Isaiah 53

Stricken, Smitten, Bruised, and Afflicted

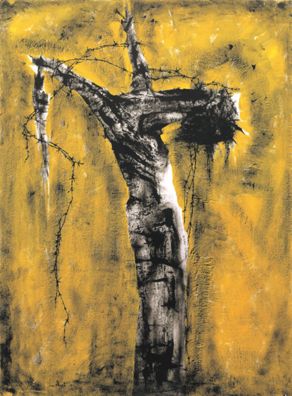

Theyre Lee-Elliott

Crucified Tree Form—The Agony, 1959, Tempera and gouache on paper, 850 x 650 mm, The Methodist Modern Art Collection, London; LEE/1963, © TMCP, used with permission, www.methodist.org.uk/artcollection

The Agony of Sacrifice

Commentary by Jonathan Koestlé-Cate

Crucified Tree Form is one of a series of paintings produced by the artist following a period of grave illness, which had instilled in him a pressing need to paint a crucifixion image (Wollen 2003: 97). In this desolate scene we see body, cross, and tree fused into a 'single, suffering whole' (Ibid, 96–97), in a manner evocatively reflecting the description in Isaiah 53 of the suffering servant, a figure so stricken by afflictions (v.4) that he incites revulsion, scorn, and horror.

The face is blackened and featureless, the arms shattered, the legs a single solid mass embedded in some unspecified, indistinct landscape. The paint is applied in a scumbled, expressionistic manner, and the range of colours is minimal, the lurid yellow background, evoking the putrefaction of death, contrasting starkly with the austere monochrome of the figure. The anachronistic addition of barbed wire deliberately presents the painting in an ambiguous light. One can read it conventionally as a crucifixion: body broken, head bowed, the spikes of the barbed wire resolving into a crown of thorns. Alternatively, it might conjure the ruined landscapes and bomb-blasted trees of the battlefield, or else the mangled corpse of a soldier, entangled in the barbed wire of no-man’s land.

This is not an uncommon analogy to draw: in times of war the crucifixion theme has often become an instrument of social criticism, the religious content perhaps supplanted but perhaps also amplified by the force of the suffering, tortured body immolated on the altar of war. As Isaiah 53 tells us, if the servant suffers and dies—led like a lamb to the slaughter (v.7), cut off from the land of the living (v.8)—he is also exalted. Thus for the modern reader parallels may be drawn with the ennoblement of the fallen soldier in the name of honour, sacrifice, and duty. But so too, as the painting’s subtitle implies, the narrative of the dutiful servant may be open to other, less generous, readings, inevitably souring this particular paean to self-sacrifice.

References

Wollen, R. 2003. Catalogue of the Methodist Church Collection of Modern Christian Art (Oxford: Trustees of the Methodist Collection of Modern Christian Art)

Anish Kapoor

Untitled (The Healing of Saint Thomas), 1996, Cloth; © Anish Kapoor / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London

The Promise of Healing

Commentary by Jonathan Koestlé-Cate

Central to the theme of Isaiah 53 is the expiatory power of the servant’s tribulations. We read, ‘But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that made us whole, and with his stripes we are healed’ (v.5). This verse goes to the heart of Christian interpretations in which the servant is read as Christ. It is given a potent yet simple visual representation, crossing from the Old Testament to the New, in Anish Kapoor’s The Healing of St Thomas.

As part of an installation for the church of Saint Peter, Cologne, Kapoor hung a red cloth, about a square metre and a half in size, beneath the holy water stoup. It had what appeared to be a small diagonal slit, but on closer inspection was in fact a little pouch or pocket that signified a stylized open wound. The hanging cloth had the look of a Mandylion or Veronica—a cloth or veil miraculously imprinted with the image of Christ—but one reduced to the metonym of a single gash, a kind of visual shorthand for the healing power of Christ’s wounds.

In a previous incarnation of this work a slit was made directly into a gallery wall, but for Saint Peter’s Kapoor felt this would imply too literal a response to the building (Kapoor 1997: 39)—figuratively alluding to the church building as the body of Christ—whereas, in Christian dogmatics, the ‘church’ (as body of Christ) is the people. Instead, a red cloth was chosen as the bearer of the wound, becoming a ‘site of spiritual and visual doubt’ (Kapoor 1998: 38). As the lesson of Saint Thomas teaches us, it is by way of doubt that revelation and redemption may be found, just as (with Isaiah 53 in mind) it is via piacular rites—rites of atonement—that healing comes.

