Joel 1

Landscapes of Devastation

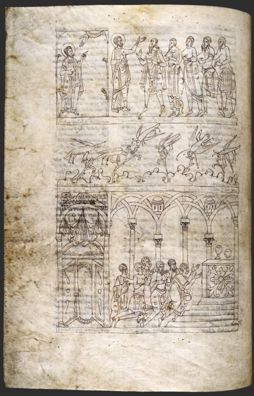

Unknown Catalan artist

Joel, from Biblia Sancti Petri Rodensis (The Roda Bible), 901–1100, Illuminated manuscript, tempera on parchment, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Manuscrits, Paris; Latin 6 (3), fol. 77v, ark: / 12148 / btv1b85388130

Illuminating the Salient

Commentary by Jennifer Sliwka

This illumination is from one of the finest extant eleventh-century Catalan manuscripts: a Bible made for the monastery library at Sant Pere de Rodes (known as the Roda Bible). Including extensive Old Testament pictorial cycles, it is especially rare because of the rich illustrations of the Prophets.

In this example, salient events from Joel 1 have been represented as a series of literal events: his reception of the word (v.1) and preaching (vv.2–3) in the top register; the plague of locusts (v.4) at the centre; and the priests kneeling before the altar in the temple (vv.9, 13) in the lowest register. At the upper left, Joel stands within a delicate architectural framework, receiving the word of the Lord through divine means (represented by a disembodied hand, a motif often used by artists to represent Moses’s reception of the Law). Joel reappears in the scene at the right, his raised left hand and open palm indicate that he is preaching to the group of men, young and old, before him. Raised and seemingly floating above the ground, Joel is given special prominence over his attentive audience. The Prophet is also distinguished by his halo and bare feet, the latter calling to mind Moses’s humble removal of his sandals before the burning bush (Exodus 3:5). The assembled group must represent the elders and their children to whom Joel preached about the locust plagues, the large winged insects occupying the centre of the page. The locusts devour the remaining vegetation in an otherwise barren landscape, suggested by the curious undulating surface represented beneath them.

The lowermost scene likely represents the priests ministering before the altar during this plague, but neither their expressions nor their dress particularly suggest the state of mourning Joel describes. Further, while their toga-like robes imply an event in the distant past, the design of the temple recalls Catalan Romanesque architecture. These details give the events described in Joel a contemporary resonance, suggesting that the priests and monks of Sant Pere de Rodes were meant to recognise themselves in these biblical figures.

Piero di Cosimo

The Forest Fire, c.1505, Oil on panel, 71.2 x 202 cm, Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford; Presented by the Art Fund, 1933, WA1933.2, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, UK / Bridgeman Images

Devouring Flames

Commentary by Jennifer Sliwka

Piero di Cosimo’s masterful rendering of the frightened, charging animals attempting to escape a forest fire, the intense sparking blaze visible in the middle distance of this landscape, recall Joel’s description of the fire that devoured the wilderness and deprived the beasts of home and sustenance.

Piero probably painted this panel, however, as part of a series inspired by passages from Book 5 of De Rerum Natura (‘On the Nature of Things’) by Lucretius (98–c.55 BCE), who traces the origins of life on earth and the birth of community life, emphasising the role of fire as a catalyst for change. Although the artist was interpreting a classical source, when considered in light of Joel 1:18–20, the painting may also be read as an example of the devastation that precedes the deliverance of Israel as described in Joel 3:16–21. The open, gasping mouths of the animals in the foreground of Piero’s panel, especially the bull who extends his long pink tongue, suggests their panting and thirst after fleeing the fire, but also calls to mind Psalm 42:1: ‘As the deer pants for streams of water, so my soul pants for you, my God’. Read in this light, the flames and the thirst of the beasts so vividly rendered by Piero might also stand for the ardent desire to know or be close to God.

Piero’s painting also suggests a particular affinity between animals and humans, as some of his beasts possess human faces. This extraordinary depiction suggests a world in which the divisions between animals and humans are not distinct and which speaks to both the shared desires and sufferings of all living beings as described in Joel.

References

Geronimus, Dennis. 2006. Piero Di Cosimo: Visions Beautiful and Strange (New Haven: Yale University Press), pp. 134–36

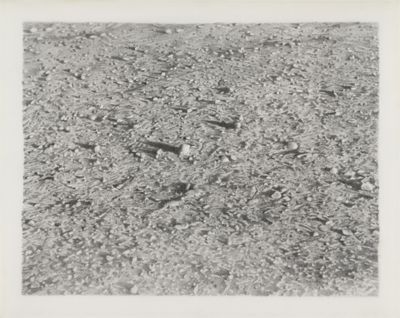

Vija Celmins

Untitled (Irregular Desert), 1973, Graphite on synthetic polymer ground on paper, 30.5 x 38.1 cm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Gift of Edward R. Broida, 678.2005, © Vija Celmins / Matthew Marks Gallery; Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

A Landscape of Desolation

Commentary by Jennifer Sliwka

Joel describes the drought, the withering of the crops and trees, and the subsequent famine at length in an effort to mobilise the indifferent to repentance.

