James 4:13–5:6

Rotten Riches

Banksy

Maid in London (Sweeping It Under the Carpet), 2006, Mural, No longer extant [Chalk Farm, London]; ArtAngel / Alamy Stock Photo

The Politics of Recognition

Commentary by Ruth Jackson Ravenscroft and Simon Ravenscroft

James 5:4–6 highlights the economic injustices on the back of which the prideful rich, condemned in the preceding lines, have accumulated their wealth: ‘Behold, the wages of the labourers who mowed your fields, which you kept back by fraud, cry out’. Justice and righteousness are often associated in Scripture with the recognition and defence of the materially poor. Those whose voices go unheard by the representatives of political and economic power ‘[reach] the ears of the Lord of hosts’.

Historically, the production of art was linked closely with the rich and powerful, who had the funds to make commissions; and yet many artists chose nevertheless to depict the lives of the poor in their work. Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Harvesters (1565), Diego Velázquez’s The Waterseller of Seville (1618–22), and Vincent van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters (1885) all spring to mind. Depicting the poor does not, of course, necessarily mean fighting for them: under the sentimentalizing gaze of the rich, their lives can become quaint decoration for the walls of large houses. But today, the street artist Banksy is a pre-eminent artist not only of but also for the poor.

Sweeping it Under the Carpet is explicitly about democratizing not just the locations but also the subjects of artworks, about giving recognition to those who do not usually receive it, who labour under unfair and unequal systems—echoing the passage from James. Banksy has commented, ‘In the bad old days, it was only popes and princes who had the money to pay for their portraits to be painted. This is a portrait of a maid called Leanne who cleaned my room in a Los Angeles motel’ (Bull 2011: S20).

A melancholy but politically meaningful irony is that Leanne’s recognition would only be temporary. Two versions were painted in London: one in Chalk Farm on the wall of a performance venue (shown here), one in Hoxton on the exterior of a commercial gallery. Both have since been painted over. Banksy’s medium is part of his message in this sense. By showing Leanne about to hide her sweepings under a carpet, the work suggests how the wealthy and powerful sweep issues of social injustice and inequality ‘under the rug’, in the very way his street art, which highlights these issues, gets painted over.

References

Bull, Martin. 2011. Banksy Locations and Tours Volume 1: A Collection of Graffiti Locations and Photographs in London, England (Oakland: PM Press)

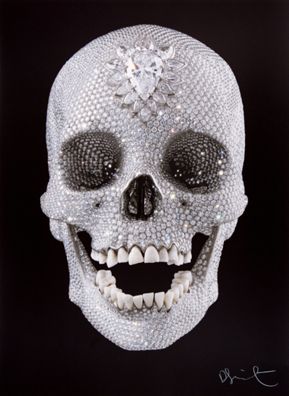

Damien Hirst

For the Love of God, 2007, Platinum, diamonds, and human teeth, 17.1 x 12.7 x 19 cm, Location unknown; © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved DACS / Artimage, London and ARS, NY 2018. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

Death and Investment

Commentary by Ruth Jackson Ravenscroft and Simon Ravenscroft

In 2007, Damien Hirst set 8,601 pavé diamonds weighing 1,106.18 carats into a platinum cast of a human skull dated to 1720–1810, acquired from a London taxidermist (the work incorporates the original teeth). The result—entitled For the Love of God—is a work of startling, indeed sparkling, ambiguity.

Positioning itself in a long tradition of memento mori artworks, this sculpture serves as a reminder of the transience of life and the mortality of the viewer. Yet it is also made from materials of extreme durability. The letter of James says to the rich, ‘your riches have rotted … your gold and silver have rusted’ (vv.2–3), but Hirst’s platinum and diamond skull is exceptionally resistant to decay. Does it thus achieve a kind of victory over death? Platinum and diamonds are also highly valuable. For this reason the diamond trade has its own special association with violence and death. Is the work a celebration or denigration of wealth? Does it signal the sublimity or the emptiness of earthly riches?

