Psalm 39

Let Me Know Mine End

Works of art by Unknown artist, Reims/Hautvillers, Unknown English artist and Unknown French artist

Unknown artist, Reims/Hautvillers

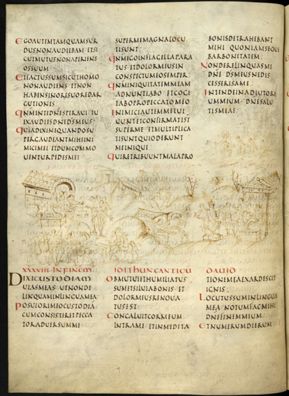

Psalm 38, from the Utrecht Psalter, c.830, Illuminated manuscript, 330 x 255 mm, Utrecht University Library; MS Bibl. Rhenotraiectinae I Nr 32, fol. 22v, Courtesy Utrecht University Library

Hanging by a Thread

Commentary by Frederica Law Turner

The Utrecht Psalter is one of the greatest manuscripts of the Carolingian renaissance. Produced probably at Hautvilliers, the Latin text was written almost entirely by one scribe and illustrated by a number of artists following a single design. Each psalm is introduced by a vibrant drawing, done in pen and wash, spread across the whole of the page. Set in a mountainous landscape teeming with men and animals, angels and demons, these illustrate specific phrases of the psalm text in quite literal ways.

At Psalm 38—Psalm 39 in most modern versions of the Bible—the psalmist stands at top centre, his hands covering his mouth (‘I will take heed to my ways: that I sin not with my tongue’; v.1 Douay-Rheims). Before him are an open coffin and three demons: one with a trident, one with a tape measure, and a third counting on his fingers (‘O Lord, make me know my end. And what is the number of my days…Behold thou hast made my days measurable’; vv.4–5). All gaze up at Christ and three angels hover in the sky at the top right. Below, a spider’s web hangs between two plants (‘thou hast made his soul to waste away like a spider’; v.12).

We do not know for whom the Psalter was made, but it was not meant for use in the liturgy. It may have been made for a court official, perhaps even Louis the Pious himself (814–40). The colourful archbishop Ebbo (d.851), the childhood companion and later the librarian of Louis, seems to have been responsible for the extraordinary artistic flowering which made Rheims the centre of Carolingian painting in the second decade of the ninth century.

The whole of the lower part of the illustration for this psalm is devoted to illustrating the vanities of the world, alluded to in verses 6 and 7 (‘And indeed all things are vanity, every man living…he storeth up, and he knoweth not for whom he shall gather these things’). To the right, a king seated on a throne supervises the gathering of his riches which, brought on the backs of camels and horses, are weighed and counted and put away in chests. The Psalter’s extensive depiction of worldly riches, while commenting on their ephemerality, perhaps had a particular resonance for the original owner of the manuscript.

References

Van der Horst, Koert, et al (eds). 1996. The Utrecht Psalter in Medieval Art: Picturing the Psalms of David (MS't Goy: HES Publishers)

Unknown French artist

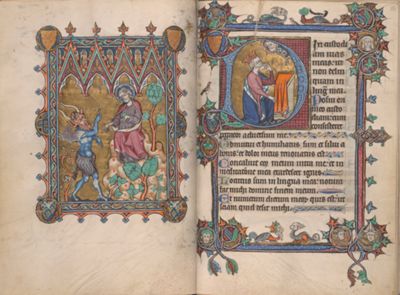

Psalm 39 (38 Vulgate) and the Second Temptation of Christ, from the Psalter–Hours of Yolande of Soissons, c.1280–90, Illuminated manuscript, 182 x 134 mm (closed), The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; MS M.729, fols 55v & 56r

Psalmed Combat

Commentary by Frederica Law Turner

This small but deluxe Psalter–Hours, now in the Morgan Library in New York, was made in the late thirteenth century for Comtesse de la Table, Dame de Coeuvres, and was adapted by her step-daughter, Yolande de Soissons, by whose name it is usually known.

The manuscript is a kind of private devotional compendium, incorporating the Psalms and canticles, and a variety of other texts, including the Hours of the Virgin, of the Cross, and of the Holy Ghost, and the Office of the Dead. It also boasts thirty-nine full-page miniatures, survivals of an originally larger set, as well as sixty-six historiated initials and calendar illustrations, making it one of the most extensively illustrated books of the period.

