Matthew 6:9–15; Luke 11:1–4

The Lord’s Prayer

Works of art by Rembrandt van Rijn, Unknown Byzantine artist and Unknown Netherlandish artist

Rembrandt van Rijn

The Return of the Prodigal Son , 1636, Etching, 156 x 138 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Bequest of Harry G. Friedman, 1965, 66.521.49, www.metmuseum.org

The Father Forgives as We Forgive

Commentary by Jane Heath

Rembrandt van Rijn’s etching of the return of the prodigal son alludes to a Lukan parable (Luke 15:11–32) and highlights a moment in it that resonates with the petition for forgiveness at the heart of the Lord’s Prayer: ‘Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us’. The humdrum earthiness of Rembrandt’s vignette underscores that human forgiveness is an integral part of how we receive and recognize divine mercy. By contrast with the two servants in the doorway who recoil in disgust and the third who gawps insolently from the window, the father opens himself unreservedly to the son’s embrace, bending forward, bowing down, touching him, and welcoming his touch.

There is a sharp contrast between the father and his son: he is clothed and shod, his son is half-naked and barefoot; he is coming down from a higher place, the son kneels after climbing from a lower place; he is old, his son is young; his face is clean and comely, his son’s is soiled and disfigured.

But those differences are overcome in the embrace. Their sealed lips, downturned eyes, and bowed heads communicate not only their receptivity toward each other, but also their posture of prayer in silent thanksgiving to their Heavenly Father. Here forgiveness is complete, and the deformed visage of the half-starved youth is caught up into a humanizing bond of love and mercy. He had come home because he was hungry and so ‘came to himself’ and realised that he had sinned before heaven and before his earthly father (Luke 15:17–18).

So too in the Lord’s Prayer Jesus brings people back to the proper I-Thou relationship to the Father, to relearn the humility to hallow His name and seek His will, and the self-awareness to plead for bread and for mercy. Rembrandt makes vivid the personal relationship of love and forgiveness in which this transformation is possible.

References

Durham, John I. 2004. The Biblical Rembrandt: Human Painter in a Landscape of Faith (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press)

White, Christopher. 1999. Rembrandt as an Etcher, 2nd edn. (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Unknown Byzantine artist

The Annunciation, c.1151, Mosaic, La Martorana, Palermo; © Vanni Archive/ Art Resource, NY

The Virgin Prays ‘Thy Will Be Done’

Commentary by Jane Heath

When Gabriel came to Mary with the promise that she would conceive and bear a son who would sit on David’s throne and rule forever, Mary gave her whole self in assent: ‘Behold the servant of the Lord; be it unto me according to Thy Word’ (Luke 1:38).

The bema mosaics in this Byzantine church from Norman Sicily depict the moment when the Holy Spirit entered the Virgin, sent by the hand of God from the heavenly hemisphere. The gesture of the divine hand signifies speech, as God’s Word is made flesh (John 1:14).

In this ecclesial setting, the scene is positioned over the entrance to the sanctuary, so that it frames the liturgical mystery of Transubstantiation in light of the historical mystery of the Incarnation. The motif of Mary spinning the scarlet threads of the Temple veil (Prot. Jac. 11) hints at the Passion, for at Jesus’s death the veil of the sanctuary was torn in two (Mark 15:38); it was by the veil of his flesh that he opened a ‘new and living path’ to God (Hebrews 10:20).

This scene can be contemplated as a commentary on the Lord’s Prayer, since the Annunciation reflects its petitions. This is how the Son of God came into the world, that ordinary people could discover a relationship to God as ‘Our Father’. The angel’s promise of a royal Son is how God’s ‘kingdom comes’; Mary’s response echoes ‘Thy will be done’. By yielding her body for the Word to be enfleshed, she allows God’s will to be done ‘on earth as in heaven’.

The location of the scene over the sanctuary recalls that God nourishes his people with the ‘daily bread’ of the Eucharist, while the motifs that allude to the passion underscore both the personal costliness of Mary’s fiat, and the grounds for believers’ confidence that the Father through the Son could indeed ‘forgive us our trespasses’ and ‘deliver us from the Evil One’.

