Exodus 20:4–6

The Second Commandment

Unknown Byzantine artist

Icon on the Triumph of Orthodoxy (Icon of the Sunday of Orthodoxy), Late 14th century, Egg tempera and gold on panel, 39 x 31 cm, The British Museum, London; 1988,0411.1, © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Victorious Icons

Commentary by Anna Carroll

Between 726 and 787 CE and again between 814 and 842 CE, the Byzantine emperors banned icons, seeming thereby to honour the second commandment. Icons were removed from churches and figurative mosaics were plastered over.

These two periods of iconoclasm were in part a response to economic and military hardships. As the empire lost territory, anxieties developed about a withdrawal of divine favour as a result of the improper use of images.

Then, in 843, Empress Theodora restored the making and use of images in an event called the Triumph of Orthodoxy, which is commemorated in the overtly iconophilic Icon with the Triumph of Orthodoxy.

The example from the British Museum, shown here, makes explicit reference to the restoration of icons by showing this Hodegetria icon being processed through Constantinople, as it was in the celebrations of 11 March, 843. Theodora and her son Michael III, champions of the iconophiles, participate. In the top register is the Hodegetria icon—an icon of the Virgin and Child believed to have been painted by St Luke. Below them is a group of saints, at the centre of which St Stephanos the Younger and St Theodore the Studite hold aloft an icon of Christ. Finally, at the left of the group, St Theodosia grasps another icon showing the Hodegetria image.

Icon with the Triumph of Orthodoxy is thus three icons in one. It unabashedly proclaims its support for icons, presenting the viewer with a profusion of figurative imagery.

This multiplicity of icons assured viewers that icons were pious. In the post-iconoclastic period, images that praised iconophiles and showed holy figures using icons convinced people of the trustworthiness of images.

This object, with its many icons within an icon, makes a strong case for iconophilia. After the Triumph of Orthodoxy, there was no fear of making the ‘likeness’ of the holy ones who were ‘in heaven above’ (Exodus 20:4). Images had been sanctioned by church and state, as visualized here; if the saints use icons, then they must be proper tools for worship.

References

Cormack, Robin. 1985. Writing in Gold: Byzantine Society and its Icons (London: George Philip)

Kotoula, Dimitra. 2006. ‘The British Museum Triumph of Orthodoxy Icon’, in Byzantine Orthodoxies: Papers from the Thirty-sixth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, University of Durham, 23–25 March 2002, ed. by Andrew Louth and Augustine Casiday (London: Routledge), pp.121–30

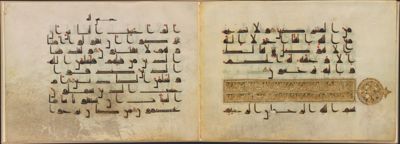

Unknown artist

Fragment from an Early Tenth-Century Qur'an, Before 911, On vellum, 230 x 320 mm, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; Purchased by J. P. Morgan, Jr., 1915, MS M.712, fols. 19v–20r, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Celebrating Calligraphy

Commentary by Anna Carroll

This page from a tenth-century Qur‘an is part of a manuscript donated by Abd al-Mun im Ibn Ahmad to the Great Mosque of Damascus in July, 911 CE. Here, Surah (chapter) 29, ‘The Spider’, is written in curving calligraphic script. This Surah likens worshippers of gods other than Allah to spiders, suggesting that the protection offered by a false god is as flimsy as a spiderweb. The golden rectangle, with a brilliant orb at its right end and densely written script within, is the heading of Surah 29.

There is no figurative decoration. In this, the illuminated page conforms to a Muslim prohibition against graven images. Islamic artists were tasked with beautifying religious objects without using representational imagery; in the secular realm figures were acceptable, but sacred art typically followed the commandment more literally. The Hadith says, ‘Those who paint pictures would be punished on the Day of Resurrection and it would be said to them: Breathe soul into what you have created’ (Sahih Muslim, Book 24, Hadith 5268). Artists would be punished for presuming to create as God did when they were unable to bring those creations to life. This is close to the way that the commandment in Exodus 20:4 forbids the crafting of images of that which God has created.

So, Islamic artists developed elaborate decorative scripts instead. Such scripts provoked an initial backlash for defying the Hadith, but became increasingly popular and were soon accepted for their aesthetic value. Calligraphy was distinct from ornamentation because it was not an additive element, but merged text and illumination. Calligraphic writing glorifies the Word of God directly, instead of relying on additional decoration to beautify a more simple script.