The layout is unusual, with miniatures distributed through the text rather than grouped together at the beginning. In the Psalter, large, illuminated initials mark the eight-fold division of the Psalms. At Psalm 38 (Psalm 39 in most modern versions of the Bible), King David kneels in repentance before God and points to his mouth. This is a conventional scene for this psalm, reflecting the opening words of the text: ‘I said: I will take heed to my ways that I sin not with my tongue’ (v.1 Douay-Rheims).

Facing this is a full-page miniature of the second temptation of Christ, as told by Luke (4:5–8). Christ, seated on a rocky hillock—the high mountain of Luke’s text—is in conversation with a blue, hairy devil. The devil points both up and down, inviting Christ to bow down and adore him. Christ however firmly displays a book—the book of Deuteronomy—from which he quotes, ‘Thou shalt adore the Lord thy God, and only him shalt thou serve’ (cf. Deuteronomy 6:13).

This is one of six miniatures of the Ministry of Christ which originally marked the divisions of the Psalms into groups for recitation as part of the Divine Office. We start with the First Temptation (now lost) at Psalm 1, then the Second Temptation at Psalm 26, and the third at Psalm 38. The choice of these subjects reflected the medieval concept that the recitation of the Psalms was a crucial part of the battle against temptation for clerical and lay viewers.

Unknown English artist

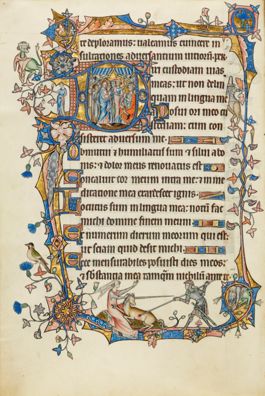

Psalm 38, from the Ormesby Psalter, 1250–1330, Illuminated manuscript, 377 x 250 mm, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford; MS Douce 366, fol. 55v., Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

The Spiritual Unicorn

Commentary by Frederica Law Turner

The majestic Ormesby Psalter is one of the most important of a group of deluxe manuscripts made for East Anglian patrons in the first half of the fourteenth century. Named after Robert of Ormesby, monk and probably subprior of Norwich in the 1330s, the manuscript was decorated in a series of campaigns (or phases of work) for successive patrons from the late thirteenth century.

Richly decorated in burnished gold and glowing colours, the Psalter boasts an astonishing wealth of illumination, with large historiated initials and full borders marking the ten-fold division of the Psalms. At Psalm 38 (Psalm 39 in modern versions of the Bible), we see the trial of Christ as described by John (18:28–40), an unusual but appropriate subject for a psalm whose theme is the patience of the just man in the face of accusation. Pilate and Christ are surrounded by a motley crew of accusers, some caricatured to emphasize their difference from the Psalter’s aristocratic patrons (and to express the widespread anti-Jewish prejudices of the period).

The images in the borders also comment on the text, or on the initial scene. Here, next to the initial, a dog-headed grotesque in a women’s dress looks across at her male counterpart in the opposite border. Christ was described by medieval exegetes as being led to his trial by dogs, and the raised hand on the end of the female’s tail parodies the gesture of the lead accuser in the initial.

In the lower border we see the Hunt of the Unicorn. According to the bestiary, the unicorn is so fierce that it can only be captured by a trick. A virgin is left alone in the forest and as soon as the unicorn sees her it springs into her lap, and allows itself to be killed by the hunter. This story was generally interpreted as an allegory of the Incarnation, but here it seems to relate to the Trial of Christ in the initial. According to the thirteenth-century Bestiary of Guillaume le Clerc, Jesus Christ, ‘the spiritual unicorn’, was not recognized by the Jewish people, who:

believed him not, but spied on him

And then took him and bound him.

Before Pilate they led him

And there condemned him to death. (BNF fr. 14969)

The metaphorical link between the unicorn and the Christ is emphasized by the prominent wound in the unicorn’s side, which reminds the viewer of Christ’s wounding at his Crucifixion.

