Psalm 121

I Will Lift Up My Eyes

Frederic Edwin Church

Pichincha, 1867, Oil on canvas, 78.7 x 122.4 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art; 125th Anniversary Acquisition. Gift of the McNeil Americana Collection, 2004, 2004-115-2, Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art

Vitality and Power

Commentary by Amanda M. Burritt

In Pichincha, American artist Frederic Edwin Church reflects visually on the rich and diverse interconnected web of creation. Church’s beliefs and art were influenced by the writings of the German scientist Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), who believed in a divine teleological imperative embodied in the natural physical world. Humboldt understood nature to be unity in diversity, ‘one great whole animated by the breath of life’ (Gould 1989: 97).

Church sketched Pichincha in Ecuador in 1857 but the painting was completed in his studio in 1867. In 1859, Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published. Darwin’s interpretation of the natural world, in which species existed in a random competition for survival and development, challenged Church’s worldview. Nevertheless, he remained entranced by the awesome beauty, diversity, and complexity of nature.

Echoing Humboldt, Church believed a landscape painting did not need to be a literal rendition of a scene in every detail. Rather, it could be an intriguing capriccio in which disparate elements existed in apparent harmony. Pichincha is a composite of different Ecuadorian landscapes, in which palm trees that cannot grow on the Andean high plains nevertheless do so. Church’s displaced trees even bear fruit, evocative of nature’s creativity and abundance despite their unnatural location.

The foreground of Pichincha depicts a deep, dark valley. Transcending the darkness and encompassing the whole composition is a dispersed light which emanates from the central sun. There is a divine protective and life-giving presence over the mountains. The constancy of the rising and setting of the sun is a powerful symbol in a location so close to the equator.

Church’s volcano is dormant, but that same volcanic mountain can be an active fearsome force of nature. Tiny people and a donkey cross the chasm on a flimsy-looking bridge suspended between two ridges. This act of faith evokes the traveller’s situation in Psalm 121. Danger is all around but there is also the protective presence of the Creator, manifested in light and in the richness of creation.

He will not let your foot be moved; he who keeps you will not slumber. (v.3 NRSV)

References

Gould, Stephen Jay. 1989. ‘Church, Humboldt, and Darwin: The tension and harmony of art and science’, in Frederic Edwin Church, ed. by Franklin Kelly (National Gallery of Art: Washington DC), pp.94–107

Huntington, David. 1963–64. ‘Landscape and Diaries: The South American Trips of F.E. Church’, The Brooklyn Museum Annual, 5:65–98

Miller, Angela and Chris McAuliffe. 2013. America: Painting a Nation (Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales)

Unknown artist

Mosaic of the Good Shepherd and decorated vault, Early 5th century, Mosaic, Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna; Alfredo Dagli Orti / Art Resource, NY

Shepherd and Ruler of All

Commentary by Amanda M. Burritt

The Lord will keep your going out and your coming in

from this time forth and for evermore. (Psalm 121:8 NRSV)

Above the entrance door of the building known as the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna is a mosaic of the Good Shepherd. The beardless Jesus is not depicted wearing the garments of a Palestinian shepherd but the imperial gold and purple of Rome. This Christ is simultaneously the good shepherd who lays down his life for the sheep (John 10:11) and the heavenly king who sits at the right hand of the Father (Mark 16:19).

This is not a narrative image but a symbolic representation of the Good Shepherd who, like the God of Psalm 121, protects the faithful throughout their life journey but who also transcends time and the physical world (Psalm 121:8). Jesus is the Word who ‘was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him’ (John 1:2–3). He is also Christ Pantocrator, the ruler of all places and times who offers salvation. His gold cross is a promise of resurrection and he sits upon rocks whose shapes evoke both mountains and tombs.

The sheep are at peace in the presence of the Good Shepherd. They relax amongst the verdant and life-giving sprigs. He is ‘the gate for the sheep’. Whoever enters by him will be saved (John 10:7, 9). This Shepherd has faced Gethsemane and has risen.

A golden semi-circle hovers between the grounded landscape and the dome of heaven. The dome represents the deep blue of sky and the infinity of heaven, as well as flowers of creation and life. There is a thin space between realities where earth and heaven, incarnate and transcendent, meet.

References

Dresken-Weiland, Jutta. 2016. Mosaics of Ravenna: Image and Meaning (Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner)

Freeman, Jennifer. 2015. ‘The Good Shepherd and the Enthroned Ruler: A Reconsideration of Imperial Iconography in the Early Church’, in The Art of Empire: Christian Art in Its Imperial Context, ed. by Lee M. Jefferson, and Robin M. Jensen (Minneapolis: Fortress Press)

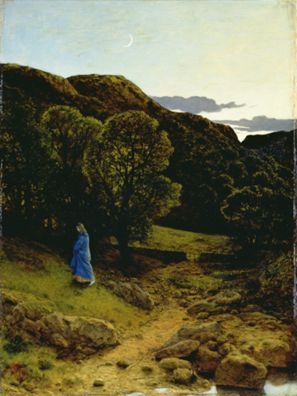

William Dyce

The Garden of Gethsemane, 1850s, Oil on millboard, 40.8 x 30.5 cm, National Museums Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery; WAG 221, National Museums Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery / Bridgeman Images

The Gateway

Commentary by Amanda M. Burritt

Viewing William Dyce’s Gethsemane, we are immediately drawn into a valley pressed in on all sides by rocky hills. A dirt path winds its way to a small gate in a low stone wall which delineates the inhabited space from the wild region beyond. The atmosphere is weakly illuminated by diffused light emanating from an unseen source. A crescent moon hangs in the sky above the hill. Jesus, looking downward, trudges up the slope. Although a relatively small figure, he is the poignant focus of the whole composition.

