Genesis 5

In the Image and Likeness of God

Antony Gormley

Event Horizon, 2007, 27 fibreglass and 4 cast iron figures, 189 x 53 x 29 cm, Installation view, Hayward Gallery, London; ©️ Antony Gormley. Photography by Gareth Fuller / PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Meeting the Maker?

Commentary by Holly Morse

Anthony Gormley (b.1950) makes his work in his own image. Cast directly from his body, not only do Gormley’s sculptures bear an uncanny likeness to the physicality of the artist—often requiring viewers to do a double take as they realize they have encountered a work of art, and not a human—their various locations, and the interactions they have invited, also give further anthropomorphic potential to these sculptures.

For Event Horizon, Gormley installed thirty-one fibreglass and iron casts of his body across the skyline of London, quietly looking down on thousands of people below. Despite the human likeness of the works dotted across the capital’s buildings, Gormley’s bodies create for passers by the feeling of being watched over from above, as if observed by angels or gods.

Gormley, the artist, makes work in his own form to encourage us to consider the specific qualities of humanness and the impact of humanity upon its surroundings.

YHWH, the creator deity of the Hebrew Bible, also creates in his image and likeness.

For centuries, people have wrestled with what it means for humanity—in Hebrew ‘adam—to be made in the ‘image’ (Genesis 1:27) and ‘likeness’ (Genesis 1:27; 5:1) of God, and have frequently concluded that these verses offer an inclusive representation of the closeness shared between God and all humans. If we ‘frame’ this biblical creative process with the help of the sculptures made by Gormley, we might imagine God as a heavenly artist, forming humans as reflections of himself.

Yet in both Gormley’s art and the creation accounts of Genesis 1 and 5, we are left to reflect on what it means for the whole of humanity to be imaged on a single entity, be that an individual artist or the creator deity.

How close are the creations to their creator? Does God fully imbue the humans he fabricates in his likeness with his own nature, or is humanity essentially different from its maker? Might there be some analogy between the way that Gormley’s casts cannot entirely replicate the artist and the ways that humanity is different from YHWH? Is being in the likeness of God a witness to human closeness to divinity, or evidence of our distance from it? After all, an image is never the exact replica of its original subject.

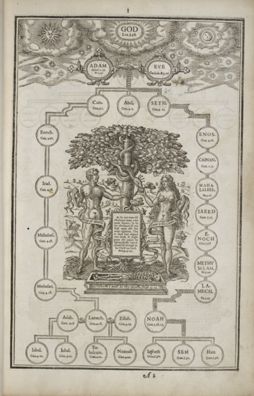

Unknown artist

First page of Genealogy, Adam and Eve, from The Genealogies Recorded in the Sacred Scriptures by John Speed, issued in Holy Bible, 1611, Engraving; LUNA: Folger Digital Image Collection, STC 2216, A2r, Folger Shakespeare Library; Digital Image: 46552

The Holy Family Tree

Commentary by Holly Morse

The first genealogical text of the Hebrew Bible, Genesis 5, has provided the foundation for many subsequent reiterations of the holy family tree for both Judaism and Christianity. It was a text that was probably originally written around the sixth century BCE by Israelite Priestly writers concerned to record their special elect status as the people of YHWH, long before the emergence of Christianity. For later Christian readers, these genealogies in Genesis 5 became the first links in a chain that ultimately led to Jesus Christ and, therefore, had a similarly prized place in their accounts of human history.

This Christian approach to the genealogy of Adam, and subsequent genealogies in the Hebrew texts, is perfectly illustrated in John Speed’s designs for the front material of the 1611 King James Bible. Reading Genesis 1, 2, and 5, Matthew 1, and Romans 5:9 together, the first page of Speed’s intricate series of genealogical images sees him highlight the importance of Jesus’s heritage, and thus his humanity, by carefully presenting him as ‘the Son of Man’, that is, of Adam. At the same time, Jesus’s divinity is also alluded to—God is mysteriously placed at the head of the family tree, and yet not connected to it—a clever visual play on the complex personhood of Jesus.