Hirst has said of death, ‘You don’t like it, so you disguise it or you decorate it to make it look like something bearable—to such an extent that it becomes something else’ (Hirst in Burn 2008: 21). But death is relentless, even when hidden beneath a mask of diamonds.

There is a layer of religious ambiguity in the work’s title. ‘For the love of God’ is an expression of exasperation—it has the air of mild blasphemy. But it is an invocation of the divine all the same. Maybe even a prayer.

The deceitfulness of wealth is a regular theme in Scripture. Like Hirst’s diamond skull, the passage from James calls attention to the emptiness of earthly riches in light of the transience of life. Both the biblical text and the sculpture ask where true wealth is found, whether in spiritual or material goods, and by extension, where we should invest our time, attention, and devotion while we live and breathe.

References

Burn, Gordon. 2008. ‘Conversation’ in Beautiful Inside My Head Forever Sotheby's 15 and 16 September 2008, vol. 1 (London: Sotheby’s)

Hans Holbein the Younger

Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve ('The Ambassadors'), 1533, Oil on panel, 207 x 209.5 cm, The National Gallery, London; Bought 1890, NG1314, © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

Beauty and Decay

Commentary by Ruth Jackson Ravenscroft and Simon Ravenscroft

Hans Holbein the Younger’s painting depicts in delicious detail Jean de Dinteville (on the left), French ambassador to the court of King Henry VIII, and his friend George de Selve (on the right), the young Bishop of Lavaur. The men are clad in sumptuous robes, and stationed either side of two shelves laden with myriad curious instruments, musical and astronomical. In the foreground, a distorted (anamorphic) image of a skull can be identified if viewed from a point to the right of the picture (from which vantage point the distortion is corrected). A silver crucifix is just visible, emerging from the curtain in the top left corner.

Commissioned at great cost and exactingly made, the picture situates its two subjects within the slow march of time and decay—within a world where humans scramble for knowledge, peace, and order, while knowing death and salvation to be outside their own control.

The letter of James announces to men in the business of trade and travel, that ‘you do not know about tomorrow’ (James 5:14). Everything is subject to the will of the Lord; to boast in one’s plans is futile.

At first glance, the proliferation of instruments in the painting (a celestial globe, a portable sundial, and various other instruments used for understanding the heavens) might speak to the ambassadors’ confident pursuit of control, since these devices indicate practices of measuring and navigating the earth, and of calculating the time. Yet this impression is dislodged by the Lutheran hymnal on the bottom shelf, which evokes the unwieldy religious conflict preoccupying these Christian men in 1533, in the advent of Henry VIII’s break with Rome (Foister et al. 1997: 40). Their apparent confidence is also undermined by the distorted human skull in the foreground of the work, which—unlike the beautiful and richly detailed objects above and around it—is not so easily grasped and enjoyed by the human senses.

By thus relativizing what is material and temporal while reminding us of death, this strange skull, slipping in and out of focus, provokes the question in the passage from James 4:14: ‘What is your life? For you are a mist that appears for a little time and then vanishes’.

References

Berger, John et al. 1972. Ways of Seeing (London: BBC)

Foister, Susan, Ashok Roy, and Martin Wyld. 1997. Making and Meaning: Holbein's Ambassadors (London: National Gallery London)

Banksy :

Maid in London (Sweeping It Under the Carpet), 2006 , Mural

Damien Hirst :

For the Love of God, 2007 , Platinum, diamonds, and human teeth

Hans Holbein the Younger :

Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve ('The Ambassadors'), 1533 , Oil on panel

Dispossessed Life

Comparative commentary by Ruth Jackson Ravenscroft and Simon Ravenscroft

At the end of James 4 we read: ‘Whoever knows what is right to do and fails to do it, for him it is sin’ (v.17).

