1 Peter 2:1–10

A Living Stone and a Chosen People

Works of art by Michelangelo Buonarroti, Unknown artist and Unknown Syrian or Palestinian artist

Unknown artist

Theodor Metochites presenting model of the church of the Chora to Christ, 1315–21, Mosaic, Kariye Camii, Istanbul; robertharding / Alamy Stock Photo

‘Built into a Spiritual House’

Commentary by Anna Marazuela Kim

In an act combining splendour and humility, a richly appointed figure kneels before Christ, presenting a model of the very same church in which the scene is depicted. In the centre, Christ Pantokrator sits enthroned, Bible in one hand and the other hand raised in blessing. The glittering mosaic with its golden background reflects the heavenly realm of Christ, as well as the magnificence of the patron.

The kneeling figure in the splendid hat is Theodore Metochites (1270–1332), Byzantine poet, humanist, and statesman. He is credited with restoring the church of the Chora Monastery, also known by its Turkish name, Kariye Camii. Now a national museum, the renovated church, with its richly restored mosaic programme, is considered one of the most important Byzantine monuments after Hagia Sophia.

The mosaic of the church presented to Christ is one of two installed by Metochites at the Chora. Likely to have been founded in the sixth century, the Chora, along with Constantinople itself, had fallen into serious disrepair. In the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, private patrons attempted to restore the glory of the city and its religious monuments, as an expression of piety and a safeguard for their salvation.

Describing his effort, Metochites wrote:

This monastery [of the Chora] has meant more to me than anything in the world; it is so now and will be in the time to come. It was a work of noble love for things good and beautiful, and assured a truly secure profit and wealth for the soul. (Evans 2004: 17–18)

The Chora church is widely considered a masterpiece of this Palaiologan renaissance. ‘Chosen and precious’, it witnesses to the ‘chosen and precious’ Christ evoked in 1 Peter (vv.4, 6). However, just as in Metochites’s time, preserving its artistic programme is an ongoing process. While a landmark restoration in 1948 revealed the magnificent mosaics and frescoes visible today, due to their current state of decline, Kariye Camii is on the World Monuments Fund’s list of the 100 Most Endangered Sites.

References

Evans, Helen (ed.). 2004. Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557) (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Michelangelo Buonarroti

Rondanini Pietà, 1553–64, Marble, 195 cm, Museo della Pietà Rondanini, Castello Sforzesco, Milan; Photo: Mauro Magliani, 1997

‘Rejected by Mortals’

Commentary by Anna Marazuela Kim

In the last decades of his life, Michelangelo undertook what we believe to be his last sculpture. At the Palazzo Rondanini, where it was first displayed, it was mistakenly described as a ‘modern group, roughed out and said to be the work of Michelangelo’ (Fiorio 2014: 14). The sculpture is such a radical departure from previous works that it was attributed to the artist only in 1807. It remains an enigma today.

Rather than the polish and perfection of his Vatican Pietà, what confronts us here are two severely attenuated figures. Their rough surfaces read like bodies flayed in stone. The Virgin Mary hovers above her son, enfolding his flesh mysteriously into her own. Two beautifully formed legs and a severed arm suggest an earlier version of Christ, once envisioned in classical, heroic terms. This initial figure was presumably destroyed by the artist himself in progressive stages of carving, and provides a glimpse of what might have been a very different work.

Michelangelo's Rondanini Pietà has been described as a ruin and a tragedy by art historians. The missing limbs and hollowing out of bodies suggest not a lack of finish or incompletion, but a deliberate act of violence. Of all artistic forms, sculpture—as a subtractive process—highlights the blurring of boundaries between making and breaking. That emphasis is doubled in the Rondanini, where the process of breaking is not limited to freeing figures from the marble block, but also to their destruction.

But whether the result is tragic depends upon what is being staged here. The rich palimpsest of surfaces and forms inscribed in these remains render visible a powerful series of artistic choices, generally hidden from view. These bring us close to the hand and the mind of the artist, as he attempts in this, the last artwork he made before his death, to give form to the mystery of Christ’s passion.

The sculpture appears to have been undertaken without commission. It remained with the artist until his death, suggesting it was a highly personal study. Perhaps it was part of the same process of spiritual self-examination that is expressed in Michelangelo’s sonnets.

And like the stone rejected by mortals in Peter’s exhortation, the sculpture which was once deemed a ruin is now prized as one of the artist's most precious works.

References

Fiorio, Maria. 2014. The Pietà Rondanini (Milan: Electa)

Unknown Syrian or Palestinian artist

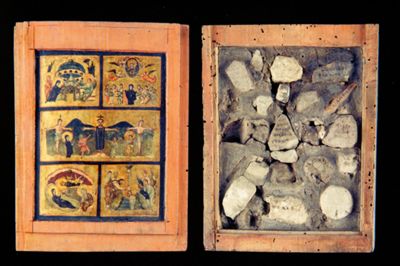

Wooden Reliquary Box with Stones from the Holy Land, 6th century, Carved wood, engraved and partially gilded; encaustic painting on wood, 24 x 18.4 x 1 cm, Chapel of St Peter Martyr Museo Sacro, Musei Vaticani; From the Treasury of the Chapel of the Sancta Sanctorum, Lateran Palace, Rome, Cat. 61883, History and Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

‘A Living Stone’

Commentary by Anna Marazuela Kim

Like many early Christian artefacts, the Palestine box is deceptively humble in appearance, yet charged with spiritual potency. Currently held in the Vatican museums, for centuries the box was kept in the Sancta Sanctorum, the chapel of the fourth-century Lateran complex in Rome. An important site of pilgrimage for the Christian faithful, its treasures took on renewed significance after the fall of the Holy Land in the twelfth century.

