John 12:20–36

Losing Life and Finding Life

Brett a'Court

Manu-Kahu, 2007, Oil on canvas, Private Collection; © Brett a'Court

Christ on High

Commentary by Rod Pattenden

This striking image of an airborne Christ is by New Zealand painter Brett A’Court. It is part of his visual research into how to bring together the spiritual insights of the indigenous culture of the Maori people and those of Christianity.

In cultural terms it is a hybrid image, something that occurs when two cultures are in a process of mutual re-assessment. It is an exploration that has the potential to be offensive to either culture, but one that also carries the potential for new forms to arise that express the insights of both traditions.

Such imagery also responds to the colonial suppression of local cultures, allowing for innovations to arise from outside the usual orthodox channels. A Christ figure flying in the sky like a kite is such a form. It is a new thing, a potential aberration, but one full of potential for new insight.

The ‘Manu-Kahu’ in Maori culture refers to the Harrier Hawk, a bird considered to provide a spiritual connection to the divine. It also refers to the Maori cultural practice of making kites, which is a common recreational practice but has traditional religious meaning. Historically, massive kites were produced for significant ritual occasions. These could carry the weight of a human person, and in their ritual role were flown with up to a kilometre of rope to command vast terrains. These kites were considered in Maori beliefs to access the supernatural life force associated with animals, birds, and the dream of flight. For the artist, this provides an appropriate connection to a Christ figure who 'holds' the land with benevolence and grace.

This new and surprising iconography dislodges any colonial mentality that considers a European way of seeing things to be the only authoritative one. A’Court’s is a thoroughly contextual Christ for New Zealand, the land where birds have become the dominant species. Here we do not encounter an introduced species, carrying a foreign spirituality. This is Christ at home in the physical landscape of the Pacific.

For viewers in other contexts, it serves to expand our sense of encounter with a God at home in the world, an incarnation that honours the material world we inhabit, and that raises up the viewer’s gaze towards a spiritual horizon.

And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself. (John 12:32)

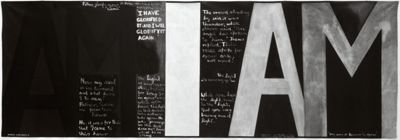

Colin McCahon

Victory Over Death 2, 1970, Synthetic polymer paint on unstretched canvas, 207.5 x 597.7 cm, The National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; Gift of the New Zealand Government 1978, NGA 79.1436, © Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust; Gift of the New Zealand Government 1978 / Bridgeman Images

Faith and Doubt

Commentary by Rod Pattenden

This painting, overwhelming in scale, typifies Colin McCahon’s painterly struggle to explore the space between belief and doubt. It is a direct response to Jesus’s inner conflict as he faces death and questions how his life might glorify God.

McCahon is New Zealand’s most well-known artist, having garnered an international profile. He is admired for his painterly calligraphic style and handwritten texts. In his lifetime, he was an artist driven by a theological interest in visualizing faith and its absence. Through affirmations and negations McCahon explores the ultimate horizon of existence. He dares to explore the role of the artist as theologian.

The vast surface of the canvas is structured by the architecture of the divine affirmation; ‘I AM’. The ‘I’ appears like a crack of light that both illuminates the composition and breaks it in two. To the left there is a darkly shadowed ‘AM’ that emerges out of the darkness, turning the affirmation into a question. ‘AM I’? Like a delicate filigree the text of John 12:27–36 shivers through the in-between spaces, evidencing erasure and re-inscription. There is no final or definitive edit. We see all the changes, and the jostling of words as they compete for importance in conveying a clear meaning. There is no comfort here in finding a black and white declaration, but rather a moderated surface that evidences the history of questions and answers, affirmations and negations, faith and doubt.

Metaphorically speaking, this enormous text work teeters under the precarious weight of its construction. Here is the universal human search for understanding rendered in the only thing we have available: humble and fragile phrases. McCahon delineates the intense drama of this passage from John, by giving material and visual expression to the contrast between light and darkness, life and death, doubt and faith. Given its size (207.5 x 597.7 cm), there is an invitation for viewers to inhabit this space and to feel the weight and significance of each gesture as it forms itself into words, phrases, defining and redefining what we understand God to be, the ‘I AM’.

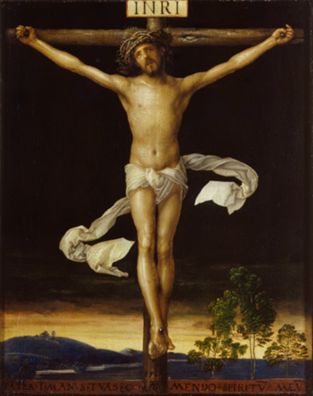

Albrecht Dürer

Christ on the Cross, 1506, Oil on linden wood panel, 20 x 16 cm, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden; Gal.-Nr. 1870, akg-images

Beholding Life and Death

Commentary by Rod Pattenden

In this small painting, Albrecht Dürer concentrates the attention of the viewer on the lone figure of Christ. There is no trace of the expected crowd of figures, including Mary his mother, Mary Magdalene, the disciples, and soldiers, all of whom are usually depicted in attendance at Christ’s crucifixion. It is as though they are absent, or we (raised up as Christ is) are seeing over their heads.

The viewer of this intimate work is drawn in to be the only witness, to contemplate and grasp the meaning of this harrowing death. The sky has darkened into a thick descending blackness that seems about to eclipse even the dimly rendered horizon. Hope has been extinguished. The space is compressed and claustrophobic. There is nowhere else to look except at this dying human form.