The active ignorance described here—working against truth and justice in full knowledge of what is right—is in the context of the whole passage revealed as a sinful symptom of human pride. James targets those who speak with certainty about their future plans, as if they were unquestionably achievable. These people have forgotten their finitude, ignoring how it is only by the will of God that they live, or do this or that. Arrogance has led them to deny their limitations and that their existence is given them from without. They have, in idolatrous defiance of the eternal, made gods of themselves.

There are myriad memento mori paintings hanging in the world’s art galleries which signal the vanity and futility of human plans by featuring a skull prominently among other worn-out objects—bottles, candles, well-thumbed books. The skulls in these pictures disclose the inevitability and routine quality of death; like the flow of time and the process of ageing, death qualifies life and should not be ignored. The works by Hans Holbein the Younger and Damien Hirst featured here push beyond this simple, forlorn note about the mundane nature of death, but in divergent ways.

The distorted skull in Holbein’s painting of the French ambassadors is at once prominent and difficult to discern. Death is made central to the double portrait of these men, but it slips in sideways, in an out-of-the-ordinary way. We must watch for it carefully. Recognizing life’s limits means cultivating our powers of attention.

By contrast with this obliqueness, but just as out-of-the-ordinary, Hirst’s skull announces itself with brilliant light bouncing off its copious diamonds. Gemstones line even its open eye sockets and nasal cavities. The skull becomes more than a reminder of a once-living creature. Its jaw may be full of human teeth, but the face has become an inhuman, sparkling mask, which grins a fixed and unnatural smile. Death in this imagining is hypostasized, made concrete. It screams out at us, sublime and triumphant—coming at us as if from outside the flow of time. How can we ignore it?

If death here seems to take the form of a richly decorated idol, then perhaps Hirst’s work also plays on the ways our world has made death ultimate. Treating this life as all there is, we fear death as the moment when all is lost, and so expend our wealth (through medical science) in delaying death’s arrival for as long as possible—a kind of propitiation, for the love of this false god?

James 5 addresses the wealthy. We are told that the rich have taken what is not theirs to take, and are given a vivid image: the unpaid wages of labourers ‘cry out’ (v.4) as if from the very pockets of fraudulent employers. Profit gained through oppression and dishonesty, these unpaid wages witness, wailing, to their misappropriation.

The works by Banksy and Holbein meet this theme of unworthy consumption and unjust possession from sharply contrasting perspectives. Banksy’s graffiti, executed illegally on external, publicly visible walls cannot by design be valued or possessed in the same manner as Holbein’s painting, which was commissioned at great expense for Jean de Dinteville’s residence in Polisy. Banksy creatively appropriates surfaces which are already visible in public spaces, to draw attention to matters of shared concern—injustice and inequality. He trespasses on the customary uses of buildings (in this case, a performance space and a commercial art gallery) and gives them a renewed political meaning for passers-by. Sweeping it Under the Carpet prompts us to think critically about the proper relationship between ownership and enjoyment in our world.

The politics of possession are also evoked by the objects represented in Holbein’s work. The distorted skull in the foreground derives its eeriness in part from its juxtaposition with the ornate and rich objects above it which—unlike the skull—are eminently visible and ownable, many of them instruments for aiding human conquest and control. By thus evoking the frailty of material life in time, Holbein’s painting, despite being an expensive private commission replete with variously lavish and sophisticated objects, relativizes the supposed virtues of ownership and possession, just as Banksy’s does by disrupting private property claims over artworks and external walls.

Possessions are not sources of ultimate value, security, or joy. Living as if they are—accumulating pridefully, unjustly, in a way that harms others—is misdirected and futile, as the book of James maintains.

References

Fuchs, Rudi. 2008. ‘Victory over Decay’ in Damien Hirst: Beyond Belief (London: Other Criteria/White Cube)

Rowlands, John. 1985. Holbein: The Paintings of Hans Holbein the Younger (Oxford: Phaidon Press)

Commentaries by Ruth Jackson Ravenscroft and Simon Ravenscroft