The divided genealogy of Adam, which we find split between Genesis 4 and Genesis 5 in the Hebrew Bible, is also faithfully represented. On the left side of Speed’s image, Cain and his corrupted line is presented, while on the right appears the righteous Seth, who ultimately forms the second link in the chain that leads to Jesus. Perhaps these two sides of the progeny of the first man, Adam, are offered here as a warning that there are two paths through life for a person—the path of the sinner and the path of the righteous, as well as a message to Christians about which one they should choose.

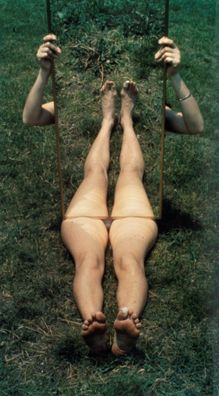

Joan Jonas

Mirror Piece I, 1969, Chromogenic print, 1016 x 565 mm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Purchased with funds contributed by the Photography Committee, 2009, 2009.31, ©️ Joan Jonas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York: DACS, London; Photo: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation / Art Resource, NY

Not in His Image

Commentary by Holly Morse

Joan Jonas (b.1936) uses her art to lament the ways in which women are constructed and objectified—denied the power to have autonomy over their own image.

In her Mirror Piece performances, several female performers are mostly hidden by the large oblong mirrors they carry. These mirrors make the audience’s attempts to rest their gaze on the women’s bodies uncomfortable and unsettling. Rather than encountering an uninterrupted feminine form, audience members see their own reflections staring back at them, surrounded by disconnected female body parts. All the while, male dancers carefully choreograph the female performers’ movements.

Jonas’s performances, then, offer a disconcerting remark on the fragmentation, even erasure, of female identity within Western society and culture.

As we glance from the photograph of Jonas’s Mirror Piece—a woman’s body image, broken—back to the opening verses of Genesis 5, we might reflect on the resonances this has with the only (and partial) presence of women in this re-telling of the beginning of humanity.

Although it is a text clearly concerned with what it means for us to be humans in relation to God, women are only conspicuous by their absence, and the first mother, Eve, is entirely erased. Although various modern translations of Genesis 5:1, such as the NRSV, lead us to believe that when God created humankind, he made them in his likeness, it is more accurate to the original Hebrew to read ‘he made him in the likeness of God’. It is only in Genesis 5:2 that we have a subsequent separation into male and female.

According to biblical scholar Phyllis Bird, when the Priestly writer uses ‘adam generically he is referring to a masculine identity, thus in his accounts of creation there is ‘no word on sexual equality … the representative and determining image of the species was certainly male’ (Bird 1981: 151). According to this reading of Genesis 5:1–3, Adam is the main inheritor of God’s ‘likeness’ (and his ‘image’ if we also read Genesis 1), and Adam alone can transfer his ‘likeness’ and ‘image’ to his male children (Genesis 5:3). The first woman, who was absolutely necessary for the birth of the first sons, is rendered invisible.

The first mother, then, shares a similar space to one of Jonas’s performers under a male gaze, hidden by the textual mirror of Genesis 5 as it reflects an ancient, masculine view of ideal humanity back out to today’s readers.

References

Bird, Phyllis. 1981. ‘“Male and Female He Created Them”: Gen 1:27b in the Context of the Priestly Account of Creation’, HTR, 74: 129–59

Antony Gormley :

Event Horizon, 2007 , 27 fibreglass and 4 cast iron figures

Unknown artist :

First page of Genealogy, Adam and Eve, from The Genealogies Recorded in the Sacred Scriptures by John Speed, issued in Holy Bible, 1611 , Engraving

Joan Jonas :

Mirror Piece I, 1969 , Chromogenic print

Who’s Who?

