2 Maccabees 7

The Holy Maccabean Martyrs

Antonio Ciseri

The Martyrdom of the Seven Maccabees, 1857–63, Oil on Canvas, 450 x 260 cm, Church of Santa Felicita, Florence; akg-images / Rabatti & Domingie

Suffering as High Poetry

Commentary by Nerida Newbigin

The biblical text is a starting point, providing the characters (Antiochus, the widowed mother and her seven sons, and the executioners) and the location (Jerusalem, according to Gregory of Nazianzus [Vinson 2003: 72–84], though here looking like the Rome of Santa Felicita). It does not seem to provide spiritual inspiration to a higher good; rather it is taken as high poetry, which the painting attempts to rival.

The gruesome torments of the sons are not shown. Their bodies are not grotesquely mutilated, but rather they are exquisitely represented in contorted lifeless poses, their unblemished flesh half covered with rich cloths. Their pain is not visible, but the tragedy of their lost lives is.

All the focus is on the mother. Her sons are in front of her. Her last born is naked on her lap, but she raises her arms serenely, even triumphantly, to heaven, offering them all to God who has promised eternal life.

The altar where they had been ordered to make their sacrifice to the pagan gods, together with the pig’s head that they had been ordered to eat, are visible in the background between her arms, but she reaches beyond them in silent faith that God’s covenant will be kept. The tyrant in the background, despite his arrogant pose, is reduced, like the executioners, to irrelevance.

Antonio Ciseri (1821–91) had begun working on his masterpiece as early as 1852, but it was only formally ‘commissioned’ by Santa Felicita in 1861, after Ciseri had offered his work to the nuns for the cost of materials only. Where Gregory focused on the triumph of reason over emotion, Ciseri’s scene embodies romantic pathos wherever the eye turns, and works on and through the emotions. His motives may well have been personal artistic ambition as much as spiritual devotion.

References

Del Bravo, Carlo. 1975. ‘Milleottocentosessanta’, Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa: Classe di Lettere e Filosofia , serie 3, 5.2: 779–95

François, Maria Cristina. 2011. ‘Dall’Archivio di Santa Felicita: cronistoria del Martirio dei Maccabei di Antonio Ciseri, “onore di Firenze e d’Italia”’, Amici del Palazzo Pitti: Bollettino, pp.35–46

Gargani, Gargano. 1863. Del quadro in tela: i Maccabei e la madre, pittura del professore Antonio Ciseri da Locarno. Discorso (Florence: Le Monnier)

Vinson, Martha (trans.). 2003. ‘Oration 15: In Praise of the Maccabees’, in St Gregory of Nazianzus: Select Orations, Fathers of the Church (Bloomington: Indiana University Press), pp. 72–84

Neri di Bicci

Saint Felicity and Her Seven Martyred Sons, 1466, Tempera on panel, gold leaf ? (TBC), Church of Santa Felicita, Florence; Sailko / Wikipedia / CC BY 3.0

Maccabean Saints

Commentary by Nerida Newbigin

In Florence, the mother of the Maccabees becomes Santa Felicita, taking the name of a Roman saint, likewise martyred with her seven sons. The church of Santa Felicita and its convent of Benedictine nuns, located at the southern end of the Ponte Vecchio and thus outside the original city walls, was probably dedicated in its earliest times to the Holy Maccabees. Certainly, their feast day, 1 August, was its principal feast day.

In 1466, Neri di Bicci was commissioned to paint this altarpiece and predella to make a visual representation that would fuse the two traditions—of the Holy Maccabees and of Santa Felicita and her seven sons—in a single work. The biblical narrative of 2 Maccabees 7 was taken into a new reality.

In the main panel above, the mother, delicately haloed and bearing the palm of martyrdom and a book, has become Santa Felicita. On either side are her sons, their bodies restored to perfection in heaven. Each has a number. The names and numbers are then inscribed below—Quirilius, Emenarder, Petrus, Secondinus, Rafianus, Aquila, Domitianus. These names were a new accretion to the story, and belonged in fact to other saints commemorated on 1 August, listed immediately after the Maccabees in the influential Martyrology attributed to St Jerome (c.342/47–420 CE). The same names are found in a play entitled Saint Felicity the Jew and Her Seven Martyred Sons, printed around 1490 but possibly contemporary with the panel, whose script welds together the sainted mother, the Maccabean sons, and their rhetorical justifications of their stand.