References

Law Turner, Frederica C. E. 2017. The Ormesby Psalter: Patrons and Artists in Medieval East Anglia (Oxford: Bodleian Library Publishing)

Unknown artist, Reims/Hautvillers :

Psalm 38, from the Utrecht Psalter, c.830 , Illuminated manuscript

Unknown French artist :

Psalm 39 (38 Vulgate) and the Second Temptation of Christ, from the Psalter–Hours of Yolande of Soissons, c.1280–90 , Illuminated manuscript

Unknown English artist :

Psalm 38, from the Ormesby Psalter, 1250–1330 , Illuminated manuscript

Evidence of Endurance

Comparative commentary by Frederica Law Turner

More illuminated Psalters have come down to us from the Middle Ages than any other book of the Bible. The Psalms stood at the heart of the Christian liturgy, making up the core of the Mass and the Divine Office, and were the major component of private prayer, both for clergy and the laity. All 150 Psalms were recited every week by monks through the eight daily hours, and this emphasis spread to laity, who imitated public forms of liturgy in private devotional exercises.

In the ninth century, Alcuin of York (c.735–804) wrote a programme of devotion for the Emperor Charlemagne which included much material from the Psalms, and from the twelfth-century richly decorated Psalters were used by the wealthy laity as a form of personal prayerbook, only supplanted by the Book of Hours in the fourteenth century.

Psalters, however, presented a problem for the medieval artist. The Psalms, written originally in Hebrew and attributed in the Middle Ages to the authorship of King David, are songs of despair, hope, faith, protest, lamentation, and supplication. What they are not, unlike many other books of the Bible, is narrative and this makes them challenging to illustrate.

Artists evolved various strategies for coping with this problem. By the thirteenth century, a fairly standard set of artistic subjects marked the division of the Psalms into groups for recitation as part of the Divine Office, starting with Psalm 1 at Matins on Sunday. These either depicted David—the supposed author of the Psalms—or Christ—their supposed referent. David is usually shown either in a scene from his life or more literally acting out the opening words of the psalm, as at Psalm 38 (Psalm 39 in modern versions of the Bible) in the Psalter of Yolande of Soissons.

Alternatively, scenes from the life of Christ reflected the traditional interpretation of the Psalms as typological, so as prefiguring events in Christ’s life. So, in the Ormesby Psalter, the Trial of Christ is illustrated at Psalm 38: a relatively unusual subject found occasionally in late thirteenth-century French Psalters.

The third method of psalm illustration appears in the earliest manuscript in this exhibition: the literal depiction of words and phrases from the text. This concept seems to have had its roots in late classical and early Christian book art: similarities between literal illustrations in ninth-century Byzantine Psalters, in the Carolingian Stuttgart Psalter, and the Utrecht Psalter suggest that all were drawing on a common tradition. No other manuscript, however, attempted the Utrecht Psalter’s extraordinary feat of using the words of the text as a kind of jumping off point for extensive compositions combining multiple elements into a visualization of the whole psalm.

This tradition was introduced into England when the Utrecht Psalter made its way to Canterbury, where it was copied three times between c.1000 and c.1200. Its literal way of thinking about the Psalms—using individual words or phrases of the text as an immediate inspiration—percolated widely through English manuscript illustration. Many of the puzzling marginal images which so characterize English illumination can be understood as responses to words in the text, as visual jokes or puns on words. The dog-headed beast biting an acorn in the margin of Psalm 38 in the Ormesby Psalter was perhaps inspired by the many references to tongues and mouths in the text next to him.

There is indeed much to chew on in this psalm, of which one early commentator remarked: ‘[It] is instructive beyond any other, capable of giving more than adequate instruction in how to give evidence of endurance in the midst of hardships’. (Theodore of Mopsuestia, Commentary on Psalms 39.1)

References

Stones, Alison. 2004. ‘The Full-Page Miniatures of the Psalter-Hours New York, PML, ms M.729: Programme and Patron, With a Table for the Distribution of Full-Page Miniatures within Text in some Thirteenth-Century Psalters’, in The Illuminated Psalter: Studies in the Content, Purpose and Placement of Its Images, ed. by F.O. Büttner (Brepols: Turnhout), pp. 281–307

Commentaries by Frederica Law Turner