Matthew 12:38–42; 16:1–12; Mark 8:11–21; Luke 11:29–32; 12:1, 54–56

The Sign of Jonah

Simeon Ardjishetsi

Baptism of Christ, from Gospel by the painter Simeon Ardjishetsi (Simeon of Arces), 1305, Manuscript illumination, The Matenadaran, Yerevan, Armenia; MS 2744, fol. 4r, Scala / Art Resource, NY

This is My Beloved Son

Commentary by Lauren Beversluis

In this manuscript illumination of the Baptism of Christ, Armenian artist Simeon Ardjishetsi (Simeon of Arces) uses bright colours, bold contrasts, and fantastical and ornamental details typical of the Vaspourakan school in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

St John the Baptist stands on a rectangular platform off to the left and leans over the figure of Christ, who is immersed in and partially visible through the blue and white waves of the Jordan River. Directly above Christ’s halo appears a dove, and to the right two angels fly downwards and reach towards him.

The scene is bordered by a rectangular frame and decorative ivy, as well as the hand of God, which reaches out of a cloud at the top, and at the bottom a coiled black sea creature, with jaws opened wide below Jesus’s feet.

In the Christian tradition, baptism is the rebirth into eternal life in Christ. The immersion in water is symbolic of death, and the resurfacing symbolizes rebirth. The water of life thus washes away sin and death. Old Testament figures such as Noah, Moses, and Jonah were often used to refer to and illustrate the significance of baptism through their stories of divine rescue from the devastation of the sea.

Likewise, in this illumination, Christ’s baptism is represented as a victory over a sea creature, symbolic of the devil, death, and/or hell. Jesus stands just above the creature, who lies upside down, mouth agape. With a twisting, serpent-like body and dragon-like head, it is highly reminiscent of the coiled sea creature spitting up Jonah so frequently depicted in early Christian art.

It is therefore possible that this image depicts Christ having been figuratively ‘swallowed’ before being ‘spat out’ in the symbolic death and new life of baptism. At the same time, the creature may allude to the vocal renunciation of the devil that catechumens undergo at baptism, or the more general victory over death that baptism accomplishes. In this case, the creature could be seen as not so much releasing Christ as being trampled by him, a subject with extensive biblical precedent (Psalms 74:13; 91:13; Isaiah 27:1; Job 41).

In either interpretation, this scene prefigures Christ’s own death and resurrection and is a potent evocation of the Sign of Jonah, by which Christ is understood to be the Son of God and the world’s Saviour.

References

Hakopian, Hravard (commentaries), V.H. Kazarian,and A.S. Matevossian (eds). 1978. ‘Simeon Ardjishetsi’, in Armenian Miniature: Vaspourakan [Madenataran, Mashtot's Institute of Old Manuscripts Under the Auspices of the Council of Ministers of the Armenian SSR] (Yeravan: Sovetakan Grogh)

Unknown artist, Italian school

Reliquary of Brescia (Brescia Casket or Lipsanoteca), front view, 4th century, Ivory casket, 22 x 32 x 25 cm, Museo di Santa Giulia, Brescia, Italy; Scala / Art Resource, NY

Waiting in the Belly of the Sea Monster

Commentary by Lauren Beversluis

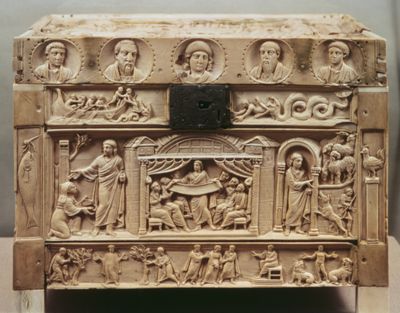

The Brescia Lipsanotheca (or Casket) is a small carved ivory relief with an internal walnut wood framework dating to the fourth century. Scholars are not certain of its original intended function, but most agree that it was probably a reliquary, and possibly made to contain the relics of martyrs Gervasius and Protasius under the direction of Ambrose, the bishop of Milan (Watson 1981: 290). Its iconographic programme is similar to Christian funerary art of the same period, suggesting a common meaning.

