Matthew 16:13–23; Mark 8:27–33; Luke 9:18–22

The Keys to the Kingdom

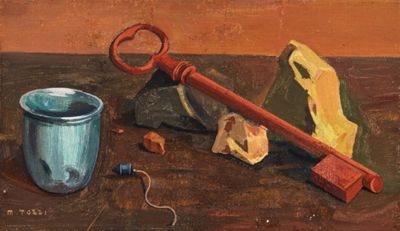

Mario Tozzi

Still life with a key, 1938, Oil on canvas, 19 x 43 cm; Private collection, Image courtesy of Archivio Tozzi

A Key at the Centre

Commentary by Roald Dijkstra

When Christ told Peter that he would give him the keys of the kingdom of heaven (Matthew 16:18–19), no actual keys were there. It was a promise, to be fulfilled later.

This promise prompts many questions (though not ones raised in the Gospel text itself): what kind of keys should we imagine and which lock might they open or close? Or was it just a metaphor? It is hard, however, to make a mental or visual representation of the story without thinking of ordinary keys. The keys become, nolens volens, central to the scene.

This is also the case in this composition by Mario Tozzi. A key dominates the scene, which also comprises a small rock split in pieces, a simple cup, and a plumb line. With his question ‘Who do people say that the Son of Man is?’ (Matthew 16:13), Jesus plumbed the thoughts of his disciples and their courage to confess. A rock is a symbol of strength, but here it is broken. Peter, whose very name (Petros or ‘rock’) reminds us of Christ’s image of him as the rock of the church (v.18), was not as strong as the metaphor in Matthew 16:18 might suggest. His weakness would be revealed soon afterwards, when Christ had to drink the cup of suffering (Matthew 26:39) and Peter denied his Lord (Luke 22:54–62).

When Matthew 16:18–19 is considered alongside the key in this painting, new thoughts are provoked about Christ, Peter, and the kingdom of heaven. This still life does not answer any questions about this passage. It is the visual equivalent of Christ’s command to the disciples ‘not to tell anyone about Him’ (Matthew 16:20; Mark 8:30; Luke 9:21). The openness and ambiguity of the painting only provokes more questions. And perhaps the questions provoked in us recall in turn the questions that the disciples must have had, but did not ask.

Raphael

Christ's Charge to Peter, cartoon for a tapestry, 1515–16, Bodycolour (glue tempera) on paper mounted on canvas in the late 17th century, 344 x 534 cm, The Royal Collection Trust, On long-term loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; ROYAL LOANS.3, ©️ Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Courtesy Royal Collection Trust / His Majesty King Charles III 2024

Keys to Jealousy?

Commentary by Roald Dijkstra

In Matthew 16:18–19, the Apostle Peter receives an extraordinary honour: Christ promises him the keys to the kingdom of heaven. John 21:15–17 also exalts Peter: Christ entrusts his flock to his disciple.

In his cartoon for a tapestry made to be hung in the papal Sistine chapel, Raphael includes references to both of these passages. Part of a series of tapestries featuring the Acts of the Apostles, the Petrine episodes (like this one) were especially appropriate choices for Peter’s successor in the See of Rome.

The result is striking: Jesus, standing at left, points with his right arm to a flock of sheep and with his left to a key in the hands of the kneeling figure of Peter. Nothing in normal daily life relates the two: who needs a key to pasture his flocks? Precisely this incongruity makes Raphael’s intentions abundantly clear.

Christ and Peter look at each other, as if in private conversation. But they are not alone. In fact, the other disciples occupy the largest part of this composition. There are ten of them (as would have been the situation in John 21, following Judas’s death). They don’t look happy: the young man in red and green at the front (identifiable as John, the Beloved Disciple, based on a later cartoon) seems to beg for the same honour as Peter. The gesture of apparent resistance made by Andrew, the disciple at John’s right, may well convey the opinion of the other disciples. In the Bible, nothing is said about the disciples’ response to Peter’s honour, but some other passages suggest that they quarrelled about their position (Luke 9:46).

In the background we see a city. It could have been a reference to the kingdom of heaven, if it were not on fire: a symbol of the jealousy of men around people with a special mission?

