Matthew 27:1–10

The Death of Judas

Unknown artist, Rome

Casket, also known as the Maskell Passion Ivories, 420–30 CE, Ivory, Each panel approx. 7.5 x 9.8 cm, The British Museum, London; 1856.06-23.4-7, © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

‘Blood Money’

Commentary by Joanna Collicutt

This is one of the earliest surviving depictions of the crucifixion, part of a series of four plaques portraying the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Jesus. It is remarkable, if not unique, in the history of Christian art, because it juxtaposes the deaths of Jesus and Judas, offering the two figures to the viewer as a pair, and reminding us that Matthew’s Gospel indicates that they died on the same day.

The contrast between the two is striking. Jesus is not the pathetic dead or dying ‘man of sorrows’ of Isaiah 53, but very much alive, even perhaps smiling, standing erect with eyes and arms wide open as if to welcome all comers. As in John’s Passion narrative, Jesus is surrounded by the figures of his mother, the beloved disciple, and a Roman soldier (known in later tradition as Longinus) who inserts a spear into his side. The presentation of Judas draws on Matthew 27, with the discarded pieces of silver clearly visible at his feet. Unlike Jesus, he is lifeless, limp, and, crucially, alone, outside the social circle on the right.

Yet Judas and Jesus are not cut off from each other; Jesus’s right hand reaches above the heads of his loved ones towards the tree on which Judas hangs. There is an interplay between the dead wood of the cross and the living tree which forms Judas’s gibbet, which, like the mustard tree of Jesus’s parable, welcomes the birds of the air to make nests in its branches (Matthew 13:32). The interconnectedness of the composition communicates the sense that Judas too has his place in the scheme of salvation.

Jesus is pierced and blood issues from his wounds; Judas is expelled to undergo a bloodless solitary death. There are strong echoes here of the pair of goats from the Day of Atonement: one a sin offering for the LORD whose blood cleanses the people, the other sent away to ‘bear all their iniquities upon him to a solitary land’ (Leviticus 16:22).

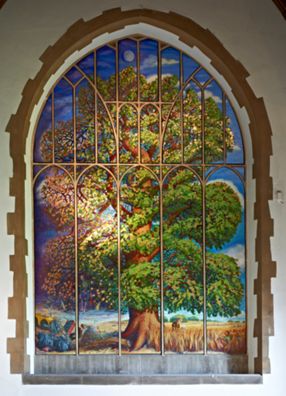

Mark Cazalet

Tree of Life, 2014, Oil on oak panel, 3.5 x 6 m [approx.], Chelmsford Cathedral; © Mark Cazalet / Chelmsford Cathedral / Bridgeman Images; Photo: Courtesy of the Chelmsford Cathedral

‘He Repented’

Commentary by Joanna Collicutt

Here is a massive Gospel oak dying on one side and flourishing on the other. The work was commissioned as an ‘eco monument’ by Chelmsford City Council and is sited in Chelmsford Cathedral. Its aim is to confront the viewer with the fruits of the Industrial West’s exploitation of the planet and its people, signified by the landfill site in the lower left corner, on the tree’s dying side. In contrast, on the flourishing side, is a scene of rural peace and plenty, occupied by St Cedd reading passages from the Gospel in the shade of the oak. His mission to this part of England in the seventh century is re-presented as part of the redemption of the land.

The surface question posed by the work is ‘can death be transformed to life?’; the deeper question is ‘can humanity be redeemed?’. These are focused on the fate of one individual: Judas. The dead body of Judas hangs from the lower dying branches, his discarded silver tumbling into the landfill, as if to say, ‘This is where the love of money has got us’. But in the upper, living branches, populated by birds and butterflies, we find Judas resurrected, eagerly climbing higher and higher, fortified on his journey with a thermos and sandwiches.

For the artist, Mark Cazalet, Judas is ‘everyman’. Similarly, the analytic psychologist Carl Jung understood Judas’s story as signifying humanity’s shadow-side: ‘the expression of a psychological fact, that envy does not allow humanity to sleep, and that all of us carry, in a hidden recess of our heart, a deadly wish towards the hero’ (1922: 38–39). Indeed, Matthew’s account of the Last Supper indicates an awareness among the Twelve that any of them could have been the betrayer (26:22).

