Mark 16:1–8

In My End Is My Beginning

Clyfford Still

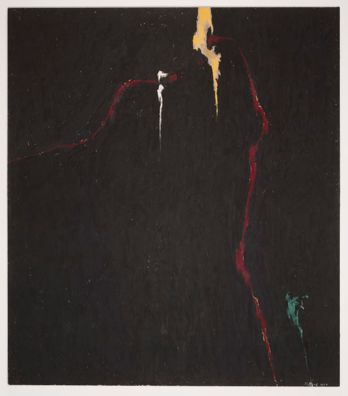

PH-235 (1944-N-No. 1), 1944, Oil on canvas, 268 x 234.9 cm, Clyfford Still Museum, Denver; 1.2011.570, © 2019 City & County of Denver, Courtesy Clyfford Still Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lifelines

Commentary by Harry O. Maier

Clyfford Still (1904–80) belonged to a circle of pioneering American Abstract Expressionists in New York City, which he abandoned to pursue an often- isolating practice of visual creation on a farm in Maryland. In Still’s work each line, colour, shape, and position takes on a Zen-like quality that is more than the sum of its elements.

PH-235 (1944-N-No.1)—one of a series executed over several years that Still intended to be viewed together—shows a broken rust line running up across and then down the canvas. White and yellow pull downward intersecting the red, and, like the vermillion at bottom right, end in a knifepoint, as though slashing through the black and often cracked impasto that dominates the canvas. Still called these ‘lifelines’ after farm-boy experiences from his childhood. His father would lower him, suspended by rope, into wells—usually to survey them but sometimes also as punishment.

‘Who will roll away the stone for us from the entrance of the tomb?’ Mark has the women continually ask one another on their early morning journey to Jesus’s grave to anoint his body (16:3). Mark says the sun had risen, but it is a dark and well-trodden path to the tomb. We all know what it is to come to the graveside in grief and broken hope, suffocated by the requirement to keep breathing. This is indeed a ‘very large stone’ (16:4).

Their question is, however, not the right one. The attentive reader of Mark’s Gospel will remember that Jesus has predicted three times, once plainly, that he will die and rise again (Mark 8:31–32; 9:31; 10:33–34). These predictions are lifelines. The better question is, ‘How are we going to live with resurrection?’ The women’s response is to flee in terror. Easter is like a gash that bleeds colour through the darkness in which they (as often we) are suspended. The initial path toward the finality of death is torn open like knife-edged rust, white, yellow, and vermillion to become a road whose end and whose beginning is resurrection.

Jean Dubuffet

The Road of Humankind, 1944, Oil on canvas, 129 x 96 cm, Museum Ludwig, Cologne; Gift of Ludwig, © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris; Photo: akg-images

‘There you will see him’

Commentary by Harry O. Maier

George Dubuffet (1901–85) coined the phrase art brut (‘raw art’, often called ‘outsider art’) to describe the rejection of the artistic canons of professional training in favour of promoting an artistic style free of cultural convention. Chalk scribbling on a sidewalk, children’s drawings, and images produced by the mentally ill inspired the artist, challenging conventional perception and inviting the mind 'to adjust to a new fragmentary and discontinuous perspective, and for it to decide to radically change its old operating procedures' (Dubuffet 1989: 42).

The painted canvas of Men on Road pushes beyond two- towards three-dimensionality. And it is at once a bird’s eye and straight-on view of a landscape. Dubuffet mixes a thick paste of oil and materials such as sand to create a bitumen surface on which he scratches fields and other details of the landscape and draws a childlike picture of travellers on a curving road, walking toward a house that threatens to drop off the edge of the flat horizon at the top. A man on a bike is smiling, his legs simultaneously on either side of the pedals; a cow’s teats (lower left) hang between impossible legs. Dubuffet’s carefully crafted view invites us to look again at the world around us, capturing a celebration of existence through an art whose ‘chaotic swarming … enriches and enlarges the world’ (Dubuffet 1989: 73).

The young man at the empty tomb promises that if the disciples go to Galilee they will see the raised Jesus there. In Matthew’s Gospel this is exactly what happens (28:16–20), but Mark does not furnish us with this ending. The women flee in terror and tell no one. So ends the Gospel in its oldest (shortest) version.

Or does it? One suggestion has been that the ending is an instruction to return to the start of the Gospel and reread it as a call to see Easter by living the resurrection amidst the ‘Galilees’ of our daily lives. Mark’s Easter story is not once upon a time, but always present. Where we are is where we will see him. Easter as ‘art brut’ asks us to open our eyes for the outsider’s perspective, from an empty tomb onto our daily lives.

References

Dubuffet, Jean. 1986. Asphyxiating Culture and Other Writings, Trans. by Carol Volk (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows)

Unknown artist

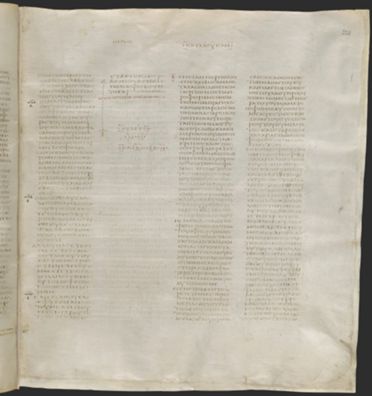

End of the Gospel of Mark, from the Codex Sinaiticus, Mid-4th century, Manuscript, The British Library, London; Quire 77, fol. 5r (BL folio: 228 scribe: D), Photo: © The British Library Board Quire 77

Mark’s Innumerable Endings

Commentary by Harry O. Maier

The fourth-century Codex Sinaiticus, named after its nineteenth-century discovery at St Catherine’s monastery in the Sinai desert, is the earliest, most complete version of the Gospel of Mark we possess. Sinaiticus’s original story ends anti-climactically with women fleeing the scene and in their silence disobeying the command to tell others. There are longer versions, but their endings were added later, and stylistic comparison with the rest of the Gospel suggests they were created by different writers.

