Luke 18:9–14

The Pharisee and the Tax Collector

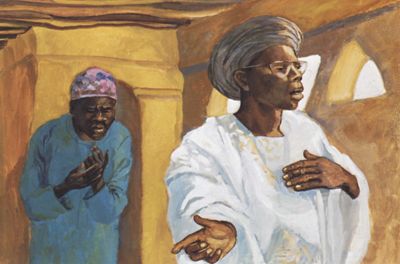

Jesus Mafa Project

The Pharisee and the Publican, 1973, Painting, Current location unknown; © MAFA Editions de l'Emmanuel (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 )creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

The Taxpayer and the Tax Agent

Commentary by Ellen T. Charry

The Life of Jesus Mafa was a Roman Catholic missionary project in the 1970s that aimed to teach the gospel to inhabitants of Northern Cameroon, and help them relate it to their daily lives. François Vidil worked with Mafa Christian communities (who dressed up and enacted the scenes) to create an extensive series of paintings depicting Jesus and other New Testament characters as contemporary Africans.

We are shown a simple building with two men in it—one foregrounded, one backgrounded, both facing forward. The man in the foreground can be read as a ‘take-charge’ type. His eyeglasses may suggest intelligence, education, and privilege. He is dressed in white. Speaking to an implied audience to his left (outside the painted composition), he seems authoritative—pointing with his right hand as he places his left hand over his heart; referring to himself perhaps. He is the pharisee of Luke 18.

Standing at distance behind him is the other man in the story. He is dressed in blue, his shoulders stooping forward, his face contorted as he looks down at his plaintively cupped palms.

The artist has taken a liberty with the text, which has both men standing apart from each other and in prayer. They are not interacting with others. But this artist has the pharisee speaking to a nearby auditor or auditors. He seems an upstanding citizen and to know what he is doing.

And there is no harm in that, is there? That is Luke’s penetrating question. The pharisee pays his taxes. The collector carries them to their destination. Who wants to pay taxes to an oppressive occupier after all? Perhaps there were some dishonest tax agents on top of all that who earned them the double opprobrium of the populace, but in what governmental office is there no corruption?

Phariseeism is a method of scriptural interpretation. Collecting taxes is a livelihood—in this case, on behalf of a hated occupier. Comparing them is inane, or rather impossible. Perhaps the tax collector is also a pharisee. We do not know. But we do know that the one who pays taxes and the one who collects them from him are both working to prevent violence during a hated occupation with bloodshed being but a touch away. Who is to condemn either?

Unknown artist

Ecclesia and Synagoga, from the south transept portal of Strasbourg Cathedral, c.1230s, Stone, Musée de l’Oeuvre Notre-Dame, Strasbourg; Photo: Musées de Strasbourg, M. Bertola, Courtesy Musée de l’œuvre Notre Dame de Strasbourg

Ecclesia and Synagoga

Commentary by Ellen T. Charry

Medieval statues of Ecclesia and Synagoga (the Church and the Synagogue) tell the reception history of texts like Luke 18:9–14 which were interpreted as contrasting the penitent Christian with the proud Jew.

This pair was carved for the exterior of Strasbourg Cathedral, c.1235. Another pair is over the portico of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, c.1240. Comparably supersessionist imagery in many other artistic media has also functioned historically to convey the triumph of the Church over the Synagogue. Some of it is grotesque, as when Jews were depicted as demons. They tell us something of where Luke’s story about a supposedly self-righteous man—and others like it (e.g., Matthew 6)—led a self-righteous Church.

In these sculptures, Church and Synagogue are personified as attractive women. At Strasbourg, the Ecclesia is beautiful in her crown, her long flowing locks cascading over her shoulders, her cloak clasped by a fine brooch. Her right hand holds the stanchion of the church whose cross reaches above her head. Her left hand cradles a chalice to her body. She seems confident, looking slightly inquiringly down her nose at the Synagoga to her left.