The sheep at the left of the composition recall how, in the Gospel of John, Christ’s flock is entrusted to Peter three times (vv.15–17): the honour therefore also poignantly reminded him of his threefold denial. An equally poignant moment came after the deliverance of the keys, when Christ calls Peter ‘Satan’ and a ‘stumbling block’ (Matthew 16:23). Was it to mitigate the jealousy of the disciples that Jesus reprimanded Peter?

References

Evans, Mark & Anna Maria De Strobel. 2010. ‘Christ’s Charge to Peter’, in Raphael. Cartoons and Tapestries for the Sistine Chapel, ed. by Mark Evans and Clare Browne, with Arnold Nesselrath (London: V&A Publishing), pp. 74–81

Unknown artist

Traditio Clavium Mosaic, mid-4th century, Mosaic, Mausoleo di Santa Costanza, Rome; Independent Picture Service / Alamy Stock Photo

Keys and the Law

Commentary by Roald Dijkstra

It was probably around the year 350 that workmen finished a mausoleum for the daughter of Constantine, the first Christian emperor of Rome (306–37 CE). It was only in the thirteenth century that the mausoleum was transformed into a church.

Besides traditional, non-religious Roman imagery of a grape harvest, two explicitly Christian mosaics of the original decoration remain: this one depicting Peter and a seated Christ, and another of Christ between the Apostles Paul and Peter, in which He hands over a scroll to Peter with the text ‘the Lord gives peace’. This latter scene became common in early Christian art and is traditionally called Traditio legis (‘Deliverance of the Law’) or Dominus legem dat (‘The Lord gives the Law’). It is the reflection of the new position of Christianity as a religion related to the mighty men of this world, which started with the conversion of the Constantinian house.

The former scene is what we see here. Looking at the mosaic today, it is not clear what Peter receives: is it the keys or the Law? Both scenes existed in early Christian art, though—if it is keys—this is the earliest example of such an image. The object that is being handed over has been ambiguously restored and now appears as an unidentifiable triangular form.

In any case, the mosaic seems to be a variant of the Traditio legis scene: Christ is portrayed majestically on a globe. We are not on earth anymore—an impression that is confirmed by the palm trees, which symbolize heaven. This would suggest that the mosaic shows the deliverance of the Law. But Christ already holds its traditional symbol, a scroll, in his left hand: does this scroll then contain something else? On the other hand, if he is handing over the keys, where are the other apostles?

The mosaic may help us in rethinking the biblical passage: what do the keys of the kingdom of heaven actually mean? By leaving the object unidentifiable the restorer may have, inadvertently, made the best possible choice.

References

Dijkstra, Roald. 2018. ‘Imagining the Entrance to the Afterlife. Peter as the Gatekeeper of Heaven in Early Christianity’, in Sacred Thresholds. The Door to the Sanctuary in Late Antiquity, ed. by Emily van Opstall (Leiden: Brill), pp. 187–218

Noga-Banai, Galit. 2015. ‘Dominus legem dat: Von der Tempelbeute zur römischen Bildinvention’, Römische Quartalschrift für christliche Altertumskunde und Kirchengeschichte, 110: 157–74

Rasch, Jürgen J., and Achim Arbeiter. 2007. Das Mausoleum der Constantina in Rom (Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern)

Mario Tozzi :

Still life with a key, 1938 , Oil on canvas

Raphael :

Christ's Charge to Peter, cartoon for a tapestry, 1515–16 , Bodycolour (glue tempera) on paper mounted on canvas in the late 17th century

Unknown artist :

Traditio Clavium Mosaic, mid-4th century , Mosaic

Keys to Understanding

Comparative commentary by Roald Dijkstra

The Gospels are full of mysteries. One of the more obscure passages, however, is the promise of Christ to Peter in Matthew 16:18–19. We find it only there.

Peter was the leader of the apostles. Christ himself gave him a new, symbolic name in Aramaic to accompany Simon, his Jewish name: ‘Kefas’, which is Petros, ‘rock’, in Greek.

In Matthew 16 uniquely, Christ bestows an enigmatic honour on Peter: he will receive the keys of the kingdom of heaven. Peter’s special position is emphasized again in John 21:15–17, when Christ entrusts his flock to Peter.

These passages have a long history of interpretation. Since Peter was the rock of the Church and his martyrdom occurred in Rome (as narrated for the first time in the apocryphal Acts of Peter at the end of the second century), Roman bishops claimed that Rome’s church had a status which surpassed that of the other churches.