Around the top of the casket, the apostles are displayed in medallions, with Christ at the centre above the silver lock plate. Below the plate, Christ teaches in the synagogue (Luke 4:16); to the left he heals the woman with the issue of blood (Luke 8:43); and to the right he enters the sheepfold (John 10:1). At the bottom left and centre we see scenes from the story of Susanna (Daniel 13 Vulgate), and on the bottom right Daniel in the lions’ den (Daniel 6). On either side of the lock plate are scenes from the story of Jonah; on the left, Jonah is being tossed overboard into the mouth of the sea monster (Jonah 1:15–17), and on the right, he is being spat back out again (Jonah 2:10). On the back of the casket, in the same position, we find Jonah lying underneath the gourd vine (Jonah 4:6).

The Jonah sequence is frequently found on sarcophagi and in catacomb frescoes, with Jonah appearing more than ten times as often as any other figure, apart from the Good Shepherd (Jensen 2007: 71). The reason for this is that Jonah is intended as a type of Christ. The Sign of Jonah allegory described in the Gospels of Luke and Matthew allowed for the artistic expression of Christ’s salvation in this way, and with it we are given both a portrait of Christ and a theology of salvation.

The three Jonah images are of his death, resurrection, and rest in paradise, and this sequence can be understood to evoke the death, resurrection, and eternal life of Christ.

Like other funerary art, the Brescia Lipsanotheca suggests something profoundly hopeful about the interred bodies of the Christian dead. They are awaiting resurrection. The Jonah sequence can be said to reflect the occupants’ faith in personal salvation from death, and the hope of resurrection and life in paradise.

References

Jensen, Robin. 2000. Understanding Early Christian Art. (New York: Routledge)

______. 2007. ‘Early Christian Images and Exegesis’, in Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art, ed. by Jeffrey Spier (Yale: New Haven)

Watson, Carolyn Joslin. 1981. ‘The Program of the Brescia Casket’, Gesta 20.2: 283–98

El Greco

The Adoration of the Name of Jesus, c.1577–79, Oil on canvas, 140 x 110 cm, Real Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Madrid; Album / Art Resource, NY

The Name of Salvation

Commentary by Lauren Beversluis

Believed to be El Greco’s first commission by the Spanish King Philip II, this painting is considered an allegory of the Holy League of 1571, formed by Spain, Venice, and the papacy against the Ottomans. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, widespread devotion to the Holy Name of Jesus reinforced the League’s mission (Blunt 1939: 58–68).

In the upper register, angels and saints hovering on clouds adore a shining Christogram, ‘IHS’ (from the Greek ΙΗΣΟΥΣ, ‘Jesus’). The left of the lower register exhibits faithful members of the church militant, including portraits of Pope Pius V, King Philip II, and the Doge of Venice, among others. They are kneeling in awe of the sign above, ‘the name that is above every name’ (Philippians 2:9). Juxtaposed at the lower right, the gaping jaws of an enormous sea monster swallow the dead amidst burning flames, and in the background, souls appear under an archway through which they enter purgatory, though some fall into the fiery lake of the beast (Revelation 19:20).

The prominent depiction of death and hell in this painting is graphic and evocative, but the inclusion of the Leviathan is not unprecedented in scenes of the Last Judgement. The sea monster’s long visual history as a symbol of death or hell can be traced all the way back to the earliest Christian iconography, where it appears in connection with Jonah. In El Greco’s painting, a deliverance like Jonah’s is the reward of the faithful and repentant.

In the Gospels, Jesus repudiates those of his generation who are looking for a sign; their faith is much weaker than the Ninevites, who repented at the preaching of Jonah after his deliverance from the sea monster (Jonah 3:5). The importance of a faith which does not rely on visible proof or miraculous signs is reflected in El Greco’s painting, with the adoration of Christ’s name rather than his figure. Jesus refuses to give the people the sign they demand, but instead reveals to them a different kind of sign—a typological one: ‘For just as Jonah was … so will the Son of Man be (Matthew 12:39).

In El Greco’s painting, the risen Word beckons, while a fearsome death in the gaping maw of hell looms threateningly nearby. The prayers of the adoring faithful are thus given a sense of urgency and import, lest we forget the significance of Christ’s salvation.