This other woman, by contrast, is bareheaded, blindfolded, her head lowered and looking toward her left—away from the Church’s gaze. Her left arm extends downwards, its fingers—also extended downwards—barely retaining their hold on her Torah book. Her right hand holds the bottom half of a lance broken into four parts, its top leaning against her shoulder.

The two figures seem well aware of one another, one confidently watching, the other shamed as she is watched. Triumphant Christian pride and defeated Jewish shame teach those in the cathedral’s precincts what they need to know about Christianity and Judaism.

The text of Luke 18:9–14 intends to teach the reverse of the message in the sculptures, however. Humility is morally superior to self-confidence, and contempt is to be chastised. Yet the Church came to pride itself on this point. The tax collector and the pharisee came to represent the Church and the Synagogue as depicted by the sculptures rather than as the text would have it. Humility became a foundation of pride and shaming was prided.

It’s a catch-22. The Church is hoisted by its own petard as it proudly preaches about humility. This may not have been Luke’s intention, but it was the result.

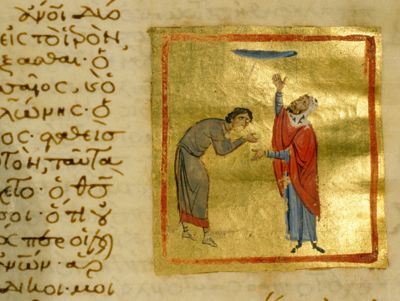

Unknown artist

The Pharisee and the Publican, from Tetraevangelion, 12th century, Manuscript illumination, 220 x 150 mm [page], The National Library, Athens, Greece; Codex 93, fol. 127v, Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Beseeching and Reaching

Commentary by Ellen T. Charry

This Byzantine manuscript illumination does away with the narrative setting, props, and staging of Luke’s story. We simply have two figures against a gold ground. The colourfully dressed pharisee lifts his gaze and extends his right arm towards a heavenly opening above him. His left arm is extended as if in invitation towards his companion. The tax collector is drably dressed, bent in half to suggest his humility, and without a head covering.

Contrary to the text, in which each man keeps to himself—perhaps even unaware that the other is in the building—here, the men face each other. The penitent’s plaintive eyes look up to the uplifted face of the pharisee and he reaches toward the pharisee’s extended hand. Although their hands do not meet, the energy in the composition flows from left to right then upwards, from the bent penitential back of the tax collector through his outstretched hand to the other man’s upwardly extending body and arm and finally to the opening above him.

Thus, unlike in Luke’s text, the figures facing each other are shown in relationship. The pharisee beseeching heaven seems to be sending the penitent’s prayers aloft as the priestly conduit of contrition.

Triumph and shame defy colourization. The one reaching to heaven is not an exemplification of the disgraced Synagogue as he was so frequently in the church-sponsored works of later artists. The agonized penitent is not the triumphant Church that the Strasbourg sculptor carved for his cathedral. The artist seems to have turned Luke around.

Jesus Mafa Project :

The Pharisee and the Publican, 1973 , Painting

Unknown artist :

Ecclesia and Synagoga, from the south transept portal of Strasbourg Cathedral, c.1230s , Stone

Unknown artist :

The Pharisee and the Publican, from Tetraevangelion, 12th century , Manuscript illumination

Contempt, Contrition, Care

Comparative commentary by Ellen T. Charry

Luke’s story of the pharisee and the tax-collector may be one of the most popular preaching texts in the Christian Bible, but it is not an easy text. The artworks in this exhibition span three continents and nearly a millennium. They show how Luke’s story, intended to castigate contempt has, in no small way, taught contempt for Jews and Judaism. They also show some ways in which that reading might be repaired.

The story and its sculpted heir(esses) constitute a twisting and twisted story of contempt. Under Roman occupation, the general populace, here represented by the pharisee, held tax collectors in contempt. Jesus’s story is Luke’s way of turning that contempt on its head in Jesus’s name, as he (Luke) says in his introduction to it (18:9).

