Genesis 7

Noah’s Flood

Works of art by Jacopo Bassano, Michael Wolgemut, Wilhelm Pleydenwurff and William de Brailes

Jacopo Bassano

The Flood, c. 1570, Oil on canvas, 201.0 x 260.5 cm, The Royal Collection Trust; RCIN 406106, Royal Collection Trust / ©️ His Majesty King Charles III 2023

Desperation in Demand

Commentary by Anna Somers Cocks OBE

This is a scene of desperation, of people and animals trying to save themselves. But they are all doomed. The ark is hardly visible mid-right in the stormy gloom (all the gloomier because the painting has darkened and degraded over time). A horseman is galloping towards it, but he’s not Noah. It is possible that the man emerging from the house is our hero, but his family and the pairs of animals are nowhere to be seen. Perhaps the Lord has already shut them in.

Like William de Brailes’s miniature painting of 1250, this is about the horror of the flood itself.

In the 1560s, Jacopo Bassano (c.1510–92) began to paint more and more Old Testament subjects under the influence of Reformation ideas. For, a huge change was taking place in the religious practices of Europe as lay people challenged the authority of the Roman Church and demanded to have access to the New Testament, and especially the Old Testament, in a language that they could understand, rather than Latin, known mainly by the clergy.

The Catholic Church’s reaction to this revolt was the Council of Trent (1545–63) and one of the ideas it emphasized was that Noah was the saviour of humanity, a precursor of Jesus Christ. But there may have been another reason for the subject’s popularity. Pietro Aretino (1492–1556), the famous, openly gay playwright and erotic poet, translated Genesis into Italian (published Venice, 1538), adding embellishments from his own imagination, with a particularly dramatic evocation of the Flood.

Jacopo Bassano liked to fill his foregrounds with rustic life and animals, tucking away the actual subject of the painting in the background. Here, he adapted this formula to the story of the Flood, and the action and drama are remarkably close to Aretino’s description of the scene. Jacopo may also have been aware of the great flood of 1560, when the river running through Feltre, less than a day’s ride from Bassano, broke its banks with great loss of life.

Jacopo and his workshop painted the story of Noah’s Flood repeatedly from the 1570s onwards. Indeed, they produced more of their four-part Flood series than any other Old Testament scene. This version is from a series commissioned by Guglielmo Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, then sold to King Charles I of England (1600–49), which is how it comes to be in the Royal Collections today.

References

Aikema, Bernard. 1996. Jacopo Bassano and his Public Moralizing Pictures in an Age of Reform ca.1535–1600 (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Aretino, Pietro. 1538. Il Genesi di M. Pietro Aretino con la Visione di Noè ne la quale vede i misterii del Testamento Vecchio e del Nuovo, diviso in Tre Parti (Venice: Francesco Marcolini), available at https://books.google.it/books?id=KONfAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb&#v=onepage&q&f=false

Brown, Beverley Louise and Marini Paola (eds). 1993. Jacopo Bassano c.1510–1592 (Fort Worth: Kimbell Art Museum)