The Gospels recount Jesus’s anguish in the Garden as he prays to his Father before his imminent betrayal, arrest, and crucifixion: ‘Father, for you all things are possible; remove this cup from me; yet, not what I want, but what you want’’ (Mark 14:36 NRSV). Like the Psalmist, Jesus acknowledges the omnipotence of God (Psalm 121:7–8) and surrenders himself to the Father’s will (v.2).

Dyce’s work, set in his native Scotland, is not intended to be a literal rendition of the biblical narrative depicting an event in the Holy Land of first-century Palestine. Instead, Dyce shows us a scene that transcends any one place or time, not of one place and time but of all places and times. All landscape is sacred because, as Psalm 121 assures us, God created it. He is the Lord ‘who made heaven and earth’ (v.2 NRSV).

Dyce’s landscape is also sanctified by the footsteps of Jesus whose ordeal, as he moves toward death and resurrection, is understood by Christians to assume the struggles of all people. It is the eternal Creator of Psalm 121 who protects by day and night to whom Jesus the Son prays in his time of trial. Dyce’s Jesus occupies the Holy Land of faith, a place which is just as convincingly expressed in the identity of nineteenth-century Scotland as in ancient Palestine. Gethsemane confronts the universality of human fear and suffering and the response of an omnipotent and omnipresent God—a response revealed in the saving obedience of the one whose tribulations Dyce ponders.

References

Pointon, Marcia. 1976. ‘William Dyce as a Painter of Biblical Subjects’, The Art Bulletin, 58.2: 260–68

Frederic Edwin Church :

Pichincha, 1867 , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist :

Mosaic of the Good Shepherd and decorated vault, Early 5th century , Mosaic

William Dyce :

The Garden of Gethsemane, 1850s , Oil on millboard

Creator and Protector

Comparative commentary by Amanda M. Burritt

A key theme of Psalm 121, one of the group known as Psalms of Ascent, is the relationship of human beings to the divine and to the natural world. God is creator and defender, transcending time and place, aware of human fear and offering protection.

The Lord is your keeper;

the Lord is your shade on your right hand.…The Lord will keep you from all evil;

he will keep your life (vv.5, 7 NRSV)

Psalm 121 has generated much exegetical debate. Are the mountains the source of danger or of succour? Who is speaking? Pilgrim and priest or father and son? Does the Psalmist pose a question then answer it himself? Is this the internal dialogue of a traveller? Is it a conversation on the journey to Jerusalem? Is it a liturgical discourse for pilgrims who have safely arrived in the Temple in Jerusalem? Is it a reassurance for those concerned for the journey home?

Notwithstanding these scholarly discussions, profound truths of this psalm remain for people of faith—God created all that is. In all aspects of their journey of life God will protect those who have faith. Faithful pilgrims need not fear, nor seek other sources of protection apart from the God who created them.

Mountains are liminal spaces between earth and sky, heaven and earth. The God of Israel has a dwelling place in His Temple on the holy mount of Zion. The mountains of Psalm 121 are places of physical danger. Wild animals and robbers inhabit them and threaten the safety of the pilgrim traveller (‘evil’ lurks here (v.7)). Unlike the gods of the Canaanites who sleep in winter and return to wakefulness and life in spring, the God of the Psalmist is eternally awake, protecting those who have faith in Him (v.4). He is the one who made the land, the mountains, and, indeed, all of creation (v.2).

Mountains symbolize great age and their presence inspires awe. For the nineteenth-century traveller, mountains, such as the volcano Pichincha in Ecuador, exemplified the sublime in nature. They seemed insurmountable and as unknowable as the essence of the divine. They were also barriers to be conquered in the search for new land to explore and colonize.

These lands teemed with life, life which revealed the mysteries of creation (v.2) in often startling and confronting ways. Frederic Edwin Church painted at a time when science and religion were grappling with the revelations of evolutionary theory, natural selection, geological time, and the antiquity of ‘man’. His response was to depict rich and complex scenes which reflected both new scientific knowledge and a sense of awe and wonder.

The Galla Placidia Good Shepherd, William Dyce’s Gethsemane, and Church’s Pichincha are not narrative images. Each is to be understood through its symbolism, and the images of trust and vulnerability it conveys—the travellers in Pichincha, the incarnate Jesus in Gethsemane, and the sheep who look to the Good Shepherd for protection.

In Gethsemane, we see the incarnate one who seeks deliverance in the darkness. The darkness is physical although the moon is visible as night falls (Psalm 121:6). The true darkness in the painting is existential. Incarnation means being fully human with fully human emotions. Like the traveller in Psalm 121:1, Jesus prays for help in the garden of trial as he faces arrest and crucifixion. The traveller in the psalm ascends to Jerusalem. In Gethsemane Jesus begins his ascent to the Father through his ascent on the cross. For both there is a journey to be made through fear, doubt, and suffering.

The Good Shepherd of Galla Placidia ‘lays down his life for the sheep’ (John 10:11 NRSV). He knows the Father and the Father knows him (John 10:15; Psalm 121:7–8). He has passed through Gethsemane and has ascended as Christ Pantocrator, the ruler, saviour, and judge of all places and times.

God is present in the Temple and in the high mountains but God is not confined to them. They are sacred places, liminal and numinous, but all of God’s creation is sacred and interconnected. The fantastically composite Andean landscape of Pichincha depicts the lushness of creative life. The omnipresent and eternal God of the Bible is present in ancient Israel, nineteenth-century Scotland, and the wild places of the Americas. The Creator God’s being, presence, and actions are not confined to, or by, any one place, time, or culture (Psalm 121:8).

References

Greidanus, Sidney. 2016. Preaching Christ from Psalms (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans)

Commentaries by Amanda M. Burritt