Deuteronomy 8

Remember, Do Not Forget

Lynn Aldrich

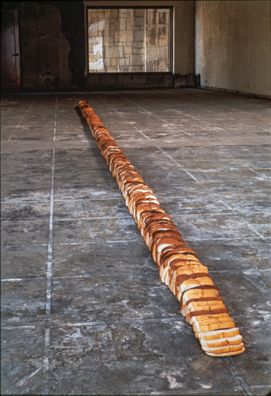

Bread Line, 1991, Bread; © Lynn Aldrich, Courtesy of the Artist

Abundance and Lack

Commentary by Sara Schumacher

California-based sculptor Lynn Aldrich is known for taking common objects and repurposing them to create sculptures that encourage one to look at those objects in a new and different way.

Bread Line (1991) is a thirty-five-foot installation of freshly baked loaves, sliced up and arranged on the gallery floor in a straight line. The work requires one to walk around or to step over the line while, at the same time, the smell overwhelms one’s senses. The work’s title evokes both a literal queue of people waiting for free or subsidized food and the condition of extreme economic hardship that makes such queues necessary.

On one level, this installation continues the advocacy of postwar artists such as the photographer Dorothea Lange (1895–1965) who used images to highlight the effects of poverty, to bring attention to homelessness, and to generate charity and empathy within those who had the capacity to help. Interpreted within this visual tradition, Bread Line holds in tension themes of plenty and want, abundance and lack. To represent the colloquialism literally is to present us with an irony: the thing so desired (bread) has been used abundantly to represent those who are in need. For bread to be used in this way, excess is necessary.

This same tension between abundance and lack in relation to bread is present in Deuteronomy 8. In the wilderness, the Israelites lacked and were provided with the ‘gift-bread’ of God. Manna, in its daily provision, was a constant reminder of utter dependence (v.16). As the Israelites move into ‘a land where [they] may eat bread without scarcity’ (v.9 NRSV), they are instructed in the right response in order not to forget the Giver of bread. After you ‘eat your fill’, they are told, then ‘bless the Lord your God for the good land that he has given you’ (v.10 NRSV).

Put another way, worship guards against the amnesia that can follow satiation.

References

Brueggemann, Walter. 2001. Deuteronomy (Nashville: Abingdon Press)

Dyrness, William A. 2001. Visual Faith: Art, Theology and Worship in Dialogue (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic)

Lynn Aldrich: Uncommon Artist, dir. by John Schmidt (Biola University, 2016) <https://vimeo.com/135776541> [accessed 30 March 2020]

Pizer, Donald. 2007. ‘The Bread Line: An American Icon of Hard Times’, Studies in American Naturalism, 2.2: 103–28

Frederic Edwin Church

Twilight in the Wilderness, 1860, Oil on canvas, 101.6 x 162.6 cm, The Cleveland Museum of Art; Mr. and Mrs. William H. Marlatt Fund, 1965.233, www.clevelandart.org

The Complexity of Land

Commentary by Sara Schumacher

Here Frederic Edwin Church presents the viewer with a beautiful sunset over an expansive landscape. The bird perched on a branch at the centre left of the composition, directs the eye into dramatic recessions of space, from the broken tree in the foreground, to a river and forest in the middle distance, and then further to a far-off mountain range.

Working within the tradition of the Hudson River School, considered by some to be the first ‘truly American … school of painting’ that was undergirded by ‘a belief in natural religion’ (O’Toole 2005: 11), Church saw symbols of God’s presence embedded in the natural world, meaning his work often takes an allegorical tone. Further, the allegorical potential was heightened by the belief that the expansive and ‘pure’ nature being ‘discovered’ by European settlers was a gift from God.

The title of the work, in addition to describing this American landscape, seems also to evoke the wilderness through which the Israelites wandered. From this vantage point, the viewer joins the Israelites and stands in the liminality of Deuteronomy 8. If the painting helps us imagine what it was like for the Israelites to glance back at the wilderness that had been their ‘home’ for forty years, the setting sun visually reinforces a sense of ‘crossing over’: the closure of one chapter in preparation for the opening of a new one.