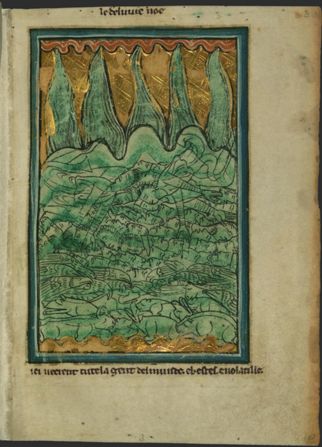

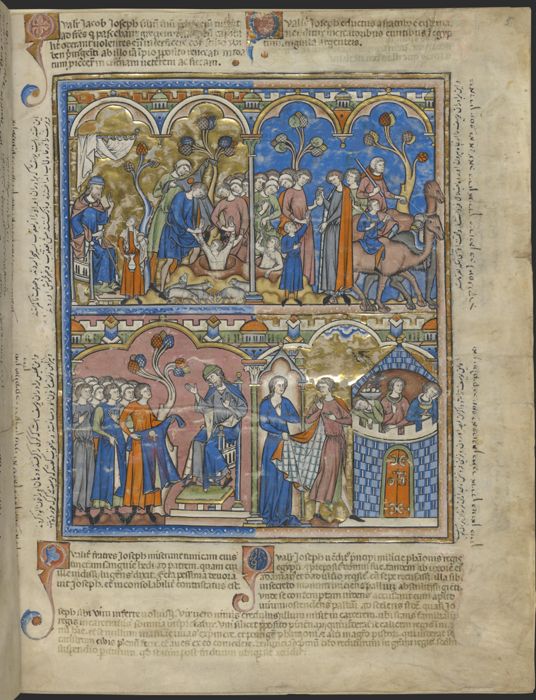

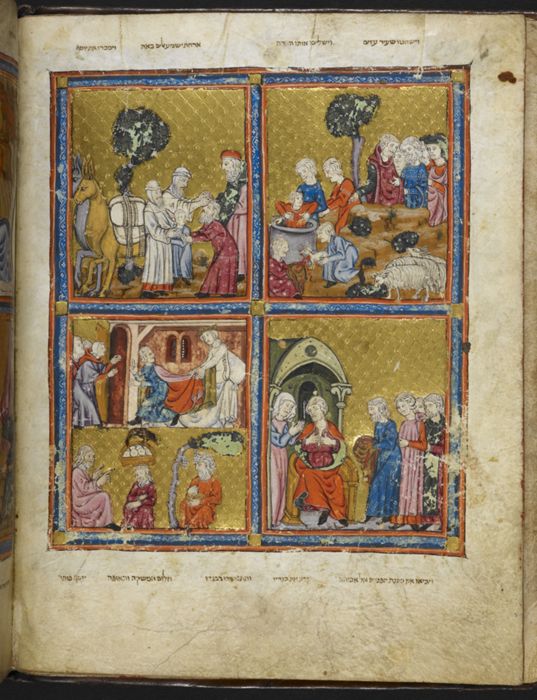

William de Brailes

The Flood of Noah, leaf from Bible Pictures, c.1250, Illuminated manuscript, 132 x 95 mm, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore; W.106.2R, The Walters Art Museum

Not All Aboard

Commentary by Anna Somers Cocks OBE

The animals went in two by two, hurrah, hurrah

The elephant and the kangaroo, hurrah, hurrah…

…and, as we know, jolly old Noah saves all the species from the flood with his ark.

Actually, there was nothing jolly about it at all. It was terrifying, with God so disappointed by humanity’s behaviour that He decided to destroy His own creation.

This is how the thirteenth-century English miniature painter William de Brailes imagined the devastation. The animals are innocent but they have died too because, as the fourth-century theologian John Chrysostom explains—following the Jewish commentators—they were created for humankind’s sake; therefore, it is right that they too should meet their end. God has broken the dome that according to medieval cosmology was the sky, separating the waters ‘above the firmament’ from the waters below, so the ocean above is pouring down in five cataracts.

In the Middle Ages, artists nearly always followed established prototypes, rarely deviating from them much or painting from reality. Here we have an extraordinarily original full-page painting, about the size of a paperback, with an underwater view of the Flood. The remarkable detail is the way in which the human bodies are floating on their fronts with their arms hanging down; de Brailes must have seen this in real life because that is how a corpse actually floats under water. We know that he was a bit of an individualist because he signed his work twice at a time when most artists remained anonymous, and his spirited scenes often break through the margins of his pictures.

