John 21:20–25

The Beloved Disciple

James Tissot

Saint Peter and Saint John Run to the Sepulchre, 1886–94, Opaque watercolour over graphite on gray wove paper, 208 x 156 mm, The Brooklyn Museum; Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.332, Bridgeman Images

Apostolic Rivals

Commentary by Ian Boxall

‘Lord, what about this man?’ (John 21:21). Peter’s question hints at a rivalry which has bubbled beneath the surface of the second half of John’s Gospel. Which disciple takes precedence: Peter, or the disciple whom Jesus loved? The latter had reclined in the privileged position of intimacy at the Last Supper, acting as mediator between Peter and Jesus (13:23–25). He had enabled Peter’s access into the high priest’s courtyard (18:15–16) and stayed to witness Jesus’s death after Peter’s denial and flight (19:26–27, 35). On Easter day, the two disciples set off for the tomb together, but the beloved disciple arrived there first (20:4). The rivalry between these two intimates of Jesus continues to the Gospel’s end. ‘Lord, what about this man?’

The French artist James (Jacques) Tissot depicts that tension between Peter and John, albeit here in the earlier scene of their running to Christ’s tomb (20:1–10). One of 365 scenes from the life of Christ, painted following what Tissot called a ‘pilgrimage of exploration’ to the Holy Land, it presents the moment when the beloved disciple reaches the sepulchre.

Following Christian tradition, Tissot’s John is ‘younger and more active than his companion’ (Tissot 1898: 245), well able to outrun Peter. Arriving at the tomb, he is already illuminated by the light emanating from the two angels inside (20:12). Indeed, John himself looks angelic, clothed in dazzling white. Peter, following behind, is still in the shadows, his head turned back towards the city of Jerusalem rather than ahead to resurrection light.

For the community which produced John’s Gospel, Peter may be the shepherd, who confesses his love for Jesus (21:15–19). However, it is the disciple whom Jesus loves who is their direct link to Christ, and who has nurtured them in the faith. His testimony is the testimony they have come to know as true.

References

Tissot, J. James. 1898. The Life of Our Saviour Jesus Christ. Three Hundred and Sixty-Five Compositions from the Four Gospels with Notes and Explanatory Drawings, Volume II (London: Sampson, Low, Marston & Co.)

Plautilla Nelli

The Last Supper, 1560s, Oil on canvas, 7 x 2 m [approx.], Museo di Santa Maria Novella, Florence; Maidun Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

A Supper Remembered

Commentary by Ian Boxall

As the Gospel of John ends, memories come flooding back of that poignant meal in Jerusalem, the night before Jesus suffered. ‘Peter turned and saw following them the disciple whom Jesus loved, who had lain close to his breast at the supper and had said, “Lord, who is it that is going to betray you?”’ (John 21:20). This climactic scene recalls three characters who, in the hours following the Last Supper, would respond in markedly different ways. Peter would deny him; Judas would betray him; the beloved disciple alone would follow Jesus to the cross. Now, post-Resurrection, just two remain: Peter, newly rehabilitated (21:15-19), and the anonymous beloved disciple, whom tradition would identify as John, son of Zebedee.

Those memories shape the central section of Plautilla Nelli’s Last Supper, where all three disciples appear in a single grouping around Christ. Christ tenderly cradles the head of his beloved disciple with his left hand, while offering the morsel to Judas (John 13:26) with his right. The older figure seated to Jesus’s right, bearded and with grey curls, fits conventional depictions of Peter. But it is the intimacy between Jesus and John, the ‘one who is bearing witness’ (21:24), that dominates.

Suor Plautilla Nelli was a sixteenth-century Dominican nun, and prioress of the convent of Santa Caterina di Cafaggio in Florence. According to Giorgio Vasari, her impressive Last Supper was originally displayed in the convent refectory, visible to Plautilla’s religious sisters as they ate together.

Plautilla’s John is conventional: an androgynous figure, the virgin apostle of Christ and type of the contemplative. But this androgyny might have taken on new significance when viewed through the eyes of a female religious, a consecrated virgin ‘Bride of Christ’. For Suor Plautilla and her sisters, this is their story. They recline at Christ’s bosom. And, in their life of contemplation, they bear faithful witness.