Yet in contrast to the downward fall of black sky there is a clear counterpoint. The depiction of the Christ figure also suggests, if only metaphorically, a turn upward. Christ’s eyes are raised towards the heavens, and the warm radiance reflecting from his body is luminous against the sky. In this enveloping cosmic darkness—high and lifted up—Christ is a light for the world.

We also notice the loincloths that surround his hips have responded to an awakening breeze. As Christ expels his last breath, it is as though there is at the same moment a sudden influx of air, which like the verdant trees behind, welcomes this wind of change—like when a grave is opened, and the stench of death is replaced by the fresh air of hope.

Dürer has created in this work a compressed and intensely personal space of contemplation that leaves viewers hovering in their imagination between life and death. The figure carries the physical signs of both. Even as Christ breathes his last on Good Friday, there is already a premonition of the rising life of Easter Sunday.

It is an intimate viewing experience, and yet the painting’s setting of a single central figure against a dramatic landscape anticipates the sublimity of the Romantic tradition. The Latin inscription along the bottom of the work—‘Father, into your hands I commend my spirit’—elides Christ’s journey to the dead with his journey to the Father. The contemplation of this process of death and life playing itself out in the body of Christ invites the viewer into that same journey.

Brett a'Court :

Manu-Kahu, 2007 , Oil on canvas

Colin McCahon :

Victory Over Death 2, 1970 , Synthetic polymer paint on unstretched canvas

Albrecht Dürer :

Christ on the Cross, 1506 , Oil on linden wood panel

Dying and Rising

Comparative commentary by Rod Pattenden

This sequence from John’s Gospel contains a range of extreme contrasts in emotion and intention. It takes us back and forth between death and life, through the inner struggles of Jesus and the revelation of God’s purpose.

John 11 begins with the raising of Lazarus, thus introducing John’s Passion narrative, which will include the plot by religious leaders to arrest Jesus, his anointing at Bethany, and his welcome into Jerusalem by the crowd as king.

Jesus then begins to talk about his death using the metaphor of a seed of wheat (12:24), and the now-familiar phrases of losing and finding one’s life (v.25). We are given an indication of Jesus’s inner turmoil and conflict as a voice from heaven thunders with an affirmation of glory (vv.27–28). We are then left with the image of Jesus being lifted up from the earth (v.32) and his encouragement to those listening to walk in the light (vv.35–36). Finally, Jesus slips from this public moment and ‘hides himself from them’ (v.36).

Colin McCahon’s large canvas is an attempt to enfold these contrasting perceptions and to play in and through the dark and light, the death and life, that structure this passage. It gives opportunity for the reader to fill out the visual elements of the story for themselves, and to inhabit an arena of tension and contrast. Rather than using the familiar nature of these verses as a source of comfort, McCahon wants us to explore the edges of uncertainty and be willing to live in the questions; to dismantle and explore faith as a form of discovery; to re-live the passage and its difficult horizons; and to acknowledge its echoes in our own lives. The work literally ‘spells out’ a space that is defined by both certainty and doubt. This visual habitation honours the positive aspects of questioning that allow a person to arrive at a new place of synthesis and resolution.

Albrecht Dürer’s lone crucified figure embodies the contrasting tensions of life and death, but here these marks are visually inscribed on the vulnerable flesh of Christ. This figure carries these physical signs and serves to embody the whole Easter narrative, from betrayal, to death, to burial, and finally to resurrection. Viewers are invited to take a devotional stance and enter the story as an act of contemplation, and in turn, to embody these signs of death and life in their own spiritual narrative. Dying and rising are the continuing cycle of experience for bodies who wait for redemption.

Brett A’Court’s flying Christ offers an innovative cross-cultural and ecological view of a Christ ‘lifted up’ (v.32) within the life of creation. Here is the divine presence pictured at a vantage point between heaven and earth, offering us a rope to hold on to so as to experience the exhilaration and hope found in the metaphor of flying. This is a figure who carries the wisdom of things being found in balance, in earth and sky, as well as in the wildness of land and the order of human culture. Rather than Christ being held aloft as a standard bearer of colonization or slavery, Christ is the one who invites vitality and harmony to be the mark of all earthly relationships. The meaning of Christ’s death moves beyond personal ethics, or even social relations, to include enemies, then other creatures, and finally the earth, as God’s gift.

In this complex narrative that begins Christ’s Passion, we are introduced to the larger themes that shape John’s theology of the cross as it moves towards glory, through the suffering figure of Christ intent on following God’s call. Of the four Gospels, it is above all John’s Gospel which invites the reader to contemplate and visualize the material signs of Jesus’s life and death. Jesus’s life is described in the tangible expression of the seven ‘I am’ sayings in the first half of the Gospel, where Jesus is described as bread (6:25ff.), light (8:12), vine (15:1), etc. The resurrection of Lazarus—a story found only in John—is also crafted to heighten our material and visual awareness. Jesus is delayed (11:6), we hear the emotion of Mary, Lazarus’s sister (v.33), Jesus is in turn moved to tears (v.35), and we arrive finally at the shuffling appearance of Lazarus as he comes out of the grave (v.44). The viewer understands the impact of these stories through the memory of the felt touch of the material things of ordinary life. It is into this ordinary world that God becomes flesh.

References

Bloem, Marja, and Martin Browne. 2002. Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith (Craig Potton Publishing and the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam)

Rosenblum, Robert. 1975. Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko (London: Thames and Hudson)

Tarlton, John. 1976/77. ‘Ancient Maori Kites’, Art New Zealand 3 [available at http://www.art-newzealand.com]

Commentaries by Rod Pattenden