its magnificence. Those who stand before it experience the glory of a God who humbles the proud and elevates and glorifies the humble. The collective components of The Throne, reworked by the artist, overwhelm the space in the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery, much like the robe of the LORD that fills the Temple in Isaiah’s vision (6:1).

Indeed, when The Throne was first discovered in that Washington DC garage, its glory exceeded the space, spilling out of its containment onto the sidewalk and the street, reminding us of Isaiah’s encounter with the glory of God which fills the entire earth (6:3).

The glory of God is ready to burst forth, finding and transforming ordinary people and common things. Hampton’s transforming vision raises the found to higher significance, similar to the way that Isaiah’s speech is not his own, but becomes a vessel for YHWH's voice. The found objects and the found prophet each offer up their own humble ‘Here I am—send me’.

References

Quash, Ben. 2013. Found Theology: History, Imagination, and the Holy Spirit (London: Bloomsbury)

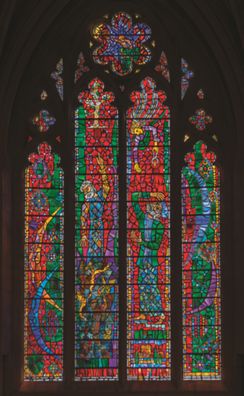

Rowan LeCompte

Isaiah Clerestory Window, 2014, Stained glass, 7.2 x 3.2 m, Washington National Cathedral; S8 Window, Photo: Danielle Thomas, Courtesy of the Washington National Cathedral

‘Here I am’

Commentary by Matthew A. Rothaus Moser

The centrepiece of Isaiah 6 is a question and an answer. God asks, ‘Whom shall I send?’ and Isaiah answers with a phrase that comes up repeatedly in the biblical story, harking back to the words of Abraham, of Jacob, and of Samuel: ‘Here I am’ (hineni) (v.8).

This phrase captures a particular spiritual attitude of availability and receptivity to the command of God, countering the attitude of Adam and Eve who hid from God’s presence. How does one capture the spiritual attitude expressed in this phrase—what the French spiritual masters called disponibilité—in visual form?

Rowan LeCompte’s depiction of Isaiah represents the attitude well. His image of the prophet in the right-hand of the two central lancets of this stained-glass window is strange and unsettling. Isaiah’s diagonal ascent of some gentle steps is interrupted by a far starker vertical summons as the cherub descends with its burning coal. Isaiah’s response is to fling his head dramatically backwards. This is a man in the process of realigning himself; opening himself to being reconfigured.

The thin verticality of LeCompte’s Isaiah, as well as of the window itself, and its location on the clerestory level of the cathedral, has an anagogical (upward-moving) effect, reminding us that the self-offering attitude of ‘Here I am’ involves a willingness to be drawn upward, expanded, unmade, and remade, by the voice of the Lord. Isaiah’s elongated body, stretched beyond normal human proportions, serves as an image of what the prophet must undergo if he is to speak the words of the Lord to Israel in the crisis of its judgement and exile. Not only his words, but his very being, will have to be stretched.

But we may not forget that prior to Isaiah saying ‘Here I am’, he first said, ‘Woe is me!’ (v.5). LeCompte manages to represent not only Isaiah’s disponibilité but also his fear and trembling at the vision of God in the way he poses Isaiah’s arms and hands. One hand seems self-protectively raised above his head to shield himself from the brilliance of God’s glory, even as the other is inquisitively and receptively open to both the seraph and his vocation.

Isaiah’s self-offering is inseparable from his humble realization that he is a ‘man of unclean lips’ (v.5) in need of purification from the seraph’s burning coal.

