Exodus 17:1–7; Numbers 20:1–13

Striking the Rock

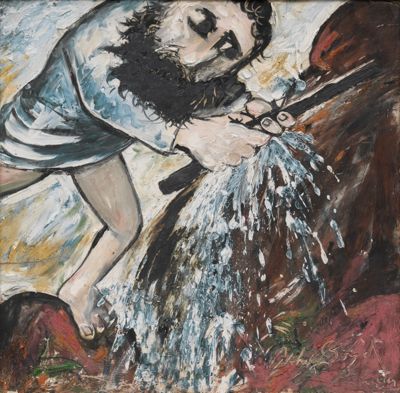

Arthur Boyd

Moses Striking the Stone, 1951–52, Ceramics, earthenware, coloured slips, 57 x 57 cm, National Gallery of Australia; Gift of Denis Savill 2012. Donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program, NGA 2012.819, Photo courtesy National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; Reproduced with the permission of Bundanon Trust.

A Loss of Control

Commentary by Diana Lipton

Arthur Merric Bloomfield Boyd (1920–99) was born into an Australian artistic dynasty. His works addressed universal themes such as love, loss, and shame, but also issues particular to Australian society, such as the fate of people of mixed Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal parentage. This latter work was painted on an earthenware ‘tile’ measuring 57cm square, with coloured slips and a clear glaze. The choice of this earthy medium may reflect the artist’s sense of connection to the land.

It’s hard to read the expression on the face of Boyd’s Moses. Is he angry, frustrated, confused, determined? We can’t be sure. Thick and black, more weapon than wand, Moses grasps the rod firmly at the centre with both hands. As Boyd depicts it, brute force made the water spring forth, and as much as the rock, Moses’s rod seems to be its source.

Water’s everywhere—drenching Moses’s hands and splashing his feet. Even the sky behind him and the tunic that clothes him share the colours of this elemental cascade. But the effect is far from blessed abundance. The absence of busy Israelites filling vessels or scooping and lapping up the water alongside their thirsty animals gives the scene an ominous dimension. The water threatens an imminent, overwhelming deluge beyond Moses’s control. Without his brother Aaron to share the blame (cf. Numbers 20:2, 10, 12), all the pressure is on Moses, and it’s apparently more than he can handle. His body is crammed awkwardly into the composition, and partially cropped by it. He balances precariously with one bare foot on a rock that must already be wet and slippery. His fall seems imminent.

Boyd’s Moses brings to mind the Little Dutch Boy whose finger could only stop up the dyke for so long, or King Cnut, who could not turn back the tides. He’s in danger of being submerged. This moment of disobedience (Moses struck the rock instead of speaking to it as commanded in Exodus 17:7), or faithlessness (he did not trust God enough to affirm God’s sanctity; v.12), will signal the end of Moses’s long and arduous career as Israel’s leader, depriving him into the bargain of the satisfaction of setting foot in the Promised Land to which he’d spent forty years leading his rebellious flock. How perfectly Boyd captures that moment.

Unknown artist

Jonah Sarcophagus, Late 3rd to early 4th century, White marble, 66 x 223 x 19 cm, Musei Vaticani, Vatican City; MV_31448_0_0, Alinari / Art Resource, NY

A Gift of Life

Commentary by Diana Lipton

The water is flowing but the Moses of the so-called Jonah Sarcophagus still holds his rod aloft, a further continuation of his already extended right arm. There’s no hint of exertion on his part; this strike must have been a tap, not a whack.

Exodus 17 suggests a ritual component to this event: ‘Pass on before the people, taking with you some of the elders of Israel; and take in your hand the rod with which you struck the Nile, and go. Behold, I will stand before you there on the rock at Horeb’ (vv.5–6).

But here there’s no element of ceremony. The fact that the sarcophagus artist overlooked it is understandable. In Exodus’s narrative context, the striking of the rock was a divinely stage-managed response to the people’s question, implied at the beginning of the episode and stated explicitly at the end: ‘Is the LORD present among us or not? (17:7). But here on the sarcophagus, the question of God’s presence is eclipsed by the people’s other, earlier question: ‘Why did you bring us up out of Egypt to kill us [in Hebrew, me and my sons] and our livestock with thirst?’ (v.3). They speak as though death by dehydration in the wilderness is a foregone conclusion.

The three figures (perhaps a father and sons as in verse 3’s original Hebrew), shown scooping the water into their mouths with their hands, are an answer to that question. But also, in this context, they are an answer to a question that plausibly preoccupied the sarcophagus artist: will the dead be resurrected? These three men were ‘dying of thirst’. Water sprang forth from the rock, they drank and—with all that entails—they lived.

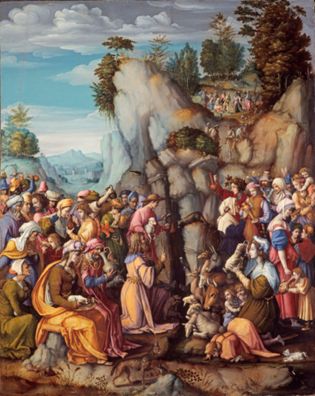

Bacchiacca

Moses Striking the Rock, After 1525, Oil and gold on panel, 100 x 80 cm, National Galleries Scotland; Purchased 1967, NG 2291, © National Galleries of Scotland, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

A Miracle of Presence

Commentary by Diana Lipton

Bacchiacca’s painting of Moses striking the rock is notable for its extraordinary variety of people, animals, and vessels. The clothing, head coverings, and jewellery that so engaged Bacchiacca reflect the fact that this crowd is drawn from all strata of society: nobles, peasants, and everything in between. Most probably, according to the courtly artistic practice known as maniera, these are imitations of diverse figures in works by other artists of his day.