The sixth-century box is one of the oldest surviving examples that testifies to a centuries-old practice of collecting souvenirs from the region that continues today. Stones and a splinter of wood, embedded in an ersatz landscape, illustrate the special status accorded holy sites (loca sancta) associated with the life of Christ.

Much like a relic, each object has an inscription which identifies the place from which it was taken, here written in Greek. A splinter of wood jutting on a diagonal is labelled ‘Bethlehem’; the rock in the centre, ‘the place of the Resurrection’ (or the Holy Sepulchre). At top right, a horizontal stone is said to be from the ‘Mount of Olives’. One at the bottom is inscribed as ‘Zion’, a name that seems likely to refer to the citadel on Mount Zion, the site of the Last Supper.

Seven small but carefully rendered paintings decorate the lid of the box. These depict biblical scenes from the life of Christ, which unfold in the places from which the objects were gathered. At the centre, the most prominent of the paintings stages the Crucifixion. Below, two paintings show the earlier Nativity of Christ and the Baptism, respectively. And fittingly, above, we witness the discovery of the empty tomb and Christ's Ascension. From the shape of the lid and the paintings’ remarkable state of preservation, we can infer that the paintings faced down rather than up, nearly touching the fragments of the holy places to which they refer (Nagel 2010: 218).

In this way, the lifeless matter of earth and stone come alive again, returned to their original, holy landscapes, transporting the faithful viewer.

References

Nagel, Alexander. 2010. ‘The Afterlife of the Reliquary’, in Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics, and Devotion in Medieval Europe, ed. by M. Bagnoli, et al (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Unknown artist :

Theodor Metochites presenting model of the church of the Chora to Christ, 1315–21 , Mosaic

Michelangelo Buonarroti :

Rondanini Pietà, 1553–64 , Marble

Unknown Syrian or Palestinian artist :

Wooden Reliquary Box with Stones from the Holy Land, 6th century , Carved wood, engraved and partially gilded; encaustic painting on wood

From Rubble to Renewal

Comparative commentary by Anna Marazuela Kim

Peter's exhortation to come to Christ, a ‘living stone’ (lithon zōnta) and build a ‘spiritual house’ (oikos pneumatikos) must be understood within the context of the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple by the Romans in 70 CE. He reminds the faithful that, more than the physical building, it is the people themselves who constitute the true edifice, which is a spiritual one. In the aftermath of devastation and displacement, the life of the church can be rebuilt: not from the rubble that remains, but from these ‘living stones’.

After the fall of the Holy Land in the twelfth century, Christians experienced a similar displacement and exclusion from the place at the origin of their religious history. Centres of pilgrimage throughout Western Christendom sought to replicate the sacred experience of this inaccessible destination, at times recreating entire landscapes of devotion. On a smaller scale, the Palestine box enables a form of topographical travel for the devotional beholder to the Holy Land. Vivid pictures animate the imagination to ‘see’ Christ as the perpetually living sacrifice. Stone, charged with the holiness of what it has touched, acts as a conduit to bring the faithful into contact with the land which witnessed these events. By means of substitution, ordinary materials become extraordinary, alive with spiritual potency.

For many centuries, mosaics have been employed in the decoration of Christian churches, in particular, the surfaces of their lofty, domed apses: spaces that symbolized, and visualized, the eternal realm of the Heavenly Jerusalem. The specific materiality of mosaics—their uniquely reflective capacity, glowing when illuminated, as if divinely lit from within, gem-like in their rich glittering colours—made them especially suited to the depiction of the sacred.

The ongoing restoration of the Chora church provides a compelling metaphor for Peter's idea of a church made of ‘living stones’. First, it highlights the need for the faithful to continuously build their spiritual house, through sacrifice and pious deeds. But the unique method by which mosaic is restored also provides a potentially rich hermeneutical device for understanding this idea. For, with the insertion of new tesserae, even the most damaged mosaics may be renewed, restored to their original radiance and potential to reflect Christ’s glory.

The final part of 1 Peter 2:1–10 reminds its readers that the stone which founds the Church can also prove a stumbling block, to those who fail to follow God's word. Throughout Scripture (e.g. Luke 19:40; Leviticus 26:1), and in the subsequent history of Christian art, stone manifests this duality: as a medium with the potential for religious expression, but also for idolatry. The biblical injunction against the graven image became the foundation for the rejection of Christian sculpture in the Eastern Church, and later within a Reformed one.

Within this frame, Michelangelo’s choice to ‘break’ the beautiful body of Christ takes on another meaning. In his monumental image of the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel, the artist was praised for showing the beauty and perfection of the human body in every imaginable form. But he was also castigated for this display of artistic virtuosity; condemned for placing his own art above the Christian beliefs he sought to animate. Towards the end of his career, Michelangelo's sonnets reflect upon the spiritual perils of the imagination, or fantasia—the source of artistic inspiration, but also of error and sin.

Perhaps, then, we might see in the non-triumphant Rondanini Pietà not a tragic ending, but a spiritual turning: from the idolatry of the celebrated artwork carved in stone, to its animation by pious reflection. In this final meditation on the mystery of the Passion, in its inward-turning iconoclasm, an idol of art is transformed into a living icon.

Commentaries by Anna Marazuela Kim