References

Kitzinger, Ernst. 1990. The Mosaics of St. Mary’s of the Admiral in Palermo, with a Chapter on the Architecture of the Church by Slobodan Ćurčić (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oakes)

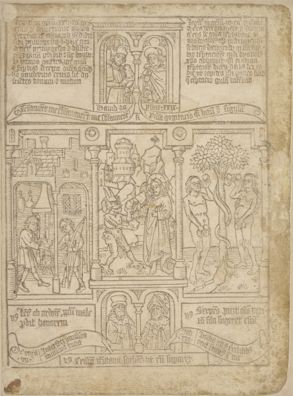

Unknown Netherlandish artist

Temptation in the wilderness, flanked by the Esau selling his birthright, and the fall, from Biblia Pauperum, c.1465, Woodcut, 262 x 192 mm, The British Museum, London; 18,450,809.11, © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Tempted by Satan and Delivered through Christ

Commentary by Jane Heath

Between the thirteenth and the fifteenth centuries, block book Bible commentaries—printed using woodcuts—were widely distributed. Today they are known as Biblia Pauperum, although they were not typically made for the very poor and could be quite costly. They contextualize Christian tradition in relation to Old Testament narratives and prophecies.

We see a page of one here. Its Latin titulus can be translated, ‘Satan tempted Christ in order that he might overcome him’, and the central section portrays Christ’s temptation in the wilderness, where he fasted for forty days (Matthew 4:1–11; Luke 4:1–13; cf. Mark 1:12–13). In the background, the city and the precipitous mountain recall how Satan tempted Jesus to accept earthly dominion in return for homage, and to prove God’s merciful protection by flinging himself from a high rock.

Most prominent, however, is the encounter in the foreground where Satan tempts him to turn stones into bread to satisfy his hunger. In the adjacent sections, interpreted through textual glosses above and below, Esau (at left) prioritizes a tasty meal over his father’s blessing and honour, and (at right) Satan tricks Adam and Eve to expect godlike knowledge from eating. By contrast, Jesus, at centre, lifts his hand to touch, but not to taste, the stone.

The prophets, portrayed two-by-two above and below the central scenes, hold inscribed banderoles, through which God chastises his wayward people and declares his victory over the enemy (above: Psalm 34:16; Isaiah 29:16; below: 2 Kings 7:9; Job 16:10). The composition as a whole argues that God gained victory over Satan by Christ’s obedience, thereby fulfilling what the prophets had called for but humanity had neglected from the first.

As a devotional aid to meditation on temptation, this page captures the tension between human frailty and hope in God that is expressed in the closing petition of the Lord’s Prayer, ‘Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil’. By focusing attention on how Christ defeated Satan where all humanity had failed, the Biblia Pauperum strengthens confidence in God’s sovereignty to defeat evil, including even the evil that works insidiously through carnal appetites and self-directed desires.

References

Henry, Avril. 1981. ‘The Forty-Page Blockbook “Biblia Pauperum”: Schreiber Editions I and VIII Reconsidered’, Oud Holland 95.3: 127–50

Labriola, Albert C., and John W. Smeltz (trans.). 1990. The Bible of the Poor (Biblia Pauperum): A Facsimile and Edition of the British Library Blockbook C.9 d.2 (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press)

Rasmussen, Tarald. 2008. ‘Bridging the Middle Ages and the Renaissance: “Biblia Pauperum”, their genre and their hermeneutical significance’, in Hebrew Bible/Old Testament: The History of its Interpretation, vol. 2, ed. by Magne Saebø (Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht), pp. 76–93

Rembrandt van Rijn :

The Return of the Prodigal Son , 1636 , Etching

Unknown Byzantine artist :

The Annunciation, c.1151 , Mosaic

Unknown Netherlandish artist :

Temptation in the wilderness, flanked by the Esau selling his birthright, and the fall, from Biblia Pauperum, c.1465 , Woodcut

The Lord’s Prayer and Christian Art

Comparative commentary by Jane Heath

The three objects in this exhibition are drawn from different periods, different artistic media, and different theological and ecclesial traditions. None of them sets out to portray the Lord’s Prayer directly. In fact, their subject matter derives from three distinct genres of scriptural writing and reception: realistic narrative, parabolic speech, and typological reflection. Despite the diversity, there is an artistic thread that holds them together through a logic that is scriptural and theological. By viewing them in relation to the Lord’s Prayer, we discover how art and Scripture work together in Christian devotion.