References

Falcone, Linda (ed.). 2019. Visible: Plautilla Nelli and her Last Supper Restored (Prato: B’Gruppo Srl)

Nelson, Jonathan K., (ed.). 2008. Plautilla Nelli (1524 – 1588): The Painter-Prioress of Renaissance Florence (Florence: Syracuse University in Florence)

Unknown artist

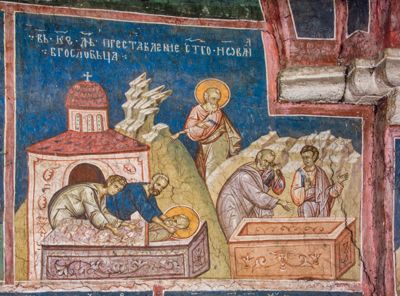

St John the Theologian, the Feast Day of 26 September, The Calendar cycle (or Menologion cycle), 1343–48, Fresco, Narthex of the katholikon of the Dečani Monastery, Kosovo; Courtesy of BLAGO Fund, www.blagofund.org

An Immortal Disciple?

Commentary by Ian Boxall

This final passage of John’s Gospel centres on an ambiguous saying of Jesus, which provoked a rumour. ‘If it is my will that he remain until I come, what is that to you?’ (John 21:22). Did this mean that this disciple would remain alive to witness Christ’s second coming? At least some of the brethren thought so (v.23). Yet the beloved disciple seems to have died by the time this passage was written. Hence the problem, and the need to challenge the rumour.

Yet the rumour was not completely scotched. This saying of Jesus was sufficiently ambiguous to provoke different answers concerning John’s destiny. Augustine knew the story that the earth near John’s tomb in Ephesus continued to move, a sign that John was not dead but sleeping (On the Gospel of John, Tractate 124.2). In one Western tradition, John was destined to wander the earth until the Lord’s return.

Perhaps most widespread in the East is the tradition of John’s metastasis or ‘translation’ (the feast of which is celebrated on 26th September), depicted in this fourteenth-century fresco from Dečani Monastery in Kosovo. The aged John urges his followers to dig a grave for him outside the city of Ephesus. He lies down in the grave, and his disciples return to the city. When they subsequently revisit the burial site, his body is no longer there. One interpretation among Orthodox Christians is that John, like Enoch, Elijah (Genesis 5:24; 2 Kings 2:11–12), and Mary, was translated to heaven.

The Dečani Monastery fresco, like the feast it visualizes, plays on the ambiguity of the dominical saying. On the one hand, John dies in that grave outside Ephesus. On the other, his ‘translation’ means that he is alive in the heavenly realm, where he ‘remains’ until the Lord comes. ‘If it is my will that he remain until I come, what is that to you?’

References

Culpepper, R. Alan. 2000. John, the Son of Zebedee: The Life of a Legend (Minneapolis: Fortress Press)

James Tissot :

Saint Peter and Saint John Run to the Sepulchre, 1886–94 , Opaque watercolour over graphite on gray wove paper

Plautilla Nelli :

The Last Supper, 1560s , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist :

St John the Theologian, the Feast Day of 26 September, The Calendar cycle (or Menologion cycle), 1343–48 , Fresco

Abiding Testimony

Comparative commentary by Ian Boxall

The beloved disciple has bequeathed a powerful legacy to posterity. Of all the books that have or could be written about Jesus (see John 21:25), the Fourth Gospel has been the favourite of many Christians across the centuries. What the second-century theologian Clement of Alexandria called ‘the spiritual Gospel’ or ‘the mystical Gospel’ continues to speak powerfully through its rich symbols, dramatic scenes, and profound dialogues. As the editors of the Gospel’s final version put it, ‘we know that his testimony is true’ (21:24).

But what is the content of that testimony? Plautilla Nelli goes back to that moment of intimacy between Jesus and the disciple he loved, reclining together at the Last Supper. A widespread medieval tradition focussed on this embrace, affirming that the truth about Jesus was revealed to John as he lay on the Lord’s breast and questioned him, and that that insight enabled him to testify to the Word made flesh with his characteristic depth and narrative skill.