However, there is a complexity in how Church depicts humanity’s relationship to the land. There is no human presence in the landscape and the fallen trees and rocky outcrop in the foreground indicate impassability for the explorer, interpreted by some as representing Church’s anxiety about the impact of American over-expansion on nature’s purity (Wilton & Barringer 2002: 129).

This same complexity is evident in Deuteronomy 8. While land is a source of God’s provision (vv.7–9), it is also a means of discipline for unfaithfulness to God (vv.2–5). As the Israelites occupy the Promised Land, they sustain the covenant with God by remembering the wilderness. Conversely, they destroy the covenant by forgetting God’s provision, and are, in turn, destroyed (vv.19–20), ultimately losing the land.

References

Brueggemann, Walter. 1978. The Land: Place as Gift, Promise and Challenge in Biblical Faith (SPCK: London)

Hansen O’Toole, Judith. 2005. Different Views in Hudson River School Painting (New York: Columbia University Press)

Howat, John K. 2005. Frederic Church (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Wilton, Andrew and Tim Barringer. 2002. American Sublime: Landscape Painting in the United States 1820–1880 (London: Tate Publishing)

Eliezer Weishoff

The Seven Species Menorah, 1998, Bronze and olive wood; Gift from the Jewish National Fund in honor of the Knesset's 50th Anniversary, 1998, © Eliezer Weishoff; Photo: Itzhak Harari, Courtesy the Knesset Archives

The Provision of the Land

Commentary by Sara Schumacher

Within the Jewish tradition, the menorah is both religious object and secular symbol. The menorah, a seven branched golden lampstand, was present in Herod’s Temple in Jerusalem and captured by the Romans at its fall in 70 CE, an event depicted on the Arch of Titus in the Roman Forum. This depiction initially turned the menorah into a symbol of humiliation for the Jewish people.

As time progressed, symbolic connotations shifted, and images and replicas of the menorah became eschatological symbols of hope for the restoration of the land and the coming of the Messiah. Particularly with the establishment of Israel as a nation-state, the menorah is now a national, secular symbol of actual territory and of national rebirth, seen most explicitly in its inclusion on the seal of Israel.

Eliezer Weishoff’s Seven Species Menorah (1999)—a gift by the Jewish National Fund to celebrate the fiftieth birthday of the Knesset (Israel’s parliament) and located within its building—sits within the tradition of menorah as national symbol. The symbolism is furthered by the way that Weishoff depicts his menorah. First, the seven ‘lamps’ are placed so that they appear to grow out of the trunk of an actual olive tree, symbolizing Israel’s deep historical roots in a particular land as well as ‘the renewed growth of the people of Israel in their land’ (Rolef n.d.). The particularity of his adaptation of the menorah symbol is furthered in how Weishoff depicts, instead of lamps, the seven species listed in Deuteronomy 8:8—figs, grapes, dates, pomegranates, wheat, barley, and olives—at the head of the seven branches.

In Deuteronomy 8, the list of the seven species points forward to the abundance of the Promised Land. Rather than God’s provision of daily manna in the wilderness, God enables the land to provide for His people. Thus, by representing these seven species in his work, one could suggest Weishoff’s menorah visually claims the same abundant provision and blessing of God for the nation-state of Israel.

References

Fine, Steven. 2016. The Menorah: From the Bible to Modern Israel (Cambridge: Harvard University Press)

Israeli, Yael. 1999. In the Light of the Menorah: Story of a Symbol (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum)

Rolef, Susan Hattis. n.d. Artwork in the Knesset <https://knesset.gov.il/birthday/eng/KnessetBuilding2_eng.htm> [accessed 30 March 2020]

Lynn Aldrich :

Bread Line, 1991 , Bread

Frederic Edwin Church :

Twilight in the Wilderness, 1860 , Oil on canvas

Eliezer Weishoff :

The Seven Species Menorah, 1998 , Bronze and olive wood

Remembering We Are Creatures

Comparative commentary by Sara Schumacher

In Deuteronomy 8, the Israelites are at the boundary of the Promised Land. The forty years of wandering in the wilderness have come to an end, and they are about to become a landed people.