On this reading, if Judas is not redeemable then nobody is redeemable; if Judas is redeemed then there is hope. Matthew’s detailed description of Judas’s repentance opens the door to this redemption. It presents Judas as feeling remorse (metamelomai; v.3), acknowledging guilt, and, in throwing down the pieces of silver, ritually re-enacting a noble prophetic action (Zechariah 11:13). This is an upward trajectory from death to life, interrupted but not necessarily ended by suicide.

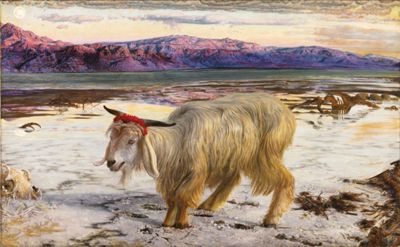

William Holman Hunt

The Scapegoat, 1854–56, Oil on canvas, 86 x 140 cm, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight; LL 3623, Bridgeman Images

‘He departed; and he went and hanged himself’

Commentary by Joanna Collicutt

When this painting was first exhibited in 1856 at the Royal Academy the response was mixed. Viewers appreciated the vivid and detailed depiction of the area of “Oosdoom” (Kharbet Usdum) by the Dead Sea—an inaccessible and inhospitable place of which no photographs yet existed—and the courage and endurance of the artist in exposing himself to multiple hazards there in order to paint the work ‘from life’.

There was much less appreciation of the typological symbolism employed. This was set out in very full programme notes presenting the Azazel (scapegoat) of the Day of Atonement ritual in Leviticus 16 as a type of Christ, with the text on the frame clearly linking the two figures via the ‘suffering servant’ of Isaiah 53.

Hunt’s goat, like Isaiah’s suffering servant, is full of pathos, cut off from the land of the living, spent, and near to death, thus evoking a Christ who ‘was despised and rejected’. He bears away the people’s sins signified by his scarlet headband (Isaiah 1:18), a symbol Hunt would apply directly to the figure of Christ in a later painting, The Shadow of Death. The outcome is atonement and new life, hinted at by the olive branch in the left foreground.

Yet neither public nor critics found the symbolism persuasive, and Hunt himself reflected in hindsight, ‘I had over-counted on the picture’s intelligibility’ (Hunt 1905: 108; Bronkhust 2006). It was certainly unprecedented in its iconography. More importantly, the New Testament does not exploit this christological type, and the history of textual commentators attempting to do so has been fraught with theological problems (Lyonnet & Sabourin 1970).

Recent biblical scholarship has instead begun to explore the way Christ and the scapegoat figure appear as a pair in the Gospel narratives. In this vein, some have noted connections between the scapegoat and Barabbas evident in Matthew 27:16ff (Moscicke 2018). Others (e.g. Anstis: 2012) have pursued a more intriguing possibility offered by the events earlier in that chapter where Judas, doomed to carry blame throughout history, is dismissed from the Temple to face his demons alone in the social wilderness.

References

Anstis, Debra. (2012). ‘Sacred Men and Sacred Goats: Mimetic Theory in Levitical and Passion Intertext’, in Violence, Desire and the Sacred: Girard’s Mimetic Theory Across the Disciplines, vol. 1, ed. by Scott Cowdell, Chris Fleming & Joel Hodge (New York: Continuum), pp. 50–65

Bronkhurst, Judith. (2006). William Holman Hunt: A catalogue raisonné (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press)

Hunt, William Holman. (1905). Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, vol. 2 (London: Macmillan & Co.)

Lyonnet, Stanislas and Leopold Sabourin. (1970). Sin, Redemption, and Sacrifice: A Biblical and Patristic Study, Analecta Biblica 48 (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Commission)

Moscicke, Hans. (2018). ‘Jesus as Goat of the Day of Atonement in Recent Synoptic Gospels Research’, Currents in Biblical Research 17.1: 59–85

Unknown artist, Rome :

Casket, also known as the Maskell Passion Ivories, 420–30 CE , Ivory

Mark Cazalet :

Tree of Life, 2014 , Oil on oak panel

William Holman Hunt :

The Scapegoat, 1854–56 , Oil on canvas

Scapegoating, Splitting, and the Tree of Life

Comparative commentary by Joanna Collicutt

The story of Judas evokes complex feelings and questions, among these a desire for its resolution in redemption for him and thus for all in desperate situations. The rich and interconnected visual symbolism of these three works points to a similar network of types and symbols in the biblical text, revealing afresh its capacity to speak into these human complexities.

