Matthew 7:13–14, 22–23; Luke 13:22–30

The Narrow Gate

Zara Worth

Think of a door (temptation/redemption), 2022, LED lighting and imitation gold leaf on polythene, Dimensions variable; Image courtesy of the artist.

Moral Uncertainty

Commentary by Zara Worth

In my installation Think of a door (temptation/redemption) forms and motifs borrowed from social media and smartphone designs are tangled up with elements drawn from religious artworks and architecture. The installation comprises two LED sculptures and a large gilded pictorial element.

The pictorial element of the installation is gilded on both sides, each side’s imagery correlating to either the theme of temptation or redemption. For example, the ‘temptation’ side features a reference to Auguste Rodin’s Gates of Hell (modelled 1880–1917, cast 1926–28), while the ‘redemption’ side includes forms borrowed from Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise (1425–52). These artistic precedents are themselves representative of the wide and narrow gates described in the Gospels of Luke and Matthew. However, because the ground of the installation’s pictorial element (on which these forms from Rodin’s and Ghiberti’s artworks are gilded) is clear polythene, the gates of hell and paradise appear knotted together. They are additionally muddled up with numerous references to digital and divine images whose entanglement renders them temporarily morally ambiguous.

The LED sculptures take forms that reference painted frames from religious icons and smartphone bezels and then nest them within one another like matryoshka (Russian dolls). These glowing frames are scaled-up to embody the icon and smartphone’s shared metaphorical status as doorways to immaterial realms. Thanks to the similarity of their shapes, it is impossible without prior knowledge to distinguish which of the coloured frames reference smartphones and which are drawn from religious artworks.

The wide and narrow gates of Luke’s and Matthew’s Gospels, which at face value correlate to predefined ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ ways of living, may not categorize moral decisions as simply as might be assumed. In Luke, we are warned that many, ‘will try to enter and will not be able to’ (13:24), leading to anger and confusion from those denied the entry to the kingdom that they expected. Such uncertainty as to what a threshold might represent is echoed by the composition of Think of a door (temptation/redemption)—speaking to the moral complexity often inherent in decision-making in modern life.

Derek Hirst

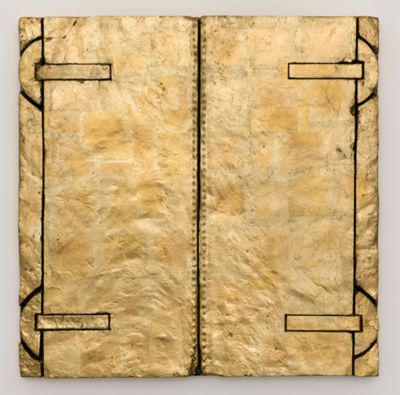

Puerta Grande De Oro, 1998–99, Mixed media on board, 101 x 101 cm; ©️ Derek Hirst Estate, courtesy Flowers Gallery

Push and Pull

Commentary by Zara Worth

The influence of Moorish Andalucía looms large in Derek Hirst’s Puerta Grande De Oro. The artwork’s title discloses both its form and its medium: brightly gilded, the simple composition includes forms that allude to hinges, a frame, and studs running down the centre line where the double doors meet. It is a ‘large golden doorway’.

Notably absent from the construction are any kind of handles or knobs. The inference is that although entry is possible it is not at our discretion, but at the discretion of an unseen other.

Reflecting on his time spent in Andalucía, Hirst mused:

In spite of its many splendid, noisy public ceremonies and rituals, ancient and modern, Andalucía remains to me an enigma—silent and impenetrable, a world of closed doors and shuttered windows which can make one feel desolate from such total exclusion. Yet still as an artist and as a human being, I find it exhilarating and inspirational. (2007: 96)

In Hirst’s work and words, we find a conflicting push and pull between denial of and desire for ingress.

Hirst’s golden door is beguiling and evasive. In Luke’s Gospel Jesus is similarly evasive when asked in the course of his teaching who will gain entry to the kingdom. Joseph Fitzmyer, in his reading of Luke’s Gospel, emphasizes how Jesus avoids giving a definitive answer to this question. As with Hirst’s handle-less golden door, permission to enter is granted from within and is not guaranteed, despite the desires of those seeking admission.

In order to enter the door of the kingdom … one needs more than the superficial acquaintance of a contemporary; one has to reckon with the narrowness of the door and the contest-like struggle (= effort) to get through it. (Fitzmyer 1985: 1023)

Like Hirst in Andalucía, those who are strangers will not necessarily succeed in entering through the narrow door.

If dismayed to learn that few will be granted entry through (or will even succeed in finding) the narrow door that Luke and Matthew describe, we might take encouragement from Hirst’s own resistance to defeat on encountering Andalucía’s closed and impenetrable doors and windows. To Hirst, these closed doors retain a promise sufficiently inspiring to spur on his creativity.

Comparably, the promise of the kingdom that lies beyond the narrow door may energize those who wish to enter through it to strive all the more eagerly to do so.

References

Fitzmyer, Joseph A. 1985. The Gospel According to Luke, 10–24 (London: Yale University Press)

Hélio Oiticica

Penetrável PN1 (installed at Centro de Arte Hélio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro, 2008), 1960, Oil on wood, 203 x 150 x 150 cm, Centro Municipal de Arte Hélio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro; Courtesy Hélio Oiticica Project

Choosing a Way Through

Commentary by Zara Worth

Thresholds are a central image in both Matthew 7:13–14 and Luke 13:22–30. Each Gospel describes a choice between a narrow and a wide gateway. Figuratively, the proposal of a choice between these gateways makes distinct a ‘right’ and a ‘wrong’ spiritual path. In each extract, readers are encouraged to choose the narrow door representing a life following Jesus. By choosing passage through the narrow door, we are promised a righteous life and a place in the kingdom.