He lived in Oxford, when the university was growing fast. The increasing numbers of religious scholars—combined with the Church’s new emphasis on personal devotion—led to demand for smaller prayer books for private clients. It was the age of the psalter, a prayer book with a selection of psalms prayed eight times a day, often preceded by pages illustrating stories from the Bible. This is one of 24 leaves in Baltimore, from a psalter now in the Stockholm National Museum [Ms. B.2010]. There are seven more leaves in Paris, and there may originally have been as many as 98.

With its piled up dead bodies this image was intended to shock, displaying the effects of humankind’s sinfulness, before the reader turned the page and saw the ark in which God decided to give creation another chance.

References

De Hamel, Christopher. 2001. The Book: A History of the Bible (New York: Phaidon)

Hill, Robert C. (trans.). 1990. John Chrysostom Homilies on Genesis 25:18–45, Fathers of the Church 82 (Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press)

Kauffman C.M. 2003. Biblical Imagery in Medieval England 700–1500 (London: Harvey Miller)

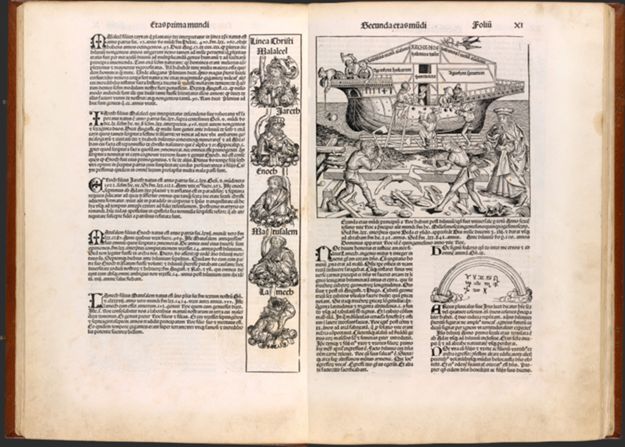

Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff

The Construction of Noah's Ark, from Die Schedlsche Weltchronik (Registrum huius Operis libri cronicarum cumfiguris et ymagibus ab inicio mundi) by Hartmann Schedel, 1493, Woodcut print, Sheet: 460 x 314 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Rogers Fund, 1906, transferred from the Library, 21.36.145, www.metmuseum.org

Down to Earth, though Made to Float

Commentary by Anna Somers Cocks OBE

Make yourself an ark of gopher wood; make rooms in the ark and cover it inside and out with pitch.… Make a roof for the ark, and finish it to a cubit above; and set the door of the ark in its side; make it with lower, second, and third decks. (Genesis 6:14, 16)

This woodcut does not pay as much attention to the Lord’s building instructions as modern biblical literalists do. Yes, the ark has three floors, but it is a standard cog such as sailed the North Sea throughout the Middle Ages, not a massive ship 525 feet (160m) long, which is what you get if you multiply the length of the Egyptian cubit, 21 inches (53cm), by 300.

This image is one of 1,809 produced by Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff for the Schedelsche Weltchronik (world chronicle), published in Nürnberg in 1493.

Noah, dressed as a rich Nürnberg merchant of the day, is directing the work, with craftsmen who presumably do not know that they are about to perish. The superstructure is helpfully labelled. The central roof space is the living quarters for Noah and his family, with the animals on either side. The window in the middle of the next deck is the ‘Stercoraria’, for shovelling out manure, etc. The herbal and animal-parts apothecaries on either side were probably stipulated by the chronicle’s author, Hartmann Schedel, who was a doctor of medicine.

This is not so much a religious image as an illustration—within a history of the world—of a story so familiar and domesticated that the artist could depict it as a contemporary boatyard, as much about carpentry as the Bible story. He hints at the rest of the story by depicting the dove with the twig in its beak, which is arriving prematurely top right.

The image comes out of the same cultural stable as late medieval satirical but moralizing plays based on stories from the Old and New Testament, with stock characters such as Noah’s wilful wife, who refuses to get into the ark because she prefers to drink with her girl friends. Needless to say, the menfolk prevail; Noah’s sons drag her into the ark and the gossips all drown.