We begin with some differences. The mosaics from the Church of St Mary the Admiral in Palermo were commissioned by George of Antioch, an Orthodox Greek who was prominent in the court of the first Norman king of Sicily, Roger II. The Norman rulers had already begun a programme of building and adorning Sicilian churches in Byzantine style, and the Annunciation at St Mary’s recalls the same scene in the royal Palatine chapel nearby. The idea that God’s kingdom should come was, in the sight of the Norman rulers, closely bound up with their own status as anointed kings.

Rembrandt van Rijn, by contrast, inhabited the world of the Dutch Reformation, where art was banned from churches, but the biblical text was one of his primary sources and inspirations. This version of the Return of the Prodigal draws attention to his sympathy with outcasts. He frequently portrayed beggars and peasants, and the prodigal son is one of them, thin, scruffy, and disfigured. His strong personal identification with the prodigal emerges in another painting from this period, known as The Prodigal Son in the Tavern (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden), where Rembrandt figured himself as the wayward son, squandering his money on drink in the alluring company of women.

The Biblia Pauperum is different again. A late medieval creation for wide distribution in its printed forms, it was probably intended for private devotion among educated lay readers. The design of the page demanded literacy, scriptural knowledge, and time to pause and contemplate the relationship between the many different parts, both images and texts. The individual artist of the page recedes, and in his place emerges a whole tradition of typological thinking about the relation between the Old Testament and Christianity.

Despite the diverse contexts and characteristics of these three artworks, and despite the fact that none of them has the Lord’s Prayer as its subject matter, each has deep points of connection with that prayer of prayers.

Firstly, all three artistic compositions focus attention on gospel stories. This is important to how and why it is fruitful to read them in relation to the Lord’s Prayer. To live out a life that is shaped by that prayer would necessarily take narrative form, since earthly life happens across time. Where better to discover narrative paradigms for such a life than in the gospel stories about Jesus, who taught the prayer to his disciples? These are the stories that his disciples put together of things that he said and did. Their purpose, like that of the Lord’s Prayer, was to form people in relation to God through Christ. Therefore there is a devotional logic embedded in the Christian tradition that encourages us to contemplate gospel stories in light of the Lord’s Prayer, and vice versa.

Second, all three artworks implicitly or explicitly present human experiences of embodied life in relation to the God who calls humanity into ordered and loving relationships through Christ. The artistic media give embodied form to this relationship and locate it in space: the moment of Incarnation is over the sanctuary; the prodigal is portrayed as he returns home; the block book facilitates practices of meditation in a domestic setting. Through these uses of material form to represent and locate embodied devotion, the artistic media help to realise the interplay of heaven and earth, sin and forgiveness, temptation and deliverance, which strikes to the core of the human experience that the Lord’s Prayer seeks to refocus and to transform.

References

Borsook, Eva. 1990. Messages in Mosaic: The Royal Programmes of Norman Sicily 1130–1187 (Rochester, NY: Boydell Press)

Held, Julius S. 1984. ‘A Rembrandt “Theme”’, Artibus et Historiae 5.10: 21–34

Kitzinger, Ernst. 1990. The Mosaics of St. Mary’s of the Admiral in Palermo, with a Chapter on the Architecture of the Church by Slobodan Ćurčić (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oakes)

Rasmussen, Tarald. 2008. ‘Bridging the Middle Ages and the Renaissance: “Biblia Pauperum”, their genre and their hermeneutical significance’, in Hebrew Bible/Old Testament: The History of its Interpretation, vol. 2, ed. by Magne Saebø (Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht), pp. 76–93

White, Christopher. 1999. Rembrandt as an Etcher, 2nd edn. (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Commentaries by Jane Heath