Philippians 2:1–11

The Christ Hymn

Works of art by Vincent van Gogh, William Holman Hunt and Unknown English artist, Central [Oxford and St Albans]

Unknown English artist, Central [Oxford and St Albans]

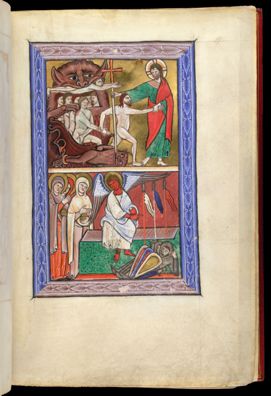

The Harrowing of Hell, from Arundel 157, fol. 11r, c.1220–40, Ink, tempera, and gold leaf on vellum, 295 x 200 mm, The British Library, London; Arundel 157, fol. 11r, © The British Library Board

Under the Earth

Commentary by Joanna Collicutt

The Harrowing of Hell (the idea that on Holy Saturday Christ went down into Hades to retrieve the souls of the righteous who had predeceased him) is a post-biblical development of Christian thought, but its origins lie in the New Testament. Matthew 12:40 and Ephesians 4:9 assert Jesus’s descent to the depths, and 1 Peter 3:19 talks of his proclaiming the gospel to imprisoned spirits, both righteous and unrighteous, after his death.

The Philippians ‘hymn’ (2:6–11), thought by many to be a pre-Pauline liturgical text pressed into service by the Apostle, has this sense of descent in its first two verses; there is also a reference to the depths of the earth in verse 10. But the overall trajectory is clearly down and then up, from degradation to exaltation, with the turning point at verse 9.

And why has Paul pressed this hymn into the service of his argument on faithful Christian living? He wants his readers to understand that there is no route to exaltation other than to be ‘in Christ’, to participate in his humility and obedience unto death (Philippians 3:6–14). Christ descended to be with human beings and to offer them the opportunity of being taken hold of by him (the literal translation of 3:14) through faith, so that he could as it were pull them up with him into the resurrection life.

This miniature from the introduction to an English Book of Psalms, communicates this movement superbly, capturing the liberating hold of Christ on Adam (with Eve not far behind), their re-birth from the rather charming Gruffalo-like jaws of hell to the attainment of full human dignity, and the transformation of despair to joy on the faces of those about to be released. Christ is seen to have triumphed over the powers of darkness and, unequivocally to have done this via his cross (Philippians 2:8).

This particular take on the traditional iconography of Christ at the mouth of Hades boldly asserts that there is no such thing as a God-forsaken place or human condition. This is an image steeped in hope.

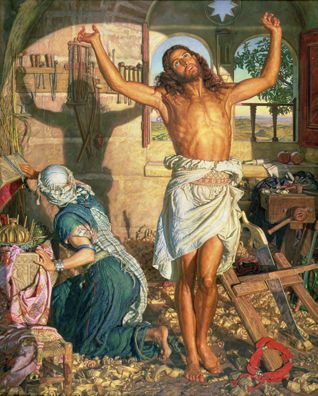

William Holman Hunt

The Shadow of Death, 1870–73, Oil on canvas, 214.2 x 168.2 cm, Manchester Art Gallery; 1883.21, Manchester Art Gallery, UK / Bridgeman Images

‘Being Found in Human Form’

Commentary by Joanna Collicutt

William Holman Hunt’s The Shadow of Death is ambitious in scale, technical execution, and theology. As with many of Hunt’s paintings, the viewer is at first almost overwhelmed by the density of detail, the vivid and iridescent hues, and the sheer number of symbolic references. It is difficult for the eye to come to rest and it is difficult to identify the ‘real’ subject of the painting. It could be a purely human incident, a young carpenter stretching, stiff from his labours, as the day draws to its close. But we are also offered here a glimpse of the redemptive work of Christ. In ‘rendering the simple and real allusive’ the painting not only points to Christ’s work but exemplifies Christ’s own artistry (Sund 1988: 668).

At first glance the painting seems to be about the crucifixion (and the title demands this reading). The evening sunshine that so gloriously transfigures Jesus’s body and intensifies the blue of his natural halo also casts a dark shadow. For this moment the carpenter’s tools prefigure the instruments of the passion; the luxurious and pleasurable extension of tired limbs prefigures their brutal distortion on the cross.