At this juncture, Moses gives them two commands: to remember and not to forget. For both commands, the land plays a central role in aiding obedience. The Israelites are to remember how God provided for all their needs in a wilderness that could not provide for them. As they move into an abundant land that can, they are commanded not to forget God in their satiation.

The artworks chosen for this exhibition are intended to bring into sharp relief how land and its produce are conduits for acts of remembering and not forgetting. However, the works open up new ways in which the text continues to help us not to forget who we are. When we remember that we are creatures, we do not forget God as Creator. Conversely, when we remember that God is Creator, we do not forget that we are creatures.

While Bread Line remembers abundance and does not forget those who are in want, it also points to humanity’s mandate to cultivate creation. Lynn Aldrich has taken what another made and, in placing it in a gallery space, has turned it into something else. She has seen bread to be more than food and, through her work, so do we. Even after we see her work, bread is never the same if we choose to allow it to be an object of remembrance. When we see, taste, touch, and smell, we are reminded that ‘we participate in a grace-saturated world, a blessed creation worthy of attention, care, and celebration’ (Wirzba 2001: 2).

This creaturely mandate to cultivation is also present in Deuteronomy 8. The Promised Land is described as ‘a land with wheat … where you may eat bread without scarcity’ (vv.8–9). Of course, for ‘wheat’ to become ‘bread’, humans must work with the material object to create something new. While the wilderness was a place where bread came as direct provision from God and thus was a daily reminder of utter dependence (v.3), in the Promised Land, one might suggest the act of cultivation stands in as the site of remembrance. As one makes bread, one remembers that it is God who gives the wheat. As recipients of this generosity, the only proper response is worship. One can read this same dynamic in another site of active remembrance: the Christian Eucharist. In words reminiscent of Deuteronomy 8, the eucharistic liturgy guides those assembled to pray:

Blessed are you, Lord God of all creation: through your goodness we have this bread to set before you, which earth has given and human hands have made.

While God promises to provide through the land, when one possesses the land and is faced with its uncontrollability, one’s creatureliness becomes acute. In the period it was made and influenced by Romanticism, Twilight in the Wilderness was a deliberate evocation of the divine through landscape. While nature acted as a conduit to communing with God, the sublimity of nature, the response of terror in being overawed by the spectacle, was a further reminder not only of humanity as creature but also of God as Creator. The sublimity of nature shocks us out of our autonomy, reminding us that we are not in control, moving us to worship of the One who is. Twilight reminds us that, while ever-changing, humanity is never not in relationship with nature. When we think we are its master, its sublimity brings us back to a place of dependence upon and submission to the Creator of all things.

The Seven Species Menorah, while making a political statement about the rebirth of Israel as a modern nation-state, is also a marker of human identity in relation to God. The imperatives in Deuteronomy 8 indicate the kind of people the Israelites are about to become: from wanderers in the wilderness to a settled people. However, this ‘somewhere’ is a covenanted land, meaning that quality of life in the land is dependent on Israel’s faithfulness to the covenant (vv.19–20). God, in his grace, has embedded reminders to faithful living in the produce of the land, reminders which persist in how the seven species have now become foundational to the region’s cuisine. As seen already in Bread Line, to cultivate the natural world and make food for the table from which we are nourished has the capacity to be an ongoing reminder of God’s provision. Within Judaism, this is further reinforced by the status given to the seven species in Jewish law, the special blessing said after eating, and their contribution to the festivals of Tu Bishvat, Sukkot, and Shavuot.

With Bread Line and Twilight, Eliezer Weishoff’s Menorah hints at the sacramental potential of the natural world to point to a deeper meaning: creation and its creatures are sustained by a Creator worthy of worship, praise, and obedience. Conversely, to forget is destruction—for the world, the other, and the self.

References

Brueggemann, Walter. 2001. Deuteronomy (Abingdon Press: Nashville)

_______. 1978. The Land: Place as Gift, Promise and Challenge in Biblical Faith (London: SPCK)

Wilton, Andrew and Tim Barringer. 2002. American Sublime: Landscape Painting in the United States 1820–1880 (London: Tate Publishing)

Wirzba, Norman. 2011. Food and Faith: A Theology of Eating (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Commentaries by Sara Schumacher