Giotto :

Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata, Before 1337 , Fresco

James Hampton :

The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations' Millennium General Assembly, c.1950–64 , Mixed media

Rowan LeCompte :

Isaiah Clerestory Window, 2014 , Stained glass

The Healing Wounds of the Glory of God

Comparative commentary by Matthew A. Rothaus Moser

The seraphim above God’s throne proclaim what is known in the Christian liturgy as the trisagion: 'holy, holy, holy'. The holiness of God is the glory of divine love that fills the cosmos. The glory of divine love in Isaiah 6 holds together judgement with the hope for restoration and transformation. Each of the works of art in this exhibition illumines Isaiah’s picture of heavenly glory, judgement, and salvation.

James Hampton’s use of shimmering tins and foils and purple paper give his Throne the radiance of divine kingship. When light catches the foil of Hampton’s work, it refracts outward in all directions, much like the seraphic proclamation of God’s glory throughout the entire earth.

Rowan LeCompte’s Isaiah Window makes use of light too, though diffusing it, creating a visible harmony of colours and shades.

Giotto shows the divine glory mediated by a seraph, as the text of Isaiah does, but he makes this mediation christological. It is a crucified glory that wounds St Francis, marking him forever as an image of the overflowing excess of Christ’s love.

The wounding quality of Giotto’s seraphic glory can serve to remind us that Isaiah’s prophetic calling is one of judgement rather than of immediate consolation. Yet the fruitful tension in Isaiah 6:9–13 is that the judgement of God contains within it the promise of redemption—even if it is not readily apparent in the judgement itself. God will judge and punish; but God will also atone and redeem. The two restored chapels that frame the figure of Francis in Giotto’s image recall God’s commissioning of Francis: ‘My house lies in ruins; restore it’ (Bonaventure The Life of St. Francis, 2.1). The first phrase is judgement, the second the hope of restoration.

Divine judgement needs illumination. Israel’s exile is a calamity, a searing trauma in the biblical imagination. What message could be discerned in Israel’s imprisonment in Babylon? Without prophetic illumination, God’s judgement is opaque, inscrutable, even foreboding. The meaning of God’s judgement is like LeCompte’s stained-glass window at night when no light shows through. No matter how intensely we examine the lancets, we can discern in them no sense, no order. Yet when lit by the sun, the glass comes alive with the hope of meaning and purpose.

Similarly, the prophet’s words of judgement bear within them a word of hope by the simple fact that God continues to speak to Israel. God is not silent; his judgement is not final, his punishment not opaque. The word from the throne is a covenantal judgement, wounding in order to heal. Hampton captures this tension perfectly by placing a placard high above The Throne. It is the apex of both his art and his theology: ‘Fear not’.

The wounding transformation begins with Isaiah himself. Who must Isaiah become in order to perform his divine vocation? He undergoes his own judgement and atonement (‘Woe is me for I am a man of unclean lips!’; v.5) so that his identity can be transformed into that of a prophet who can perform his commission. The liturgical setting of the LeCompte window, like the setting of Isaiah’s vision in the Temple, befits this narrative of purgation, transformation, and mission. In the liturgical movement of the cathedral, one passes the Isaiah window on the way toward the eucharistic altar, there humbly to receive atonement and transformation. One passes the window again at the benediction, when one is sent out into the world in peace.

Just as Isaiah was transformed by his encounter with the seraph, so too was St Francis. When he received the stigmata, Francis’s flesh became a seraphic performance of Christ’s incarnate life. St Bonaventure relates a story of how Francis, burning with the fire of Christ’s charity as he travelled, touched the body of a companion who was shivering with cold. The touch of Francis’s holy flesh warmed the shivering man because Francis himself had become the seraph’s burning coal (v.6) that purifies, illumines, and enflames with the fires of love. Francis performs both the reality of Christ and the seraph. Like Isaiah, he beholds the glory of God, suffers transformation, and receives the vocation to go into the world, singing the seraphic trisagion amidst the choruses of Babylon.

References

Bonaventure. The Life of St Francis. 1978. Trans by Ewert Cousins, in The Soul’s Journey into God, The Tree of Life, The Life of St Francis, The Classics of Western Spirituality (New York: Paulist Press)

Commentaries by Matthew A. Rothaus Moser