Matthew 27:37; Mark 15:26; Luke 23:38; John 19:19-22

Reinscribing The Cross

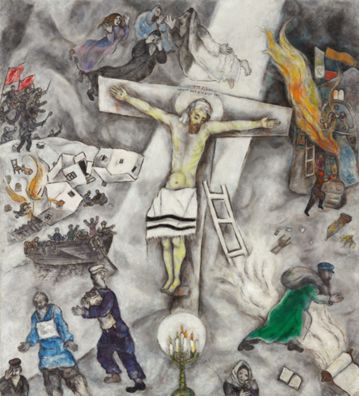

Marc Chagall

White Crucifixion, 1938, Oil on canvas, 154.6 x 140 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Alfred S. Alschuler; 1946.925, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris; The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY

The Jewish Jesus

Commentary by Amitai Mendelsohn

The year before the outbreak of the Second World War, Jewish artist Marc Chagall explicitly portrayed Jesus as an emblem of Jewish suffering. Surrounding the cross in White Crucifixion, 1938, we see Jews under threat in scenes of attack, destruction, and flight.

White Crucifixion was painted in the context of synagogue-burnings in Munich and Nuremberg in the summer of 1938, the expulsion of Polish Jews living in Germany that October, and finally the pogrom of November 1938—Kristallnacht (The Night of Broken Glass)—a foreshadowing of what would occur in Europe when war broke out. Chagall’s decision to create a large picture rather than, say, an intimate drawing was influenced by the paintings of German anti-Fascist artists who had already emphasized Jesus’s Jewishness, but his main source of encouragement was more local. French support for this emphasis had grown following the publication in 1937 of a book by the French Jesuit Joseph Bonsirven—The Jews and Jesus—a book which used modern historical scholarship to reassert Jesus’s Jewishness. Bonsirven cited the famous words of Israel Zangwill from his 1892 novel Children of the Ghetto: ‘the people of Christ has been the Christ of peoples’.

Chagall was extremely aware of his target audience. Feeling that the Jews did not need to be told about the difficulty of their situation—they were experiencing it personally—he therefore sought the most effective way to bring Jewish suffering to the attention of Christians. Thus he chose to invest the crucifixion, their most distinctive and most profound image, with Jewish content. He believed that Christians would understand the message of Jesus’s Jewishness from the prayer shawl girding his loins, the menorah surrounded by a halo of light that echoes Jesus’s halo, and the shtetl scenes of persecution. Above the cross, Chagall reproduced the words said to be on Pilate’s placard in John 19:19—‘Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews’. He did so in Aramaic: the language that Jesus, like most Jews of his day, probably spoke.

Many years later, Chagall’s approach proved more successful than the artist might have expected: Pope Francis I spoke of his affinity for this Jewish portrayal of Jesus and called White Crucifixion his favourite painting.

Igael Tumarkin

Bedouin Crucifixion, 1982, Steel and mixed media, 211 x 206 x 80 cm, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Gift of the artist, B82.0426, © Igael Tumarkin; Courtesy of The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Whose Crucifixion?

Commentary by Amitai Mendelsohn

In Bedouin Crucifixion, Igael Tumarkin (born 1933), an influential Israeli artist, demonstrated his empathy with Bedouins struggling against government-sponsored evictions and land confiscations.

There is no placard. Instead, we must discern who is ‘on the cross’ here through material objects with strong associations and resonances.

The hybrid cross Tumarkin constructed consists of horizontal wooden branches—used by the Bedouin, a traditionally nomadic people, as tent-poles—and an industrial iron vertical backdrop against which a soft assemblage of pieces of cloth and other organic materials is ‘crucified’. The rigid metal structure seems to symbolize the callous Israeli establishment that victimizes the poor and the helpless, in this case the Bedouins.

One of Tumarkin’s most important sources of artistic influence was the renowned Isenheim Altarpiece (1512–16) painted by Matthias Grünewald and asserting Christ’s radical solidarity with the victims of ergotism (a disease caused by infected rye).

In Bedouin Crucifixion, the spare wooden branches recall the emaciated arms of the Isenheim Christ and, along with the bowed tree-stump head, recreate something of the gaunt horror of Grünewald’s depiction. But here a different solidarity is asserted, and the title of the work itself does the job of Pilate’s placard.

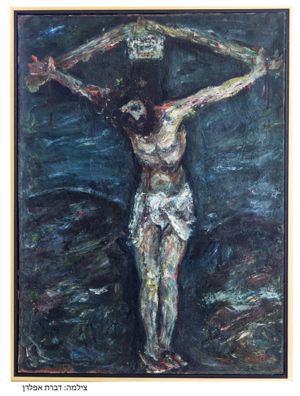

Moshe Castel

Untitled (The Crucified), c.1948, Oil on canvas, 72 x 53 cm, The Moshe Castel Museum of Art, Ma’ale Adumim; © The estate of the artist; Photo: The Moshe Castel Museum of Art / Dovrat Alpern