The beloved disciple’s testimony would have spoken volumes to Suor Plautilla and her religious sisters, who sought to cultivate the same contemplative intimacy with Christ. The Gospel of John uses a horticultural image to describe that mutual relationship of ‘abiding’: ‘I am the vine, you are the branches. He who abides in me, and I in him, he it is that bears much fruit, for apart from me you can do nothing’ (John 15:5). It may not be coincidental, therefore, that the porcelain on Plautilla’s supper table is decorated with a vine motif (Nelson ed. 2008: 78–79). She and her sisters were striving to abide in Christ, as he abided in them.

James Tissot’s watercolour suggests that the key to this luminous Gospel lies in the revelatory moment at the tomb, where the beloved disciple saw the grave clothes and believed (John 20:8). Tissot depicts John as already illuminated by the divine glory as he approaches the sepulchre (see John 1:1–18). John’s witness—his ability to see beyond the signs of Christ’s life and death to the ‘eternal life’ they convey—has been passed on to subsequent generations in a vivid written narrative. Paradoxically, despite his unexpected death and departure from this world, he ‘remains’ in the Gospel book he has bequeathed to posterity.

For those responsible for the Dečani Monastery frescoes, Jesus’s ambivalence about the beloved disciple’s death is reflected in the image of an aged John, the sole remaining member of the Twelve. Yet John’s story is no solitary narrative. The ending of the Gospel presupposes, not a single Gospel writer, but the witness of a community: ‘we know that his testimony is true’ (21:24b); ‘I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written’ (21:25).

In concrete terms, John’s trustworthy testimony is now bequeathed to his community of disciples. Hence the Byzantine fresco depicts a communal experience. To the left, behind the tomb of John, stands a church, a symbol of the congregation of believers at Ephesus. John is laid in his grave by a pair of Ephesian Christians, the younger of the two probably Prochorus (Acts 6:5), John’s companion and scribe in Byzantine tradition. To the right, Prochorus and an elder discover the tomb empty. In the background, John is visible to the viewer, though not apparently to his first century companions. With his left hand, he gestures us towards the church building. The community, the church, must now take up his mantle as he departs from this world. The testimony that he gave must now be incarnated in concrete human lives.

The testimony of the beloved disciple, then, is multifaceted. For Suor Plautilla Nelli, it springs from an intimate moment at table, when John knew the experience of divine love. Hearing that testimony, others too can know what it means to be disciples whom Jesus loves. James Tissot’s luminous John at the tomb is a reminder that this disciple’s testimony remains for us in written form. John’s Gospel presents a narrative of Christ’s life suffused from beginning to end with resurrection light. In the Dečani Monastery fresco, the testimony is passed on like a baton to those who will follow. That it is particularly lived out in liturgical worship is suggested, not only by the presence of the ecclesiastical building, but by the location of this fresco within the monastic church.

A human life transformed by intimacy with Jesus; a Gospel book; a communal experience. In these ways, and more, the testimony abides until Christ comes.

References

Culpepper, R. Alan. 2000. John the Son of Zebedee, the Life of a Legend (Minneapolis: Fortress)

Dolkart, Judith F., David Morgan, and Amy Sitar, eds. 2009. James Tissot, The Life of Christ: The Complete Set of 350 Watercolors (New York: Merrell Publishers, in association with Brooklyn Museum)

Falcone, Linda, ed. 2019. Visible: Plautilla Nelli and her Last Supper Restored (Prato: B’Gruppo Srl)

Moloney, Francis J. The Gospel of John (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press)

Nelson, Jonathan K., ed. 2008. Plautilla Nelli (1524 – 1588): The Painter-Prioress of Renaissance Florence (Florence: Syracuse University in Florence)

Tissot, J. James. 1898. The Life of Our Saviour Jesus Christ. Three Hundred and Sixty-Five Compositions from the Four Gospels with Notes and Explanatory Drawings, Volume II (London: Sampson, Low, Marston & Co.)

Commentaries by Ian Boxall