Yet Hunt had painted a very similar (smaller) version a year earlier and inscribed Philippians 2:7–8 on the frame of his own design, thus drawing attention to the humanity and humility of the scene rather than its ominous signs of violence. Christ is ‘found in the form’ of an ordinary Jewish artisan standing in the detritus of a humble workshop, a space he shares with his mother. She has opened a chest whose treasured contents, gifts from the Magi, point back to the nativity as much as forward to the cross.

The ‘real’ subject of the painting is the relationship between incarnation and humility (v.6). It’s a portrait of a flesh-and-blood (laboriously researched) ‘real’ historical Jesus, whose humility is expressed first in the ambiguous circumstances of his conception and birth and then in his lowly status as a working man. These in themselves foreshadow the nature of his death by the most humiliating execution his culture could contrive.

Vincent van Gogh

The Bearers of the Burden (Miner's Wives Carrying Sacks), 1881, Pen in brown and black ink, white and grey opaque watercolour, on [originally] blue laid paper, 47.5 x 60 cm, Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands; KM 122.865 recto, World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

‘Have This Mind’

Commentary by Joanna Collicutt

In this passage Paul urges his readers to cultivate humility and exhorts them to take Christ as their model.

Vincent van Gogh has been described as displaying a ‘passionate identification with Christ’ throughout his life (Pritchard 1971: 15), but most intensely in the years immediately preceding his emergence as an artist. Having undertaken theological studies, he was appointed as a lay pastor in the impoverished mining district of Borinage in Belgium in 1879. Van Gogh was obsessed with following Christ in his solidarity with those who serve, and for some months lived in a miner’s hut, not counting entitlement to the pastor’s lodgings ‘a thing to be grasped’ (Philippians 2:6). He even went down into the dangerous Marcasse mine. Later he would describe this as ‘the depth of the abyss’ (Van Gogh 1978: 200). Like Christ, he had descended. Not long after, having been dismissed from his position, he again modelled himself on Christ: ‘I shall rise again: I will take up my pencil…’ (Van Gogh 1978: 136). Here we see the result.

As in so many societies, the labour of women involves transporting heavy loads (children, water, crops). Here they are bent double under sacks of coal gleaned from slag-heaps to burn in their homes. The simple documentation of their work can be seen as a redemptive artistic action expressing Van Gogh’s continuing aspiration to the mind of Christ.

But there is more; the original English title almost certainly alludes to Matthew 23:4 where Jesus denounces the religious leaders for laying heavy burdens on ordinary people. The viaduct in the distance is a triumphant monument to the industry that determines the lives of the women. Behind it, separated from their world of servitude but benefiting from it, stand a Protestant and a Catholic church; these women are at once abandoned and oppressed by the hypocrisy of institutional religion.

This, we are reminded, was also true of Christ Jesus, for hanging in the right foreground we see him who ‘became obedient unto death … on a cross’ (Philippians 2:8), bearing the burden of the world, in deep solidarity with suffering humanity.

References

Pritchard, Ronald E. 1971. D.H. Lawrence: Body of Darkness (London: Hutchinson)

Sund, Judy. 1988. ‘The Sower and the Sheaf: Biblical Metaphor in the Art of Vincent van Gogh’, The Art Bulletin, 70.4: 660–676

Van Gogh, Vincent. 1978. The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh (Boston: New York Graphic Society)

Unknown English artist, Central [Oxford and St Albans] :

The Harrowing of Hell, from Arundel 157, fol. 11r, c.1220–40 , Ink, tempera, and gold leaf on vellum

William Holman Hunt :

The Shadow of Death, 1870–73 , Oil on canvas

Vincent van Gogh :

The Bearers of the Burden (Miner's Wives Carrying Sacks), 1881 , Pen in brown and black ink, white and grey opaque watercolour, on [originally] blue laid paper

Work, Word, and the Cross

Comparative commentary by Joanna Collicutt

This exhibition’s three artworks can help us to move through the text of Philippians 2:1–11, exploring the nature of Christ’s setting aside of entitlement, his taking on humble human form, his obedience to a shameful death, and the transformation of that death to exaltation and triumph for the whole human race.