Visualizations of Matthew 16, and of verses 18–19 in particular, have always been full of political meaning. In a cycle of paintings of Peter’s life, they do not occur accidentally. It is unthinkable that Raphael would omit this event in his design for the tapestries of the Sistine Chapel. The artist was perfectly aware of Peter’s importance: he even contributed as an architect to the new St Peter’s Basilica in Rome (1506–1626), which replaced the one built under the emperor Constantine in the fourth century. It was not a coincidence either, therefore, that Constantine’s daughter Constantina included a mosaic based on this passage in her mausoleum. Several scholars have suggested that the image she used was inspired by an apse mosaic in old Saint Peter’s (see, e.g., Brandenburg 2017: 55–56).

The deliverance of the keys to Peter happens in two distinct domains: the event in the Gospel happened on earth, in the district of Caesarea Philippi (Matthew 16:13), the other is anticipated in heaven. It was in the former place that Jesus asked his disciples who the people said he was and what the disciples themselves thought of it (Matthew 16:13–16; Mark 8:27–30; Luke 9:18–22). In this place, Jesus reprimanded Peter, because he criticized divine intentions (Matthew 16:21–23; Mark 8:31–33). Just as this divine plan had consequences on earth as well as beyond, Peter’s keys gave him prestige on earth (placing the apostle in a long tradition of religious key-bearers) and a special position in heaven.

It is difficult to pin down what exactly happens in Matthew 16:18–19. Raphael chose a direct interpretation, fitting for a cycle of Peter’s life, but combined it with a scene based on John 21:15–17 in order to strengthen his message. His painting situates the deliverance of the keys—as often, only one key is visible—in an earthly, almost bucolic landscape. (It is only on closer inspection that the city in the background is found to be on fire.)

The anonymous mosaicist of the Santa Costanza chose a realm in another world. The palm trees were one of the symbols of heaven in early Christian art. There is no threat; nothing disquieting shows itself. Christ is no longer earth-bound, but ascended, and enthroned in heaven. He does not have the earth as his footstool (Isaiah 66:1 and elsewhere), but as his throne.

In Mario Tozzi’s still life, all narrative aspects have disappeared. Clearly, this painting was never meant to reflect our passage, contrary to that of the ancient mosaicist or Raphael. And yet, it may raise the most questions about the biblical text. The rock in the painting is ‘loosed’ (Matthew 16:19), yet the key is at the centre; the Passion and Resurrection are near (the cup, as a symbol of Christ’s suffering and the coming Kingdom; Matthew 26:29, is shown on the left). This provokes the question what the real key to the kingdom of heaven is. Access to heaven and the power to be freed on earth: are they the key to what faith is?

The rock is certainly not an unambiguous symbol. Is it the rock of Christ’s teaching upon which a wise man builds his house (Matthew 7:24)? Or is the rock God Himself (Psalm 62:3, 7, 8)? Or maybe Peter and the apostolic tradition (Matthew 16:18)?

What is the key to the biblical passage? Do these works of art help? They surely do not give a definitive answer. They offer different perspectives. By doing so, they can guide the questions we may have after reading: the place to which they guide us remains unknown. At least we have some keys.

References

Brandenburg, Hugo. 2017. Die konstantinische Petersbasilika am Vatikan in Rom. Anmerkungen zu ihrer Chronologie, Architektur und Ausstattung (Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner)

Dijkstra, Roald (ed.). 2020. The Early Reception and Appropriation of the Apostle Peter (60–800 CE): The Anchors of the Fisherman (Leiden: Brill)

Karatas, Aynur-Michèle-Sara. 2019. ‘Key-bearers of Greek Temples: The Temple Key as a Symbol of Priestly Authority’, Mythos 13, http://journals.openedition.org/mythos/1219 [accessed 9 February 2024]

McKitterick, Rosamund et al. (eds.). 2014. Old Saint Peter’s, Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Lumpe, Adolf, and Hans Bietenhard. 1991. ‘Himmel’, in Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum. Band XV: Hibernia–Hoffnung, ed. by Ernst Dassmann (Stuttgart: Anton Hiersemann), pp. 173–212

Commentaries by Roald Dijkstra