Luke’s lesson to his readers to hold the pharisee in contempt instead of the Roman employee presents itself as an imitation of Jesus. Jesus’s closing admonition at verse 14b says (in yet another reversal of social convention) that the last and first will change places (Matthew 19:30; 20:16; Mark 10:31). In relating this story, Luke reverses the object and subject of contempt in similar vein. But he does not criticize contempt itself.

Three daily morning thanksgivings that are still part of every Jewish prayer book thank God that the pray-er is not a pagan, a slave, or a woman. (In various later editions of such books these have been revised to emphasize what is being positively affirmed and to set aside the negative contrasts through which the affirmations are made.) Luke ridicules and distorts these thanksgivings, placing them as contemptuous words in the pharisee’s heart.

Paul also objected to these thanksgivings (they are in the subtext of Galatians 3:28) echoing them in the order in which they appear in the prayer book. But Paul does not deride them; he simply does away with the apartness that the thanksgivings cultivate. Both Paul and Luke were interested in Gentiles, but angry ridicule and contempt belong to Luke.

Perhaps it was inevitable that the oppositional first–last reversal should result in the very contempt the story intended to criticize but with different occupants in the respective seats. Reversal of convention begins in Genesis and is pervasive in Paul. We see it here in Luke. Unfortunately, the Church chose to carve it in stone against the Jews. The personified figures of Church (Ecclesia) and Synagogue (Synagoga) on the façade of Strasbourg Cathedral are paradigms of this divisive and pervasive tendency in Western Christian art. It is a road all too well travelled.

The Byzantine illuminator and the twentieth-century painter whose work we see here suggest that history did not have to go that way. Our Byzantine illuminator takes the road less travelled. The Pharisee’s arms extended in an ‘L’ shape (facing left) suggest that repentance and prayer work together. The one weakened by sin is so distraught that he needs his currently stronger neighbour to send his prayers aloft. The Pharisee, perhaps knowing that he will be the morally needy one at some future time, prays on his chagrined companion’s behalf. Contempt can be painted out of this text and care read in.

The painting made in Cameroon as part of the Life of Jesus Mafa project is ambiguous. It can certainly sustain the conventional interpretation of the text about the self-justifying pharisee. But, viewed alongside the Byzantine illumination, this work may also allow an opening for us to ‘read care’ into it (as we may into the text of Luke). What if this were a court of law or perhaps of public opinion, with the pharisee functioning as an attorney for the defendant standing behind him? Perhaps the defendant lacks the articulacy needed even to sort through the painful thoughts and emotions that confuse him. No one should ever represent themselves in a court of law or even of public opinion. The competent pharisee may be indicating that he has the authority and information needed to speak on the defendant’s behalf. Relocating the biblical story to a contemporary setting, the Jesus Mafa project ensures that we ask these questions not only of characters in an ancient story, but of ourselves. However much like the pharisee of Luke 18 we are, there may be redemptive choices for us. It will depend on how we use our voices, who we speak to (and for), and what we say.

A realistic theology will hold that everyone can and indeed will likely sit in all the seats available in this story: the penitent too chagrined to beseech, the self-righteous citizen looking down on others, the caretaker of neighbours, and the neighbours needing care. If contempt is in the eye of the viewer, may not care also be found there?

References

Doran, Robert. 2007. ‘The Pharisee and the Tax Collector: An Agonistic Story’, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly, 69.2: 259–70

Friedrichsen, Timothy A. 2005. ‘The Temple, a Pharisee, a Tax Collector, and the Kingdom of God: Rereading a Jesus Parable (Luke 18:10–14a)’, Journal of Biblical Literature, 124.1: 89–119

Holmgren, Fredrick Carlson. 1994. ‘The Pharisee and the Tax Collector: Luke 18:9–14 and Deuteronomy 26:1–15’, Interpretation, 48.3: 252–61

Commentaries by Ellen T. Charry