Nothing in the visual arts can represent the words of the sons; their defiant eloquence as they refuse to submit to the threats and blandishments of the king who offers them life in this world if they break their commitment to the Law. The predella panel below shows a sequence of physical torments, to be read from left to right, from the oldest son to the youngest.

The central scene of the predella shows the mother and her seven sons, with Eleazar on the right hand of Antiochus, and the executioners on the left. Their distinctive gestures remind us that the danse macabre was originally the chorea machabaeorum or ‘dance of the Maccabees’. The pagan tormentors have been literally de-faced in a damnatio memoriae.

References

Balocchi, Giuseppe. 1828. Illustrazione dell’I[llustre] e R[eale] Chiesa Parrocchiale di S. Felicita che può servire di Guida all’osservatore (Florence: Pagani), pp. 49–50, 135–38

Granger Ryan, William (trans.). 2012. Jacobus de Voragine. The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 1: 364–65 (The Seven Brothers, Sons of Saint Felicity), 2:33 (The Holy Maccabees)

Macabre, n.1, www.oed.com [accessed 27 February 2023]

La festa di sancta Felicita hebrea quando fu martyrizata con septe figluoli. Before 1495. [Florence: Bartolomeo de’ Libri], available at https://data.cerl.org/istc/if00059200

Unknown Byzantine artist

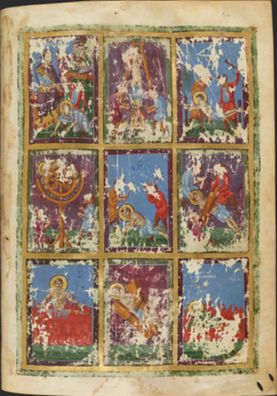

Illustration to Gregory of Nazianzus, Homily 15: In Praise of the Maccabees, 879–83, Illuminated manuscript, 435 x 300 mm, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris; Grec 510, fol. 340r, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Reason over Emotion

Commentary by Nerida Newbigin

This page illustrating the martyrdom of the Maccabees comes from the first surviving illustrated book produced for a Byzantine emperor. It is a ninth-century manuscript of Gregory of Nazianzus’s Homily 15, ‘In Praise of the Maccabees’, which was delivered in 362 CE. Gregory was responding to an attempt to separate Christianity from its Hellenic and Jewish roots by introducing the cult of the Maccabean martyrs into the Christian calendar (Vinson 2003: 15).

The nine panels of this introductory folio show: first, Eleazar the priest being cast to the ground before the Emperor Antiochus as the brothers look on, then the martyrdom of the seven brothers, and finally that of the mother—here called Solomonia—who leaps into the fire. Only two of the individual brothers can be identified by their torments; it is the accumulation of torture, not the individual torments, that matters.

The emperor’s rhetoric of cruelty is a total failure: he cannot persuade those who are divinely inspired, and divine inspiration makes them ever more articulate in their refusal to eat meat. The panels do not directly illustrate the torments described in Gregory’s enormously influential homily, which brings together the narratives of 2 Maccabees and 4 Maccabees. Rather, it organizes and rationalizes the narrative in a series of simple frames. As Gregory argues, the story of the martyrs is the story of the triumph of reason over passion.

Passions, however, cannot be suppressed in the reader. The page is worn from more than eleven centuries of handling, as the homily was read as part of the liturgy on the feast day of the Maccabees: 1 August. But in addition, the faces of the tormentors have been systematically scraped away, to deny them all recognition alongside the widow’s sons.