The Gospels primarily draw on the Exodus story to interpret the sacrifice of Christ, referring to both the Passover (Exodus 12) and the sealing of the Sinai covenant (Exodus 24). The Epistles go wider, drawing on imagery from the Day of Atonement, presenting Christ as either the sin offering, the high priest who slaughters it, or both. The blood of the sin offering cleanses the people and gives them access to the living God (Hebrews 9:13–14) and its remains are left ‘outside the camp’ (Leviticus 16:27; Hebrews 13:11,13).

The location of Jesus ‘outside the camp’, expelled to die beyond the city limits ‘for the people’ (John 11:50), has been understood by René Girard (1977) as an expression of ‘scapegoating’. Girard’s concept of scapegoating is actually a long way from the original scapegoat ritual (Douglas 2007), and Christ is not the antitype of the Azazel (hence the exegetical challenge of Hunt’s painting). Nevertheless, Girard is surely correct in identifying the psychosocial scapegoating of Jesus as a key aspect of the Gospel accounts, and it has consequently received much fruitful scholarly attention.

In comparison, the scapegoating of Judas has been relatively neglected. While the narrated events scapegoat Jesus, the narratives of the Gospel writers scapegoat Judas (Anstis 2010: 57). This is most evident in the Gospel of John’s descriptions of Judas as a thief (12:6) and unclean (13:10–11), and his marking of Judas’s departure by nightfall (v.30). In the narrated chronology, Judas is not revealed as the betrayer until shortly before his cataclysmic action, but in three of the Gospel narratives this is signalled from his first appearance. The narratives manage the troubling awareness that the betrayer could be any of the Twelve by cathartic relief first through the clear identification and then the violent expulsion of the betrayer from the group. Jung reads this as a form of psychic splitting in which the dark side of the community’s soul is first isolated, then radically separated from it (2009: 71).

Splitting is not inherently bad, but is only a temporary holding strategy in the face of intolerable psychic conflict. For growth to occur the darkness has to be integrated; it must eventually be incorporated into the story, not expunged from it. There are, moreover, signs of such integration at work in the Gospel narratives. The assertions that Judas had been fore-chosen as the betrayer despite only being revealed as such at the last minute (Matthew 26:24 and parallels) place him within the scope of God’s plan. Similarly, Jesus’s foreknowledge of Judas is presented as more than passive; it seems ‘that Jesus actively promotes his own betrayal and designates Judas as its agent’ (Maccoby 1992: 64). Matthew adds a human dimension, recounting Judas’s remorse (27:3) and emphasizing, if ironically, his ‘friendship’ with Jesus (26:50), thus alluding to the psalmist’s lament of betrayal by a companion (Psalms 49 & 51). The intimacy between the two men is expressed by the closeness of their hands in the bread bowl (Matthew 26:23 and parallels; Psalm 41:9), and perhaps recalled in Jesus’s outstretched hand in the Maskell Ivory.

Like the two Yôm Kippur goats, these two figures should be treated as an integral pair, each in his own way scapegoated, each having a place in the divine economy of salvation but also in communicating its profound life-giving reality. It is here that the tree of life motif becomes significant. This archetypal symbol is present in all three works in this exhibition.

Hunt’s use of the tree motif is subtle. The olive branch in the painting is paired with a branch carried by Noah’s dove that is adjacent to it on the frame (designed by Hunt but not shown here). It is also redolent of the Jesse tree of Isaiah 11. These powerful symbols of hope were intended to convey ambiguity as to the goat’s ultimate fate (Hunt 1856).

The other two works shown here directly link the life-giving tree with Judas. Mark Cazalet’s The Tree of Life presents it as an opportunity for new beginnings, as both sign and means of transformation. The Christ of the Maskell Ivory seems to bring his friend’s tree-gibbet to life through his touch. Here transformation and integration go hand in hand.

References

Anstis, Debra. (2010). ‘A Typological Pair: The Yom Kippur and Passion Texts Based on Girardian Mimetic Theory’, University of Auckland, Unpublished Masters Thesis

Douglas, Mary. (2007). Jacob’s Tears: The Priestly Work of Reconciliation (New York: Oxford University Press)

Girard, René. (1977). Violence and the Sacred (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press)

Hunt, William Holman. (1856). ‘Letter to Thomas Miller 31 March’

Jung, C.G. (2009). Liber Novus / The Red Book, trans. by M. Kyburz, J. Peck, & S. Shamdasani (New York: Norton)

Maccoby, Hyam. (1992). Judas Iscariot and the Myth of Jewish Evil (New York: Free Press)

Commentaries by Joanna Collicutt