The installation PN1 Penetrável (PN1 Penetrable) by Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica is itself composed of narrow doors. PN1 was the first in a series of installations that Oiticica called ‘penetrables’ owing to their construction of spaces that audiences can occupy and reconfigure. PN1 comprises a cabin, painted in bright yellows and oranges, into which a person can enter through sliding panels. Audiences can slide these panels into different positions, determining the configuration of the work for themselves.

The active role played by the audience in the constitution of Oiticica’s work speaks to the significance of choice in Luke and Matthew. As audiences determine the form of PN1, individuals play a role in determining their own narrow and wide gates. Thinking the words of Matthew and Luke through PN1 invites us to think of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ as subject to change rather than as predefined categories, while reminding us of our own responsibility in the determination of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ choices.

Furthermore, as thought through PN1, the metaphoric narrow and wide doors from Luke’s and Matthew’s Gospels may be conceived of as plural rather than singular. The figurative thresholds of the narrow and wide gates might be understood as an infinite number of sliding doors that must be navigated in pursuit of a life well-lived—a life that, like the form of PN1, is not fixed, but in a continual state of becoming.

References

Small, Irene. V. 2016. Hélio Oiticica: Folding the Frame (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

Zara Worth :

Think of a door (temptation/redemption), 2022 , LED lighting and imitation gold leaf on polythene

Derek Hirst :

Puerta Grande De Oro, 1998–99 , Mixed media on board

Hélio Oiticica :

Penetrável PN1 (installed at Centro de Arte Hélio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro, 2008), 1960 , Oil on wood

Thresholds in Determinacy

Comparative commentary by Zara Worth

Reading Matthew’s and Luke’s accounts of the wide and narrow door through artworks by Hélio Oiticica, Derek Hirst, and myself, emphasizes the instability and ethical responsibility at the heart of the determination of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ ways of living.

Oiticica’s work can be thought of as manifesting how the individual is implicated in the drawing of boundaries when we make distinctions between ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ in the world. Hirst’s Puerta Grande De Oro evokes the tension between denial of and desire for passage across boundaries that those seeking ingress do not control. Meanwhile, my own work speaks to the difficulty of knowing for certain what such boundaries might represent morally in an increasingly complex world.

The wide and narrow gates in the Gospels of Luke and Matthew evoke the many kinds of literal and figurative boundary-drawing with which we organise the world and give it meaning.

This process of understanding the world through the determination of material and discursive boundaries is key to feminist theorist and physicist Karen Barad’s theory of agential realism. According to Barad, subjects become knowable through differentiating from within a world that exists in a state of entanglement (Barad 2007). As such, categories of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ can be understood as contingent and iteratively produced.

Barad terms the enactment of such difference ‘agential cuts’ (Barad 2007: 348). Agential cuts are material and/or discursive interventions. They temporarily disrupt entanglement so that difference between subjects can be registered. Such disruptive interventions might be the sliding of panels to determine the new boundaries of a space; the enactment and/or recognition of an exclusion; or stepping across a threshold marking a ‘here’ from a ‘there’. Agential cuts describe the possibility and means by which the world can be re-inscribed or reconfigured.

When we interpret the meaning of the wide and narrow gates in Matthew and Luke’s Gospels, we are discursively enacting agential cuts that distinguish what these figurative thresholds might mean. This distinction may have material consequences in the world—potentially resulting in forms of exclusion and discrimination. It is this capacity of agential cuts to produce, in Barad’s words, ‘marks on bodies’ that reminds us of how high the stakes are when we make such distinctions, and why the questions of accountability and responsibility inherent in the enactment of agential cuts are so urgent (Barad 2003: 817).

At first glance, the wide and narrow doors in Luke and Matthew may appear as neatly predefined ways of organizing the world and ways of living according to rules predefined by God. Certainly, such an interpretation is seductive in its simplicity. However, on closer inspection and read in relation to the artworks of Oiticica, Derek Hirst, and myself, we see them as thresholds that are always in a state of indeterminacy, even for one whose following of Jesus is constant.

The shifting nature of the world’s ordering is underlined at the end of the passage from Luke with the words, ‘Indeed there are those who are last who will be first, and first who will be last’ (13:30). What Luke describes is a vertiginous upending of the social hierarchies with which we are familiar. In this vision of the end of days following God’s judgement, people who have followed a way of life that leads them through the narrow door will find themselves in God’s kingdom, but this is a kingdom which is itself determined by new relations and differences. According to Luke, the social orders that existed on earth will no longer apply and consequently those at the bottom of the social ladder will find themselves at the top in God’s kingdom.

The promise of such radical social reordering provides another reminder that, for the disciple of Jesus, all that matters and has meaning is subject to redefinition

References

Barad, Karen. 2003. ‘Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28.3: 801–31

______. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham: Duke University Press)

______. 2022. ‘Agential Realism—A Relation Ontology Interpretation of Quantum Physics’, in Oxford Handbook of the History of Quantum Interpretations, ed. by Olival Freire et al (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp. 1031–54

Commentaries by Zara Worth