References

Brubaker, Leslie. 1999. Vision and Meaning in Ninth-Century Byzantium: Image as Exegesis in the Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus (Cambridge: CUP), pp. 417–20

______. 2017. ‘The Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus’, in A Companion to Byzantine Illustrated Manuscripts, ed. by Vasiliki Tsamakda (Leiden: Brill), pp. 351–65

Vinson, Martha. 1994. ‘Gregory Nazianzen’s Homily 15 and the Genesis of the Christian Cult of the Maccabean Martyrs’, Byzantion, 6: 166–92

______ (trans.). 2003. ‘Oration 15: In Praise of the Maccabees’, in St Gregory of Nazianzus: Select Orations, Fathers of the Church (Bloomington: Indiana University Press), pp. 72–84

Antonio Ciseri :

The Martyrdom of the Seven Maccabees, 1857–63 , Oil on Canvas

Neri di Bicci :

Saint Felicity and Her Seven Martyred Sons, 1466 , Tempera on panel, gold leaf ? (TBC)

Unknown Byzantine artist :

Illustration to Gregory of Nazianzus, Homily 15: In Praise of the Maccabees, 879–83 , Illuminated manuscript

Holy Maccabees, Jewish Saints

Comparative commentary by Nerida Newbigin

Even though the Maccabean martyrs cannot officially be saints because they died before Christ was born, they have been regarded as worthy of emulation for their unswerving devotion to the ways of their fathers. The three images in this exhibition show a process of cultural appropriation as the Holy Maccabees are incorporated into the Christian tradition and become saint-like.

The story of the Hebrew widow and her seven sons, who choose martyrdom at the hands of Emperor Antiochus rather than breach their covenant with God by eating pork, comes from 2 Maccabees. It is retold, in an emotionally embellished version, in 4 Maccabees. Jerome included 2 Maccabees among the deuterocanonical works ‘for the edification of the people’, while 4 Maccabees had little presence in the Western Church (though it is now available in the NRSV).

The widow and her sons have served as archetypes in various ways. The widow who willingly sacrifices her sons in this world to preserve them for eternal life in the next is the archetype for all mothers in times of war, and (like Mary) she offers up her offspring for a higher good. The brutality of their martyrdom is the catalyst for political uprising in the Maccabean Revolt and the cleansing of the Temple in Jerusalem. From the earliest Christian commentators, the widow and her sons were seen as archetypes of the Christian martyrs, born through death into eternal life. The sons, moreover, are behavioural models for children, adolescents, and young men: they obey the Law, and they exercise rational thought and eloquent argument in defiance of their emotions—above all fear of pain. Like Daniel, and like the three youths in the fiery furnace, the Maccabean Martyrs were examples of youthful faith and virtue.

The text of 2 Maccabees 7 presents in detail the reasoned response of the martyrs to the king’s order to eat meat. They reply ‘in their own tongue’ (v.8; see also vv.21, 27), and articulate their acceptance of death in the hope of eternal life. The text thus operates in three rhetorical ‘languages’: the visual spectacle of horror as a means of persuasion; the words of Antiochus, speaking in his language; and the words of the mother and her sons, in the language they share with God and with Moses.

The visual commentary offered here goes well beyond the text provided by 2 Maccabees 7, largely because that text itself entered immediately into a process of rewriting, re-interpreting, embellishment, and repurposing. The purpose of the images discussed here is to represent the Seven Maccabees, in as much narrative detail as possible, to fit a series of contexts.

The Maccabean martyrs were contested territory. In the fourth century, Gregory of Nazianzus made a counterclaim to the Jewish tradition that cast them as a collective symbol of Judaism itself, and accorded them the veneration traditionally awarded to Christian martyrs. In his commentary, they embody the triumph of reason over emotion (Vinson 2003: 72–84). The nine-panel illustration that precedes his homily embodies his thesis: it is a statement, enumeration, and conclusion of the story, focusing on its rational symmetry, and not on the emotive detail of each torment.

In fifteenth-century Florence, the nuns of Santa Felicita, who honoured their patron St Felicita on the feast day of the Maccabean Martyrs, commissioned an altarpiece that would consolidate the two into one, attributing to the Jewish martyrs all the qualities and powers of a Christian saint.

In the nineteenth century, at the height of Romanticism and growing Italian nationalism, Antonio Ciseri’s altarpiece of the Holy Maccabees, also in Santa Felicita, returns the martyrs to their pre-Christian origins. The focus is on the suffering mother, while the holiness of her steadfast sons is represented by the beauty of their dead bodies.

References

Vinson, Martha (trans.). 2003. ‘Oration 15: In Praise of the Maccabees’, in St Gregory of Nazianzus: Select Orations, Fathers of the Church (Bloomington: Indiana University Press), pp. 72–84

Commentaries by Nerida Newbigin