All are concerned with the work of Christ and each engages deeply with the reality of labour. Both William Holman Hunt and Vincent van Gogh are concerned to validate and indeed dignify the physical toil of the ‘working man’. Both of them put huge effort into these particular works. Hunt and his models had to endure extreme heat and cold as he painted The Shadow of Death outside Bethlehem, difficulties described by George Landow as ‘themselves … part of the devotional importance of his work’ (1972: 206). Van Gogh is said to have ‘foregrounded rather than disguised the artistic labour required to generate his pictures’ (Walker 1981: 50). Both sought to have the mind of Christ Jesus (Philippians 2:5) through the labour of painting and, like the incarnate Christ of John 1:14, through inhabiting the context depicted (Hunt in the Holy Land, Van Gogh in Belgian and Dutch mining communities). Moreover, Van Gogh identified strongly with what he took to be Christ’s self-emptying (Philippians 2:7), habitually displaying what has been called ‘a psychological compulsion to self-abasement’ (Stewart 1991: 104).

Work is also a feature of ‘Hand B’ whose personal story is unknown but who would have been part of a religious community for whom the laborare (work) of manuscript illumination was inherently orare (prayer). Furthermore there is a reflection on the work of Christ in the miniature. The Harrowing of Hell scene is one half of a double miniature, itself part of a series of two-scene images in the Psalter that tell the story of Christ. Its other half is ‘The Holy Women at the Tomb’. It is a reminder to those who might think that Jesus was resting in the tomb on Holy Saturday that he was in fact about his work. The Holy Women were just not in a position to see it (Mark 4:26–27).

All three images have a concern with incarnation, the enfleshment of the Word in an artistic material medium. For Hunt, archaeological and ethnographic accuracy in the depiction of the human Jesus is designed to make him more real (Giebelhausen 2006). For Van Gogh, art is about the communication of spiritual truth freed from conventional religious forms and located in the lives of real people. Hand B creates an image to draw the meaning of the Psalms into the history of Jesus.

For each artist the image is inseparable from the Word. Hunt was in the habit of inscribing the frames of his religious paintings with a biblical text, a practice that has been identified as ‘explanatory rhetoric’ (Rowe 2005), usually eschewing further explanation and offering the inscription as an open hermeneutic invitation. Van Gogh wrote many letters to his brother, probably intended for wider readership, describing the envisioning and execution of his pictures and his response to the finished products. These act as a kind of apologia, and often enhance the experience of looking at the image in question. The nature of Hand B’s undertaking is both literally and figuratively to shed light on the sacred text. The verbal word and the material word are thus interconnected in these works.

Above all, these three images engage with the cross. This goes without saying in The Shadow of Death, but the crucifix is also prominent in The Bearers of the Burden where its lightness (which the darkness cannot overcome; John 1:5) contrasts so markedly with the gloom of the women’s surroundings.

Yet it is in the Harrowing of Hell that the cross has the most central place, dividing the composition in two, just as it does in the Philippians hymn. Here we see that it is the cross of Christ’s staff that beats down Satan and the powers of darkness; the cross that offers human beings comfort (Psalm 23:4) and healing (John 12:32).

The cross is the pivot of the work of salvation. This is why the degradation and victory of the cross are held together by ‘therefore’ rather than split by ‘but’ in verse 9. The cross is at once the culmination of Christ’s coming humbly to dwell in solidarity with his people in their powerlessness and suffering; the natural consequence of his humble life of radically subversive goodness; and the means by which he raises up humanity with him to the heavenly places.

References

Coombs, James H., et al. 1986. A Pre-Raphaelite Friendship: The Correspondence of William Holman Hunt and John Lucas Tupper (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press)

Giebelhausen, Michaela. 2006. Painting the Bible: Representation and Belief in Mid-Victorian Britain (Aldershot: Ashgate)

Landow, George. 1972. ‘William Holman Hunt’s “The Shadow of Death”’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 55.1: 197–239

Pritchard, Ronald E. 1971. D.H. Lawrence: Body of Darkness (London: Hutchinson)

Rowe, Karen D. 2005. ‘Painted Sermons: Explanatory Rhetoric and William Holman Hunt’s Inscribed Frames’ (PhD diss., Bowling Green State University)

Stewart, Jack. 1991. ‘Primordial Affinities: Lawrence, Van Gogh and the Miners’, Mosaic, 24.1: 93–113

Walker, John. 1981. Van Gogh Studies: Five Critical Essays (London: Jaw)

Commentaries by Joanna Collicutt