The Codex’s ending concludes the Gospel with the adverb gar (‘for’), which would be like ending an English sentence with the word, ‘because’. So, is this earliest version of Mark a witness to a mutilated Gospel, a text whose first and original conclusion has been torn away? In the Codex’s closest sibling, the contemporaneous fourth-century Codex Vaticanus, the Gospel ends identically. Perhaps earlier versions of the same ending motivated scribes to produce their own final account. On the page reproduced here in the space under the second column a second hand has added in abbreviated form, ‘the Gospel of Mark’.

Whatever the author of Mark’s Gospel intended (whether this or another ending), the manuscript has taken on a life of its own. The scribe recorded here has added his own words, others more of them. The creators of the Codex have added to Mark’s Gospel in a different way, by incorporating the written words of its text into a collection of writings as costly to produce as it is magnificent. They have thereby transformed its poor Greek and its surprise ending into a material object incongruent with its probable historical origins. The words have been transformed into a beautiful material artefact of ink and leather.

Perhaps we might see that empty column as an invitation to complete the resurrection story, doing what the women failed to. For Mark has this to say: wherever the raised Jesus may be, he is not here on this page—not at this (lost?) ending, nor amidst the longer ones. Could it be that he is there waiting in the empty column for us to create an Easter ending in our own response to the young man’s command at the tomb? To go to Galilee to our own resurrection story?

Clyfford Still :

PH-235 (1944-N-No. 1), 1944 , Oil on canvas

Jean Dubuffet :

The Road of Humankind, 1944 , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist :

End of the Gospel of Mark, from the Codex Sinaiticus, Mid-4th century , Manuscript

On the Open Road to Galilee

Comparative commentary by Harry O. Maier

Mark’s ending is puzzling. At no time do we actually see the raised Jesus. There is a strange absence of a resurrection in a Gospel that has promised three times that Jesus will rise from the dead (8:31; 9:30; 10:32–34).

Some scholars argue that there never was a resurrection appearance in Mark’s Gospel. Others counter that the report has simply been lost. Both can point to the earliest extant versions of Mark, one of them the fourth-century Codex Sinaiticus, where the sentence about the women fleeing ends the Gospel. Everyone notes it concludes with an adverb that usually indicates material that is to follow; some observe that Mark’s Greek is especially bad and that here he is being ungrammatical. As any good Bible translation indicates, later scribes furnished their own endings (which modern editions set off from verse 8 or include in a footnote). The authors of Matthew and Luke recorded their own separate resurrection appearances. Nobody knows what Mark intended; authors die and the texts they leave behind take on lives of their own.

The women may not have told anyone (v.8), but someone did, otherwise there would be no Gospel of Mark. The priceless Codex Sinaiticus is testament. After the last line with the terrified women it teases us with an empty column following its inconclusive conclusion. Perhaps we should interpret that space as an invitation to look to other places to find Mark’s real ending. The raised Jesus has gone ahead to Galilee (v.7). Jesus in Mark’s Gospel is always ahead: Jesus commands Peter like Satan to get behind him (8:33); disciples take up their cross to follow him (8:34); Jesus is ahead of the disciples as they travel through Galilee to Jerusalem (10:32). Now they are to get on the road once again, where he is ahead once again. One interpretation is that the ending of Mark’s Gospel is an instruction to go back to chapter one, where the story begins with Jesus himself going into Galilee (1:14), and to see him as the Easter Jesus incognito, with the journey to crucifixion as the path of Easter discipleship. The entirety of Mark’s Gospel should thus be read paradoxically as a sixteen-chapter-long resurrection story. In Mark’s Gospel, the raised Jesus is hidden in plain sight.

How else might we interpret Mark’s ending? One role of artists is to give us eyes to see what we could not otherwise behold or to prompt us to look beyond our conventional ways of seeing with new perspective. Mark with his untutored Greek is like that kind of artist. The art brut movement inaugurated by Jean Dubuffet in the 1940s asks that we attend to perspectives given outside the educated establishment, such as those of children and the mentally ill, to learn to see the world around us afresh and to apprehend what we cannot see so long as our eyes are wide shut.

These artists offer unconventional views and perspectives. In Clyfford Still’s PH-235, suspended lifelines tear away the black and intersect with a broken rust line that at times tentatively crosses the canvas. In Dubuffet’s Men on a Road, textured figures somewhere between two- and three-dimensionality populate, walk, or ride along a multi-coloured road that traverses fields enlivened by blue, green, and yellow, toward a blue and red-hued house situated on the edge of a horizon, an otherwise unknown destination, its entry centred at the top of the road both as an end and an invitation. ‘All roads lead to absurdity and impossibility if we imagine them to be linear’, remarks Dubuffet (1989: 73) in his call to live the vitality his painting commends. ‘There will be no more viewers in my city, only actors’, he announces in his art brut manifesto (1989: 72).

It requires attention and patience to receive these revelations. Like Mark’s Gospel they invite a journey where we learn to see the everyday with new eyes. Perhaps one may even detect the faint outline of a crucified man promising Easter vision if we come and follow.

References

Dubuffet, Jean. 1986. Asphyxiating Culture and Other Writings, Trans. by Carol Volk (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows)

Commentaries by Harry O. Maier