Galatians 2:15–21

I Live By Faith

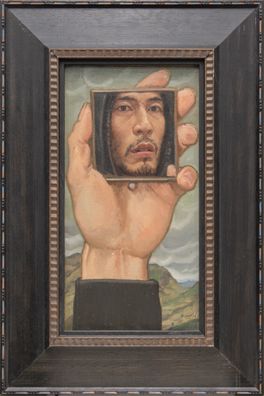

Yong You

Self-Portrait with Mirror in Hand, 2017, Oil on wood, 40 x 20 cm; ©️ Yong You; Photo courtesy The Nagel Institute for the Study of World Christianity

Self-Portrait as Christ

Commentary by Victoria Emily Jones

In this self-portrait by Chinese Christian artist Yong You, a hand with a puncture wound holds up a small square mirror that reveals the artist’s hood-framed visage, while the mountains of Zhejiang Province lie in the background. The stigma, centrally placed, identifies the artist with Christ. Thus the portrait subject is at once Yong You and the Christ with whom he has been crucified, whose spirit lives in him (Galatians 2:19–20), and whose likeness he is being conformed to (Romans 8:29; 2 Corinthians 3:18). ‘Self-Portrait alludes to the fact that my life is in Jesus’ hand’, Yong You says (2019: 82)—acknowledging that the figure is not only himself, as the title states, but also the Divine. Through Christ’s reconciling act, the two are united.

There is art historical precedent for this merging of one’s personal identity with Christ’s, most famously in Albrecht Dürer’s Self-Portrait of 1500. While some interpret Dürer’s portrayal of himself in the guise of Christ as hubristic, others see it as affirming the doctrine of the imago Dei (which states that all humans were created in God’s image), and the ethical injunction known as imitatio Christi, whereby Christians are called to imitate the example of Jesus; to reflect him in their daily lives (1 John 2:6; Ephesians 5:1–2; Philippians 2:5; John 13:34).

Both ideas seem to be at play in Yong You’s image, which additionally alludes, by means of the nail mark, to the Crucifixion and its substitutionary aspect. Yong You looks in the mirror and sees Christ because Christ’s death and resurrection have made him a partaker of the promise (Ephesians 3:6), of glory (1 Peter 5:1), and of the divine nature (2 Peter 1:4).

The nail mark may also refer to the persecution suffered by Christians in China and elsewhere. Paul himself was physically assaulted for his beliefs on more than one occasion; as he says later in his letter to the Galatians, ‘I carry the marks [stigmata] of Jesus branded on my body’ (6:17).

References

2019. Matter + Spirit: A Chinese/American Exhibition (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Calvin University): 21, 82–83

Roger Kemp

Ascension, c.1960, Synthetic polymer paint on composition board, 119.8 x 181.2 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of the National Gallery Society of Victoria, Governor, 1983, A40-1983, ©️ Roger Kemp Estate

Winging Crosses

Commentary by Victoria Emily Jones

Born in 1908 in the mining township of Eaglehawk in Victoria, Australia, but moving to Melbourne at age 5, Roger Kemp was raised in a devout Primitive Methodist family. As an adult he did not participate much in organized religion, but he had transcendental leanings and was interested in the spiritual in art. His encounters with Christian Science and theosophy in the late 1930s bore a lasting influence on his paintings (Heathcote 2007: 50–52).

Two of the recurrent motifs in Kemp’s work are crosses (sometimes with human torsos attached) and winged forms. They are often combined, as here. Both have a balletic quality. Stemming from the many religious cults that equate birds with the soul, these forms were Kemp’s symbol for humanity soaring upward to enlightenment (ibid 106 n.217; 181).

While art historian Christopher Heathcote emphatically states that Kemp’s ‘cruciforms’ do not signify the Crucifixion or any orthodox theological principle (ibid 7, 111), Kemp must have been relying on at least some of the associations conjured by that millennia-old Christian symbol, such as ego-death, spiritual life/immortality, and cosmic order. He was not opposed to his work being read through a Christian lens: from 1954 to 1968 he entered the Blake Prize for Religious Art annually, and participated in several church exhibitions in the mid-1960s.

Whatever its maker’s intentions, compelling interpretative possibilities are opened up when Kemp’s Ascension is ‘read’ alongside Galatians 2:19–20:

I have been crucified with Christ. It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself up for me. (Galatians 2:20)

Christ in the centre of the painting is surrounded by other crucified, haloed figures who are taken up into a grand choreography of spirit. Embodying Paul’s death–life paradox, they spread their arms in a posture that simultaneously evokes both a being pinned to a crossbeam and a being poised in flight.

Jews and Gentiles alike, Paul says, are made righteous by their faith in Christ’s work of redemption on the cross, not by their own performance (Galatians 2:16). This unearned righteousness gives wings, sets free. Christ opened up a way to God that we enter not through rule-keeping or moral effort but through Christ himself, slain and risen.

References

Crumlin, Rosemary. 1988. Images of Religion in Australian Art (Kensington, NSW: Bay Books)

Heathcote, Christopher. 2007. A Quest for Enlightenment: The Art of Roger Kemp (Melbourne: Macmillan)

Julia Stankova

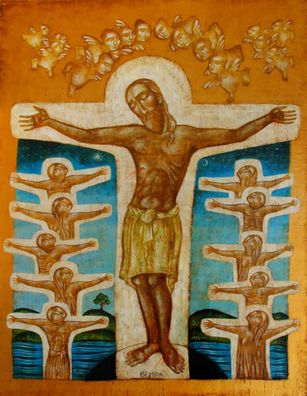

The Crucifixion, 2004, Tempera, gouache, watercolour, and lacquer on panel, 60 x 45 cm, Collection of the artist; ©️ Julia Stankova, photo courtesy of Julia Stankova

A Cruciform Life

Commentary by Victoria Emily Jones

Julia Stankova is a Bulgarian artist indebted to and innovating on the Orthodox iconographical tradition that emerged in the Balkans in the Middle Ages. Her 2004 Crucifixion is, like all Crucifixion icons, an image of both death and life. It portrays Christ hanging on the cross—but this instrument of execution exudes light and nimbs his head and penetrates a dark semicircle at the base that likely represents the abyss, the underworld. Christ’s love plunges into the depths. Above him hovers a host of angels, and behind him night turns to day.