References

Kapoor, Anish. 1997. Anish Kapoor (Köln: Kunst-Station Sankt Peter)

———. 1998. Anish Kapoor (London and Berkeley: Hayward Gallery and University of Chicago Press)

Germaine Richier

Christ d'Assy I, 1950, Bronze, 45 cm, Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce, Plâteau d’Assy; © Estate of Germaine Richier; Photo by Hervé Champollion / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Image

A Man of Sorrows

Commentary by Jonathan Koestlé-Cate

In the early 1950s this sculpture for the church of Notre-Dame de Toute Grâce, Assy, was at the centre of a cause célèbre known as ‘la querelle de l’art sacré’, fought over the condemnation of ‘corrupt and errant forms of sacred art’ that had found their way into Catholic churches (Pizzardo 1955: 369). The work was ordered to be removed by the Bishop of Annecy in 1951 and only properly reinstated some twenty years later (Wilson 2006: 66).

It is a cruciform bronze sculpture of a desiccated, lacerated, and near-featureless figure, whose posture incorporates the cross into the figure of Christ, his outstretched arms effectively becoming the horizontal crossbar. Germaine Richier’s uncompromising aesthetic was derided by its critics as a scandalous profanation and sacrilegious deformation of sacred art. Yet to those open to its devotional and liturgical potency, it presented a Christ ‘strong, expressive, powerful, charged with humanity, and palpitating with love’ (Rubin 1961: 51). Indeed, although denounced by the Church as offensive to ‘the faithful’ it was vigorously defended by many parishioners, principally the patients and staff of several nearby sanatoriums, as ‘this man of sorrows, so fraternal to their sufferings’ (Rubin 1961: 52).

Those responsible for its commissioning, including the Dominican priest Fr Couturier, seem perhaps to have anticipated a reactionary backlash, offering a scriptural precedent for the work on a placard accompanying the sculpture, justifying its unconventional form as the embodiment of Isaiah 53:

For he grew up…like a root out of dry ground; he had no form or comeliness that we should look at him, and no beauty that we should desire him. He was despised and rejected by men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief. (vv.2–3)

Writing in defence of the work, Couturier was explicit:

This tortured body, torn to shreds, rough as tree bark, twisted and bent, is the moving vision of Isaiah translated into a cast of bronze.(Couturier 1960, my translation)

References

Couturier, M.-A. 1960. Notre-Dame de Toute Grâce. (Assy: Editions Paroissiales)

Pizzardo, J. C. 1955. ‘Instruction to Ordinaries on Sacred Art’, The Furrow, 6(6): 368–372

Rubin, W.S. 1961. Modern Sacred Art and the Church of Assy (New York: Columbia University Press)

Wilson, S. 2006. ‘Germaine Richier: Disquieting Matriarch’, Sculpture Journal, 14(1): 51–70

Theyre Lee-Elliott :

Crucified Tree Form—The Agony, 1959 , Tempera and gouache on paper

Anish Kapoor :

Untitled (The Healing of Saint Thomas), 1996 , Cloth

Germaine Richier :

Christ d'Assy I, 1950 , Bronze

Song of the Suffering Servant

Comparative commentary by Jonathan Koestlé-Cate

A central motif of Second or Deutero-Isaiah is its concern with ‘the servant of the Lord’. Isaiah 53 (including the final three verses of 52) comprises the last of four so-called Servant Songs written during the period of exile in Babylon (c.540 CE). The identification of this servant remains contentious and the passage as a whole perplexing (Sawyer 2018: 309; Berlin and Brettler 2004: 890–1).