But the artist aims far beyond aesthetic gratification. The variety of social and physical types ensures that Bacchiacca’s cast of characters is no homogenous band of wilderness wanderers bent on quenching their thirst, but an eclectic assembly of pilgrims, coming from the four corners of the earth to participate in a miracle.

The animals he portrays may have been based on studies from the menagerie of Duke Cosimo I de' Medici of Florence, or made after earlier works Bacchiacca had painted in the Duke’s palace. Here, however, they reflect the infinite variety of God’s creation: from the tiny lap dog drinking from a noble lady’s platter (bottom left); to the lamb in the arms of a shepherd (centre) that may recall the agnus dei of John 1:29 or the lost sheep carried home in Luke 15:5–6; to the giraffe (top right) inspired by a gift (probably by the sultan of Egypt) to the private Medici zoo in 1487. These creatures—like their human counterparts—have come from far and wide to partake in the miracle. A homogenous flock of thirsty sheep and goats—though they would have been more likely attendants at the biblical event—might have downgraded the miraculous water; they could have seemed too ordinary by far. Bacchiacca’s extraordinary menagerie elevates it.

Finally, and most importantly, there’s the variety of vessels, from simple ceramic bowls (centre right) through ornate glass pitchers (lower right) to highly decorated jugs (centre left) such as the artist’s father perhaps made—his father, Ubertino di Bartolomeo (c.1446/7–1505), was a goldsmith. The vessels could owe their prominence to the painting’s possible original commission by a guild of jug makers. But, again, theology prevails. These people aren’t coming to drink. They’ve come equipped with a fabulous range of empty vessels, the best that each can muster, ready to fill with the miraculous water that confirms God’s presence in their midst.

Arthur Boyd :

Moses Striking the Stone, 1951–52 , Ceramics, earthenware, coloured slips

Unknown artist :

Jonah Sarcophagus, Late 3rd to early 4th century , White marble

Bacchiacca :

Moses Striking the Rock, After 1525 , Oil and gold on panel

Three Strikes

Comparative commentary by Diana Lipton

Moses strikes a rock on two separate occasions, once soon after the Israelites leave Egypt (Exodus 17:1–7), and again just before they enter the Promised Land (Numbers 20:2–13). There are significant differences between these two narratives, most notably the fact that in Exodus God orders Moses to strike the rock (17:6) while in Numbers Moses strikes the rock (20:11) in defiance of God’s command to speak to it (v.8). But beyond the miracle that underlies both narratives, there are also significant similarities: the Israelites fear death in the wilderness (Exodus 17:2–3; Numbers 20:2–4); they doubt God’s presence in their midst (Exodus 17:7; Numbers 20:12); and there is a dispute (Exodus 17:2, 7; Numbers 20:3, 13).

These similarities generate a question about visual representations of Moses striking the rock: which narrative is being represented? Titles and contexts may not be original and are not determinative. As a rule, works in which Moses’s anger is an explicit theme—signalled perhaps by how he holds his rod—are likely to be inspired by Numbers 20, where his anger translates into a twofold striking of the rock (v.11) to which he should have spoken (v.8). Moses exhibits anger in Exodus 17 (v.4) too, but there the striking of the rock is not an expression of emotion; he is simply following God’s command (v.6). If Moses’s anger is not an explicit theme, the artist is probably representing Exodus 17, where the miracle is untainted by Moses’s disobedience and his subsequent failure to enter the Promised Land (cf. Numbers 20:12).

Yet a qualification is in order. When it comes to visual representations, the boundaries between these two narratives are porous. Details drawn from Numbers 20 seep into representations of Exodus 17. For example, in Exodus 17 the people ask Moses why he brought them out of Egypt to kill them, their children, and their livestock with thirst (v.3), but they request water only for themselves (v.2), and they alone, not their animals, drink (v.6). Numbers 20 by contrast reports that both the people and the animals drink (v.11), so a visual representation of Exodus 17 that shows animals drinking was plausibly influenced by (images of) Numbers 20.

The so-called Jonah Sarcophagus originated in Rome at the end of the third century and is the oldest known representation of Moses striking the rock. There are several indications that the artist associated this latter image with death and resurrection. The Israelites are dying of thirst; with no time for vessels, they are using their hands to scoop up the water. The scene is surrounded by others that that depict death, near-death or symbolic death, and resurrection, most obviously Lazarus (top left), and Jonah, whose three days in the fish’s belly are analogous in Christian typology to Jesus’s three days in the tomb. And finally, there’s the context: a sarcophagus.

Moses striking the Rock by Bacchiacca, was painted sometime after 1525. Bacchiacca was born into a Florentine family of painters, goldsmiths, and embroiderers, and worked as a decorative artist as well as a painter, which helps explain his passion for detail. His focus in our painting seems to be God’s presence. His assembled masses are emphatically not shown dying of thirst. Only one (lower right) is lapping up the water, and many are not drinking at all. These are exquisitely clad and bejewelled pilgrims, equipped with an astonishing variety of vessels ready to be filled with the miraculous water.

Though not a religious man, Arthur Boyd was attracted to the Bible, perhaps by its abundance of intense personal struggles, often tinged with danger. His many portraits of Jonah fall into this category, as does Moses Striking the Stone (1951–52). Boyd’s Moses is a solitary figure who grasps his rod—a far cry from Bacchiacca’s delicate gold pointer—in both hands. The water that spurts forth from his rock speaks less of divine blessing, as for Bacchiacca, or the hope for life eternal, as on the Jonah sarcophagus, than loss of control.

Not only are all these different interpretations supported by the biblical text, but each artist makes accessible an aspect of the narrative that, though strongly present, can easily get lost in the confusion.

Commentaries by Diana Lipton