To Christ’s sides on a smaller scale, ten half-length figures—men and women—mirror his pose of outstretched arms, each surrounded by the same bright cruciform outline. They all look up to him, ‘the pioneer and perfecter of [their] faith’ (Hebrews 12:2). These are those who, like the apostle Paul, have been justified by Christ—crucified with him and now sharing in his life (Galatians 2:20). That life is marked by a cross-shaped ethic of sacrificial love and incarnational presence.

In the background is a paradisal landscape with a flowing river; green, flower-studded hills; and a lush tree with an apple hanging from it, alluding to the forbidden fruit of Eden. According to Christian tradition, it was Adam and Eve’s taking of this fruit that brought sin into the world. Deliverance was wrought by another tree—the tree of the cross, whose fruit is Christ. The red of the distant apple is echoed in the blood that spurts from Christ’s five wounds. This blood, Christians believe, restores humanity to a right relationship with God and to a renewed Eden.

Those who put their faith in the efficacy of Christ’s perfect sacrifice, rejecting all attempts at self-justification (which will always only ever fall short), enjoy the benefits that are Christ’s. The ranks of light-surrounded followers that flank Stankova’s Christ have relinquished any sense of self-entitlement, instead resting fully in Christ’s light-exuding, finished work.

Yong You :

Self-Portrait with Mirror in Hand, 2017 , Oil on wood

Roger Kemp :

Ascension, c.1960 , Synthetic polymer paint on composition board

Julia Stankova :

The Crucifixion, 2004 , Tempera, gouache, watercolour, and lacquer on panel

Crucified with Christ, Risen in Him

Comparative commentary by Victoria Emily Jones

Union with Christ is a major theme for the Apostle Paul. His epistles (not to mention the New Testament as a whole) are full of the language of being ‘in’ Christ and Christ being ‘in’ believers—a double habitation. More specifically, Paul describes in several places, including our present passage, how believers’ old selves, in a mystical sense, have died with Christ, and how their new selves have risen with him (see Romans 6:3–14; Colossians 2:11–12, 20; 3:3) and now live in him.

This ‘death’ of the believer is, in part, death to the Law’s power to condemn. Paul was writing to the Galatian church to counter the false teaching that Gentile converts must keep the Jewish Law (in particular, the rite of circumcision) in order to be accepted by God. The true gospel, Paul writes, is that we are justified not by our acts of obedience but by faith in Christ alone—in his obedience, enacted perfectly on our behalf. Paul interprets Jesus’s meritorious life and death as a once-and-for-all fulfilment of the Law’s demands on sinful humanity, such that we are spared the punishment our rebellion deserves. If we are one with Christ—which is the invitation of Christianity—our fallenness has been nailed to the cross, and we are reborn of Christ’s Spirit.

‘Liv[ing] to God … by faith in the Son of God’ (Galatians 2:19–20) entails trusting in the all-sufficiency of Christ as well as assuming the posture of humility, self-giving, and surrender to the divine will that he modelled—living a cruciform life. Julia Stankova visualizes this posture in one of her Crucifixion paintings, in which ten Christ-followers extend their arms in imitation of their exemplar, on whom they set their eyes. Their identities are married to Christ’s. His life flows through theirs, and his holiness—signified by the halo around his head that merges with the cross and becomes a full-body outline—is accorded to them.

Yong You’s Self-Portrait with Mirror in Hand is a more personal take on this passage and its parallels. It is an identity statement—Yong You’s claim of oneness with the crucified and risen Christ. The face in the mirror is Yong You’s, but the hand that holds it has a hole through the palm, one of Jesus’s distinguishing features, which suggests the two men’s mutual indwelling. Through this painting, and like Paul, Yong You confesses the power of the cross in his own life—a power that imputes Christ’s righteousness to him, justifying him before God, and that equips him to live the Christ-life, characterized by love.

Death that brings forth life is the central, vitalizing image of Galatians 2. Roger Kemp explores this idea in more universalized terms (that is, without the theological particularities of Paul) in his Ascension. This semi-abstract painting merges human and flying forms: individuals in cruciform postures flocking with what appear to be birds or airplanes, the two barely distinct from one another. The Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo, which toured Australia in 1936–37, was influential in his development of these motifs (Heathcote 2007: 44), dancelike as they are. Circles—traditionally a symbol of wholeness or eternity—also fill the composition. ‘For Roger Kemp, art was inseparable from metaphysics’ (ibid 108), and in 1955 he cryptically described his aim as ‘to express the substance within world rhythm’ (ibid 181). Stretched out in death and yet soaring and alive, the figures, Kemp might have said, have died to their baser selves and attained a higher consciousness. Paul would perhaps see in Kemp’s painting Christ giving himself in love to a broken world and calling that world to enter into his death so that it might experience true, Spirit-empowered life.

References

Heathcote, Christopher. 2007. A Quest for Enlightenment: The Art of Roger Kemp (Melbourne: Macmillan)

Commentaries by Victoria Emily Jones