Although unnamed in this song, references to the people of Israel in prior and subsequent passages lend substance to a reading of the servant as a collective figure: Israel, or a faithful portion of Israel (cf. 49:1–6; 54:5–8). But there are also interpretations that set the passage within a Messianic tradition (even though no reference to an individual Messiah can be found anywhere else in Deutero-Isaiah), while others believe it refers to individual figures like Jeremiah or Moses (Baltzer 2001: 392–429), or even the author himself (Orlinsky 1967: 92–3). In sum, what is clear from commentators is that Isaiah 53 not only poses enormous challenges to exegesis, to the extent of being deemed incomprehensible in places, but is also subject to ‘flagrant’ eisegetic distortions (Orlinsky 1967: 70).

For many Christians, of course, the identification of the servant as Christ is unequivocal. The prophetic language of Isaiah 53 appears to express with great clarity and conviction the physical subjection and spiritual apotheosis of Christ in his submission to the will of God (cf. Acts 8:27–35). So strong is this apparent Christological application that this chapter is generally omitted from modern Jewish lectionaries (for a typical example see Berlin and Brettler 2004: 2115–7).

Regardless of the Jewish or Christian, historical or prophetic, individual or corporate identity of the servant, the crux of the passage appears to be its message of vicarious suffering (although this too is vigorously disputed in Orlinsky’s reading as a later Christian gloss on the text). In the Old Testament, suffering is sometimes meted out as a punishment for disobedience (Genesis 3:16–19); sometimes it is more instructive than punitive (Job 23:10); and sometimes it has a larger purpose in God’s plan, whereby suffering, even unto death, is congruent with salvation.

Whether the scandal of the cross is prefigured in Isaiah 53, or read back into it by later Christian hermeneutics, its truly radical message is the transition of an abject and humiliated figure into one exalted by God and, moreover, one whose abasement is inflicted through no fault of his own but in atonement for ‘the transgression of my people’ (v.8). It is ‘a thing without precedent’, says Claus Westermann, ‘epoch-making in its importance’.

That a man who was smitten, who was marred beyond human semblance, and who was despised … should be given such approval and significance, and be thus exalted, is in very truth something new and unheard of, going against tradition and all men’s settled ideas. (Westermann 1969: 259–60)

The passage presents a harrowing picture of the servant’s intercessory role—a role that necessarily goes beyond mere suffering. Indeed, what Isaiah 53 teaches us is that suffering is not intrinsically redemptive. Ultimately, it is the death of the servant, not the magnitude of his suffering, that performs the redeeming work (v.12). Viewed in the light of the Christian message of salvation, there can be no atonement for sin without the death and resurrection of Christ.

Nevertheless, whatever hope of redemption is signified by traditional images of the crucifixion, this hope threatens to be overwhelmed by the harsh brutality of its visual treatment in the hands of Germaine Richier and Theyre Lee-Elliott. The sense of ambiguity reflected in the chapter’s many conflicting interpretations is also evident here. For this reason Richier’s sculpture was subjected to the most vituperative criticism. Yet, as her defenders argued, hers is a transfigured Christ. The terrible suffering and ultimate glorification of Christ is synthesized in its rough and pitted yet gleaming bronze surface. In Lee-Elliott’s rendering of the crucified figure, the servant read as Christ may again be found in this pitiable form, or may allude to other possibilities: whether soldier, saviour, or tree remains uncertain.

Anish Kapoor’s minimal sculptural gesture, meanwhile, draws us back to the opening words of the chapter: ‘Who has believed what we have heard? And to whom has the arm of the Lord been revealed?’ (v.1). As the servant is the manifestation of God’s divine purpose, however imperfectly understood, so The Healing of Saint Thomas reminds us that visual experience and belief are closely interwoven, especially when that visuality employs the very barest, and most allusive, of means.

References

Baltzer, K. 2001. Deutero-Isaiah: A Commentary on Isaiah 40–55 (Minneapolis: Fortress Press)

Berlin, A. and Brettler, M.Z. (eds). 2004. The Jewish Study Bible (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Orlinsky, H.M. 1967. ‘The so-called “Servant of the Lord” and “Suffering Servant” in Second Isaiah’, Studies on the Second Part of the Book of Isaiah (Leiden: E.J. Brill)

Sawyer, J.F.A. 2018. Isaiah Through the Centuries (Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell)

Westermann, C. 1969. Isaiah 40–66: A Commentary (London: SCM Press Ltd.)

Commentaries by Jonathan Koestlé-Cate