I in Him

Commentary by Amitai Mendelsohn

The story behind this dark crucifixion by Moshe Castel (1900–91), an Israeli artist known for his depictions of Jewish religious, local, and national subjects, must be sought in Castel’s personal history. The work was created when the artist secluded himself in a monastery near the Sea of Galilee in order to recover from the loss of his first wife, who died in childbirth, and the death of their daughter three years later. Discovered in a locked cupboard in Castel’s house after his death in 1992, the painting—which is highly unusual in the context of his work and that of his Israeli contemporaries—was displayed publicly for the first time in the 2017 exhibition Behold the Man: Jesus in Israeli Art, curated by Amitai Mendelsohn at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

In an expressive style influenced by the French–Russian painter Chaim Soutine, and inspired by Marc Chagall’s crucifixions, Castel put himself on the cross. The face is a self-portrait, while above the figure a Hebrew inscription says ‘Castel the Jew’, so that the artist’s intense outpouring of pain culminates in total identification with the suffering of the crucified Christ.

In two of Castel’s sketches on this theme from the same period, the Hebrew inscriptions above the figure read ‘Jesus’ and ‘Jesus of Nazareth’. They give the full name Yeshu’a rather than the more common Yeshu, which was often read derisively by Jews as an acronym for a Hebrew phrase meaning ‘may his name be obliterated’ (Steinmetz 2005: 39).

The painter’s choice of name may indicate his rejection of this traditional revulsion and his own positive perception of Jesus as a personal and intimate symbol for suffering.

References

Steinmetz, Sol. 2005. Dictionary of Jewish Usage: A Guide to the Use of Jewish Terms (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield)

Marc Chagall :

White Crucifixion, 1938 , Oil on canvas

Igael Tumarkin :

Bedouin Crucifixion, 1982 , Steel and mixed media

Moshe Castel :

Untitled (The Crucified), c.1948 , Oil on canvas

A Polyphonic Placard

Comparative commentary by Amitai Mendelsohn

All four Gospels record the fact that an inscription was written on a placard and placed above Jesus’s head on the cross. They seem to be in full agreement on its importance even though they differ on the placard’s precise wording.

Matthew (27:37) and Mark (15:26) describe it as a record of the ‘charge against him’ (though in its brevity it reads ambiguously more like a description than a charge): ‘This is Jesus the King of the Jews’ (Matthew 27:37); ‘The King of the Jews’ (Mark 15:26). Luke refers to it as an inscription, and the wording is slightly different again: ‘This is the King of the Jews’ (Luke 23:38).

John, like Luke, does not use the word ‘charge’ (aitia)—it is called simply a ‘title’ (titlos)—and attributes the placard to Pontius Pilate. He offers a fourth form of the wording: ‘Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews’ (John 19:19), and adds that it was written in three languages: Hebrew, Greek, and Latin. In visual depictions of the crucifixion, this title frequently appears in contracted form as INRI (the first letter of each of the words in their Latin form).

The cross therefore speaks ‘multiply’ through its ‘title’—not only in different versions, but also in different languages.

The connection between the three works presented in this exhibition may be the crucified figure of Jesus but each one takes the story of the crucifixion down a different path. The artists extend the ‘polyphony’ of the placard, and of the cross itself, reopening the question of who we may expect (or be surprised) to find crucified before us.

Marc Chagall’s work is a cry against anti-Semitism—using the ultimate image of the suffering Jesus, and portraying him as a Jew in the midst of the anti-Semitic attacks on Jews that preceded the Holocaust. He subverts the ecclesiastical convention of an abbreviated INRI by reproducing the words of the placard in full, and he subverts John’s account (and perhaps Pilate too) by rendering them in Aramaic: Yeshu ha-notzri malka dihuda’ei—making the placard even more many-voiced than it was before. His intention was to return viewers to a sense of Jesus’s historical Jewishness, since the prevailing language among Jews in the Second Temple period was Aramaic.

Moshe Castel’s piece is a personal one—taking the image of the Crucified at a personal level and using it in his time of deep sorrow at the loss of his loved ones. A few years after the Holocaust, and in the same year that the State of Israel was inaugurated, his work takes the figure of Jesus to a solely personal realm. The inscription above his cross—‘Castel the Jew’—refers to the original inscription according to the Gospels, but with a significant change: the artist’s name replaces that of Jesus.

Igael Tumarkin’s Bedouin Crucifixion is a political statement about the Israeli authorities and their unfair treatment of the weak Bedouin culture. The wheel has turned—from being a symbol of Jewish suffering, the crucifixion is now a symbol of the Bedouin society under Israeli control. Harnessing the way that the Christian image of the crucifixion has become an almost universal symbol of ultimate sacrifice, Tumarkin makes a sharp political statement.

The Jesuit Joseph Bonsirven, who influenced Chagall, observed that for Jews the cross is not ‘the symbol of a self-sacrificing love, nor the sign of a redeeming hope, nor an emblem of peace, but the symbol of persecution, oppression, discrimination’. This may help us to understand how these three works came to be made by Jewish artists, each of whom had a deep connection to the suffering figure of Jesus and found their own meanings in it: collective, personal, and political—and perhaps also universal.

Commentaries by Amitai Mendelsohn