References

Füssel, Stephan (ed.). 2001. Schedelsche Weltchronik (Cologne: Taschen)

Pollard, Alfred. 1909. English Miracle Plays, Moralities, and Interludes (Oxford: OUP)

Jacopo Bassano :

The Flood, c. 1570 , Oil on canvas

William de Brailes :

The Flood of Noah, leaf from Bible Pictures, c.1250 , Illuminated manuscript

Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff :

The Construction of Noah's Ark, from Die Schedlsche Weltchronik (Registrum huius Operis libri cronicarum cumfiguris et ymagibus ab inicio mundi) by Hartmann Schedel, 1493 , Woodcut print

The Days of Noah Yet to Come

Comparative commentary by Anna Somers Cocks OBE

The story of Noah and the Flood was, and still is, one of the best known in the Old Testament and it has been depicted with great imagination over the centuries. Three hundred years separate the first image in this exhibition—a miniature painting of corpses under water by Walter de Brailes, about 1260—from the large and theatrical oil painting of about 1584 by Jacopo Bassano—a painter in the Venetian tradition—of desperate people trying to save themselves. In between comes the precise, late Gothic woodcut in the Schedelsche Weltchronik (1493), from the South German artist Michael Wolgemut’s workshop, representing Noah as a prosperous ship builder directing the construction of the ark.

One can only make an informed guess at what thoughts these three artists had in their heads about the story, but it is safe to say that they would all have considered the Bible to be actual history, in which Noah’s Flood was an important event. This is because, by ancient tradition, it ended the first chapter of existence after the Creation (the next six chapters in the Schedelsche Weltchronik being the period until the birth of Abraham; the period up to the birth of King David; the period until the Babylonian exile; the period up to the birth of Christ; and then all of time thereafter, with the second coming of Christ as the last chapter).

It is also safe to say that they would have been familiar with how the story related to the second coming, because these words from the Gospel of Matthew have always been read at religious services in the season of Advent, which remembers both the first coming of Christ at Christmas, and anticipates His final return:

Jesus said to his disciples: ‘As were the days of Noah, so will be the coming of the Son of man. For as in those days before the flood they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, until the day when Noah entered the ark and they did not know until the flood came and swept them all away, so will be the coming of the Son of man’. (Matthew 24: 37–39)

In other words, the flood is a warning to be ready for the end of days.

It is not so likely that the artists mastered the finer points of theological interpretation of Noah’s Flood, but it is certain that they would have been accustomed to looking beyond the bald facts of the Bible to allegorical and moral meanings because that was an intrinsic part of a Christian mindset even in the later sixteenth century. They would not have sat around like Bible literalists of today puzzling over how all the world’s animals fitted into the ark (even if it was as long as a football field).

For, as St John Chrysostom wrote in his delightfully down-to-earth homilies on Genesis in the fourth century, we should not speculate on how smelly it must have been in the ark, where they got their drinking water, or why Noah was not eaten by the lions, because we should not question the actions of God with human reason.

Thus, during the Middle Ages and beyond, the salvation of Noah with his family and the animals was seen as proof of God’s justice and mercy, while the ark itself was considered a symbol prefiguring the Church as the community in which everybody would find salvation. The moral message for the individual was that we need to live virtuously and obey God, just as Noah lived virtuously and obeyed God’s instructions, however mad they may have seemed to him.

But the key message of Noah’s Flood was that God said He would not destroy the world again. For us today, the message—if we continue to think allegorically—is that creation was entrusted to humankind and we are responsible for it. Noah is all of us and we can still save ourselves. Each of us has to build an ark against the chaos, the flood of today. The ark is a microcosm of the whole world.

References

Hill, Robert C. (trans.). 1990. John Chrysostom Homilies on Genesis 25:18–45, The Fathers of the Church 82 (Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press)

Commentaries by Anna Somers Cocks OBE