The lines are not simply decorative, but are essential to the text. The word remains the primary element, and the decorative aspects are subsidiary, allowing Islamic artists to manipulate the visual form of the word and honour God through calligraphy. While some Qur‘ans feature vegetal motifs and animals, the human figure was consistently avoided in sacred books and in architectural religious decoration.

Early Christian writers interpreted the second commandment as a reminder to ‘worship none other than the supreme God who made heaven and everything else’ (Origen, Against Celsus 5.6). This fragment is an example of how artists in a different religious tradition sought to achieve the same end.

References

Chadwick, Henry (trans). 1953. Origen: Contra Celsum (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Ettinghausen, Richard, and Oleg Garber. 1987. The Art and Architecture of Islam: 650–1250 (Penguin Books: England)

Siddiqui, Abdul Hameed (trans). 1971–75. Ṣaḥiḥ Muslim; being traditions of the sayings and doings of the prophet Muhammad as narrated by his companions and compiled under the title al-Jāmiʻ-uṣ-ṣaḥīḥ (Lahore: Sh. Muhammad Ashraf)

Whelan, Estelle. 1990. ‘Writing the Word of God: Some Early Qur’an Manuscripts and Their Milieux, Part I’, Ars Orientalis, 20: 113–47

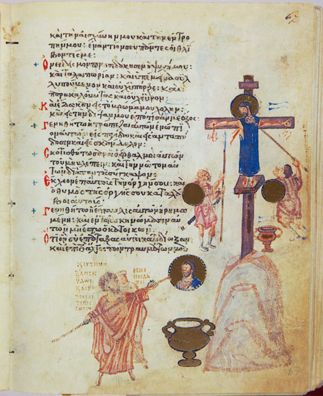

Unknown Byzantine artist

The Iconoclasts and the Crucifixion, from The Chludov Psalter , c.850, Tempera on vellum, 195 x 150 mm, State Historical Museum, Moscow; MS. D. 129, fol. 67r, © State Historical Museum, Moscow

Vandalizing the Byzantine Iconoclasts

Commentary by Anna Carroll

The Chludov Psalter boasts curious marginalia that are distinct from the larger miniatures more typical of Byzantine manuscripts. These small illuminations, which abound with likenesses of that which is ‘in heaven above’ and ‘in the earth below’ combine biblical themes with a visual history of Byzantine iconoclasm. Occupying a liminal space between text and page, they blur the boundary between biblical and contemporary times.

This folio features a verse from Psalm 69: ‘they gave me poison for food and for my thirst they gave me vinegar to drink’ (v.21). It is a psalm that Christian tradition links with Christ’s Passion (John 19:28–30). No surprise, then, that the page is dense with Crucifixion imagery.

Who is the figure at the bottom of the page who imposes himself upon the scene? His face has been rubbed away in an act of damnatio memoriae (‘condemnation of memory’). His hair splays out around his head—its wild and untamed appearance perhaps signalling (and condemning) an inner and spiritual disorder. He lifts a long pole surmounted by a circular shape which is decorated with an image of Christ. The wild-haired figure suspends this icon above a vessel of white liquid.

The man supporting the image of Christ is John the Grammarian, a dishonoured iconoclast about to whitewash an icon of Christ by plunging it into a tub of plaster. John threatens the image of Christ, whose likeness and incarnation makes God visible; the illumination vilifies John, whose assault on images becomes a new example of the sorts of ‘iniquity’ that—in a Christian dispensation—could be committed by ‘those who hate [God]’ (Exodus 20:5).

Subsequent readers eventually destroyed John’s image, rubbing out his face so that it is now barely visible. For his attempts to efface an image of Christ, it is John the Grammarian himself who has been all but erased.

References

Brubaker, Leslie. 2012. Inventing Byzantine Iconoclasm (Bristol: Bristol Classical Press)

Unknown Byzantine artist :

Icon on the Triumph of Orthodoxy (Icon of the Sunday of Orthodoxy), Late 14th century , Egg tempera and gold on panel

Unknown artist :

Fragment from an Early Tenth-Century Qur'an, Before 911 , On vellum

Unknown Byzantine artist :

The Iconoclasts and the Crucifixion, from The Chludov Psalter , c.850 , Tempera on vellum

Artists versus Commandments

Comparative commentary by Anna Carroll

The second commandment complicates representational art in the so-called Abrahamic religions because of the many ways it has been interpreted, including as a condemnation of graven images (specifically, images made to be worshipped), and—more radically—as a prohibition against the representation of any of God’s creatures.