References

Blunt, Anthony. 1939. ‘El Greco's “Dream of Philip II”: An Allegory of the Holy League’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 3.1/2: 58–69

Simeon Ardjishetsi :

Baptism of Christ, from Gospel by the painter Simeon Ardjishetsi (Simeon of Arces), 1305 , Manuscript illumination

Unknown artist, Italian school :

Reliquary of Brescia (Brescia Casket or Lipsanoteca), front view, 4th century , Ivory casket

El Greco :

The Adoration of the Name of Jesus, c.1577–79 , Oil on canvas

Hope in the Resurrection

Comparative commentary by Lauren Beversluis

If there is one thing that all three of these artworks share, it is the expression of an underlying hope in the resurrection.

This hope for salvation from the power of death is intimately bound up with the person of Jesus Christ. When the scribes and Pharisees ask Jesus for a sign, they may be asking him to show them his true identity. Is he truly the Son of God? What might that mean? A sign may demonstrate his prophetic powers, but Jesus knows that attempting to prove himself through signs will not suffice to convince them who he really is or what his life means for humanity. A mere miracle does not bring about faith in Christ’s salvation. So instead he tells of the Sign of Jonah, which is the sign of his coming death and resurrection. For to know who Christ is, is to know that he is the salvation from the death that he himself undergoes.

The Sign of Jonah, then, becomes a powerful ‘portrait’ of Christ—his person and his work. It is a symbol of his own death and resurrection, but also a representation of the death and resurrection of the faithful he saves.

The symmetrical positioning of the two Jonah scenes that are on the front of the Brescia Lipsanotheca—so as to flank its keyhole—is suggestive. Here the casket, the holding place for the relics of the dead, is opened and closed to receive or release its contents. If Jonah is an allegory for the Christian believer, we can imagine the sea monster in this case as symbolic of the casket, representing not only death and darkness, but a container which holds the body until it is released (or, to push the allegory, regurgitated). The left scene shows the body’s entrance into such death and darkness; the right scene the body’s rescue and resurrection from the tomb. In a funerary context, the meaning is clear: as Jonah was rescued from the great fish and as Christ himself vanquished death and rose again, so too can the faithful look forward to bodily resurrection and eternal life, through Christ’s salvation.

In a similar way to the Jonah sequence, the El Greco painting juxtaposes life and death. But it is much harsher, accusing and commanding the conscience of anyone who looks upon it, testifying to the necessity of a choice between life and death, heaven and hell—and the consequences of that choice. Unlike the monster on the casket, the mouth of this Leviathan represents eternal hell, and not just a temporary sleep anticipating new life on the Last Day. Faithfulness is given heightened importance, as the saved faithful are depicted in disturbingly close proximity to the gruesome alternative end of the faithless. The painting suggests that belief in Christ and being in communion with his Church are urgent requirements for peace in the afterlife. Conspicuously, the faithful adore a floating Christogram, and not a figure of Christ. This suggests that the focus is not so much on the historical person of Jesus, but on the workings of salvation through faith in him, especially faith without visible proof. The Sign of Jonah is all that will be given.

Out of the three works, the manuscript illuminated by Simeon of Arces (or Ardjishetsi) most closely follows the historical biblical narrative in its interpretation of Christ. Rather than a prefiguration or sign of Christ, here he is depicted in the event of his baptism. Still, it conveys much more than that singular event. The inclusion of the vanquished sea monster shows us that this scene has a yet greater significance as an illustration of the power and person of Christ. From above, Christ is blessed by the hand of God and graced with the Holy Spirit in the form of the dove, and he is hailed by a pair of angels. But from below he is threatened by a sinister Leviathan, which is rendered—by the artist, but ultimately by Christ—small and effectively powerless, tied in a knot. It is a cosmic image: Jesus stands between heaven and hell; the divine and beloved Son of God who will conquer death by dying as a man.

In all of these works, the person of Christ is manifested through his salvation from death, both in his own resurrection and in the resurrection of the faithful. The Gospel passages of the Sign of Jonah and these three works are mutually illuminating, together working to reveal the depth of the Christian faith in the risen Christ who saves.

Commentaries by Lauren Beversluis