In his commentary on this passage, the fifth-century theologian Theodoret of Cyrus attributed the cause of the land’s infertility to the lawlessness of the people who ‘confounded joy’ and whose happiness, therefore, withered like the dried crops. Accordingly, the barren landscape described in Joel might equally be associated with a psychological or spiritual desolation.

This photo-realistic drawing of a rocky desert by Vija Celmins, a Latvian-American artist known for her paintings and drawings of natural environments, helps us imagine the state of the earth following the drought and withering of crops described by Joel. Using one of her own photographs of the Mojave Desert, northeast of Los Angeles, Celmins executed this fine drawing in a meticulous and time-consuming technique using graphite pencil on paper prepared with synthetic polymer ground. The surface texture of the dry earth is rendered so that it completely fills the picture plane, unbroken by the horizon, a building, or any form of life.

Celmins has described her painstaking drawing process as ‘thinking’, and as a means of ‘moving from one place to another’; therefore, the creation of this work might also be understood as a record of a kind of psychological movement. Untitled (Irregular Desert) conveys a sense of emptiness and loneliness: a vastness that simultaneously suggests an engulfing or an oppressive barren landscape—a sense that is compounded by the absence of colour. Indeed, Celmins’s use of grey, a colour long associated with mourning, in this work makes it an especially powerful evocation of the ‘mourning’ ground described in Joel (v.10).

References

Ferreiro, Alberto (ed.). 2003. The Twelve Prophets, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, Old Testament, 14 (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press)

Theodoret of Cyrus. 2006. Commentary on the Twelve Prophets, Commentaries on the Prophets, 3, trans. by Robert C. Hill (Brookline, Mass: Holy Cross Orthodox Press)

Unknown Catalan artist :

Joel, from Biblia Sancti Petri Rodensis (The Roda Bible), 901–1100 , Illuminated manuscript, tempera on parchment

Piero di Cosimo :

The Forest Fire, c.1505 , Oil on panel

Vija Celmins :

Untitled (Irregular Desert), 1973 , Graphite on synthetic polymer ground on paper

A Landscape Consumed

Comparative commentary by Jennifer Sliwka

The overall tenor of Joel 1:1–20 is one of devastation. The desolate language such as ‘laid waste’, ‘stripped off’, ‘ruined’, ‘dried up’, ‘withered’, ‘cut off’, ‘shrivelled’, and ‘devoured’ creates a bleak vision of both the earth and humanity. These words are associated with death and mourning, and while such terms describe a dramatic ‘stripping back’ or ‘pruning’ of the landscape, they also imply a return to an earlier, less fraught, or more pristine state: ‘[the army of locusts] has stripped off their bark…leaving their branches white’ (v.7). Indeed, while the plague of locusts and the subsequent drought and famine described in Joel brings devastation and suffering, it also offers a new beginning (anticipating the deliverance of Israel in Joel 3). Similarly, the call for fasting and prayer in this passage (vv.14, 19) indicates the hope for redemption, suggesting that the devastation which has laid them bare has also made way for a kind of renewal or rebirth.

The Catalan manuscript illumination and its tripartite structure provides a quite literal and direct representation of the salient events in Joel 1, while the underlying spiritual themes and meanings are perhaps better explored through the indirectly related works by Vija Celmins and Piero di Cosimo. For example, we may imagine that the locusts devouring plants at the centre of the Catalan manuscript will soon render the landscape much like the barren ground in Celmins’s photo-realistic drawing. In Celmins’s work, the cracked earth and dusty rocks fill the entire picture plane, conjuring up the choking heat and relentless dry terrain we associate with deserts, and providing little sense of life. However, Celmins’s attentive artistic process—which she describes as a kind of psychological movement from one state to another—suggests the possibility of change. This aspect of Celmins’s meditative artistic practice may be likened to the ‘ministering of the priests before the altar’ (v.13) whose lamentation, repentance, and prayer (as seen at the bottom of the manuscript) will ultimately bring deliverance. Similarly, we may interpret the inclusion of a eucharistic chalice and paten on the altar of the temple represented in the manuscript as a typological prefiguration of another kind of sacrifice that will bring human salvation.

The notion of ‘stripping back’ reiterated in the text of Joel and suggested by the absence of everything but the dry earth in Vija Celmins’s desert landscape is also suggested by the engulfing flames of Piero’s Forest Fire. Indeed, the long-standing association between fire and purification can be traced back to antiquity and is found in numerous biblical passages such as those referring to the refiner’s fire (Zechariah 13:9; Isaiah 48:10) which was used to bring precious metals to their finest or purest state. Here, the devouring action of the flames can be likened to that of the locusts, and both may be associated with the final judgement on the ‘day of the Lord’ described in Joel (v.15). Reducing the landscape once again to bare earth, the locusts and the flames perform a kind of ‘re-pristination’ of the land, rendering it fit for a new age.

Commentaries by Jennifer Sliwka