Christian and Jewish artworks have often been willing to depict humans, animals, and plants from biblical narratives. And while there is a prevailing misconception that Islamic art is entirely aniconic, there are examples of Islamic figurative art from early in the religion’s history.

Crucially, none of these images was meant to be worshipped, for (despite their differences) the use of images as idols was a major concern in all of the religions in which they were made.

So what ramifications has the commandment had for artists in the Abrahamic traditions?

In Christianity, figurative images have been considered dangerous for many reasons, including the Incarnation. God made himself incarnate in Christ, who, since the Council of Nicaea (325 CE), was declared to have two natures, one divine and one human. Because Christ was divine, in depicting him, artists might have seemed (heretically) to be claiming that they were capable of capturing God in visual form; the visualization of God or God’s creations suggested the inscriptibility of a divine essence that is uncontainable. Conversely, iconophiles like St John of Damascus argued that by revealing himself in human form, God sanctioned the depiction of that human nature.

More prominent in Islam was an issue of hubris. Idols, as images of God meant to be worshipped, were clearly impermissible. But what of representations of people, plants, and animals? When considering these latter types of image the Hadith, or ‘Traditions of the Prophet’, stated that artists were unable to ‘breathe life’ into them. Only God can create. For artists to make figurative art would be too strive for a power too similar to God’s, and this was considered disrespectful to divine creation. So Islamic artists were careful not to represent perfectly that which had been made by the divine, and developed methods to abide by the commandment, such as disrupting or distorting figures (Schick 1998: 87).

Despite such concerns, the Byzantine and Islamic worlds continued to produce figurative art. For this reason, debates in Byzantium over the commandment recorded in Exodus 20 dominated the eighth and ninth centuries, and periods of official iconoclasm disrupted artistic production. While all figural imagery was subject to scrutiny, icons, like those incorporated within the British Museum’s Icon with the Triumph of Orthodoxy, were under the greatest suspicion.

As representations of holy figures, such icons were considered dangerous because they could be used idolatrously. They could misdirect veneration by encouraging the conflation of the physical object with the holy figure. Iconophiles who supported the use of sacred images in worship argued that icons were tools for worship that acted as a visual reminder of God or the saints, but were not the actual object of worship. Iconoclasts found this differentiation too subtle and encouraged the prohibition and destruction of icons.

When icons were permanently restored by the Orthodox Church in 843 CE, the newly empowered iconophiles commissioned art that championed their position. Manuscripts like the Chludov Psalter—produced less than a decade later—boast the victory of the iconophiles.

In the Islamic world, figurative imagery was largely relegated to the secular realm, but certainly did exist. In sacred contexts, aniconic (non-representational) motifs like arabesques were what typically decorated spaces and objects. Arabesques, ornamental designs comprising interconnected curving lines, often resembled writing. In sacred spaces like mosques, they tended to be based on the Qur’an and contained verses written out in elaborate calligraphic scripts in various mediums, including mosaic decoration.

Sidestepping the ban on representation, the words themselves became the art object from as early as the sixth century. They were written by human hands but they were spoken and created by God. The Word of God was used to beautify itself, restricting the true power of creation to God, and positioning the human artist as a scribe in service to the divine.

We see in these three works how artists in the Orthodox Christian and Islamic medieval worlds—inheriting the stern prohibition in Jewish Scripture— responded to a shared divine commandment. Marshalling stylistic conventions and theological arguments in support of motifs that could be both aniconic or iconic, each nevertheless sought to be faithful to the biblical prohibition against the misuse of graven images.

References

Cormack, Robin. 1985. Writing in Gold: Byzantine Society and its Icons (London: George Philip)

Flood, Finbarr Barry. 2016. ‘Idol-Breaking as Image-Making in the “Islamic State”’, Religion and Society: Advances in Research, 7: 116–38

Schick, Robert. 1998. ‘Archaeological Sources for the History of Palestine: Palestine in the Early Islamic Period: Luxuriant Legacy’, Near Eastern Archaeology, 61. 2: 74–108

Commentaries by Anna Carroll