Comparative commentary by Holly Morse

Genealogies of the Bible tend to have a dull reputation; long, repetitive lists of men begetting men, over and over, generation to generation. The very first of these who’s whos of the Bible is found in Genesis 5, where the biblical text follows the story from the first man, Adam, created in the likeness of God, down to the first man to be joined in covenant with God, Noah.

Actually, it’s a list of great, even miraculous men. Men like Enoch, who mysteriously walked with God until ‘God took him’ (Genesis 5:24), and Methuselah, who at 969 years has the Bible’s longest lifespan. It is an idealized heritage for humanity, with those of Adam’s descendants tainted by Cain’s wrongdoing (Genesis 4) removed from history entirely.

Read in this way, this genealogy of the biblical ur-father communicates powerful messages about the super-humanity of Adam’s offspring, who lived long and were fruitful, and multiplied.

John Speed’s 1611 engraving underscores the continuing power of this view of Adam’s lineage (as a preparation for Christ) in Christian tradition.

However, when taken together, the three works in this exhibition caution us to read between the lines of Genesis 5’s venerable vision of men, and to draw out further significance from the text.

The writer is wrestling with questions—about human nature, how it relates to God, how important assets such as the ‘likeness’ of God are transmitted from person to person, and who is in and who is out of God’s favour. Indeed, whilst at first glance the text might offer a window into a distant utopian past, where humanity and its deity remained close—before God had to inflict punishment on the earth and its inhabitants (Genesis 6–9)—Genesis 5 can also be read as already containing all the ingredients of the coming disaster in which humanity is fractured.

On the surface, there is a perfect beginning. God brings into being a manifestation of divine wholeness by making a single human ‘likeness’, encompassing both male and female. Comparably, perhaps, Antony Gormley’s sculptural replications of his body invites us to find all humanity in their lineaments, whoever we are. But on closer inspection, might Genesis 5, like Gormley’s humanity, in fact provide us with something more problematic: a masculine history, in which it is the single masculine ‘adam—created before male and female—who is in God’s likeness, and only Adam’s male children who inherit this special quality?

Indeed, when the reading of the opening verse of Genesis 5 is extended to verse 3, we encounter a text that, along with its counterpart in Genesis 2:4b–25, forms part of a powerful legacy of ideas about creation and godliness in which the female body has been seen as defective and distanced from divinity. Genesis 5, with its male-dominated genealogy, reflects the male-dominated lines of monarchs and religious leaders of Western history, the men whose likeness to God afforded them special divine rights of power and prominence. Women, like the missing Eve of Genesis 5, have in the main been erased from the historical record—as the women in Joan Jonas’s performances are substantially hidden by the mirrors they hold up to the audience. Their challenge to viewers can also stimulate a challenge to readers of the biblical text: to discern, and rectify, wrongs only properly highlighted in recent years.

The genealogies of Genesis—whilst celebrating a special relationship between God and humanity—must also be handled sensitively, as they have the potential to be exclusionary in their imaging of humanity, and in particular, of righteous humanity. For it is not only women who are removed from Adam’s genealogy in Genesis 5. So are Cain’s kin (perhaps foretelling God’s troubling annihilation of many of Adam’s descendants in the flood of Genesis 6–9). While Cain, the first murderer, undoubtedly represents a criminal character worthy of punishment, his family’s erasure from the earth is the first of several instances in which the Bible (like Speed’s engraving) identifies ‘bad’ humanity in contrast to ‘good’. This division is not always made based on evil acts or wrongdoing, but (in later genealogies) on identity and election.

So, while genealogies can speak of the joy of connection to God, they can also speak of the power of specific groups and traditions. The various ways in which these expressions of joy and power are received and interpreted may be apparent if we consider the differences in perspective and worldview between the ancient world that produced these genealogies, their myriad reinterpretations by Jews and Christians throughout history, and their place in Jewish and Christian understanding today.

Genealogies, then, as texts about identity and inheritance, must come with a warning. While they can tell us who we are and where we come from, they simultaneously have the power to exclude and to alienate.

Commentaries by Holly Morse